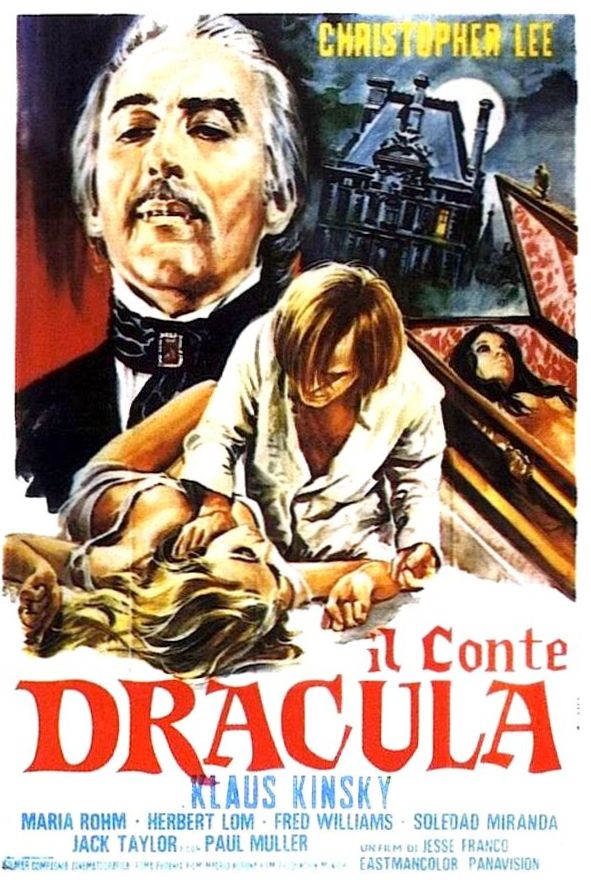

Star: Christopher Lee, Herbert Lom, Soledad Miranda, Klaus Kinski

Dir: Jess Franco

While I appreciate the idea of making a more faithful adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel, going back in many ways to its original roots, I’m not sure getting Jess Franco to direct it was the smartest idea. Whatever his merits, he was hardly known for PG-rated works inspired by Victorian literature, and despite a couple of bits of impressive casting, in Lee and Kinski, this feels about 15 years too late, and a bland supporting cast leave it marooned in, at best, the middle tier of vampire movies.

The main coup is, of course, getting Lee to reprise his most famous role, even if this was the third chance to sink his fangs into Count Dracula that year, its release (at least, in Germany) just managing to pip Taste the Blood of Dracula to cinemas, and with Scars of Dracula following later. [Blood wasn’t even supposed to include the Count at all, but the US distributor balked, and he was talked into playing the role again; Lee later complained Hammer’s president used “emotional blackmail” to convince him to keep playing Dracula, saying the crew would be put out of work otherwise – I wonder if it was for this film?]. He was growing increasingly disenchanted with the direction Hammer were taking: “They gave me nothing to do! I pleaded with Hammer to let me use some of the lines that Bram Stoker had written. Occasionally, I sneaked one in.” Here, no such sneaking was needed, and indeed, the film’s best scene has the Count delivering a sonorous monologue about his ancestors, which is close to Stoker’s text:

“To us was entrusted for centuries the guarding of our lands. The Lombard, the Bulgar, the Turk, poured their thousands against our frontiers – we drove them back! The Draculas have ever been the heart’s blood, the brains, the sword of our people. One of my race crossed the Danube and destroyed the Turkish host. Though sometimes beaten back, he came again and again against the enemy, till at the end, he came alone from the bloody field, for he alone could triumph. THIS was a Dracula indeed!”

Another cool aspect is the way this Count starts off as old, and gradually becomes more youthful and active as the film goes on and he quenches his thirst on more victims – something also used in Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. But the film still takes liberties with the text, some of which don’t work, such as the way Jonathan Harker escapes Dracula’s castle, and is transported back to Great Britain, to rehab in a facility – here run by Professor Van Helsing (Lom) – which directly overlooks… Dracula’s English mansion. Really, what are the odds? The fiance of Lucy Westenra (Miranda) is now Quincy Morris, with Arthur Holmwood entirely omitted. So, while more faithful than many, it’s clear the makers still felt it necessary to make a number of concessions on the transition from page to screen.

Another cool aspect is the way this Count starts off as old, and gradually becomes more youthful and active as the film goes on and he quenches his thirst on more victims – something also used in Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. But the film still takes liberties with the text, some of which don’t work, such as the way Jonathan Harker escapes Dracula’s castle, and is transported back to Great Britain, to rehab in a facility – here run by Professor Van Helsing (Lom) – which directly overlooks… Dracula’s English mansion. Really, what are the odds? The fiance of Lucy Westenra (Miranda) is now Quincy Morris, with Arthur Holmwood entirely omitted. So, while more faithful than many, it’s clear the makers still felt it necessary to make a number of concessions on the transition from page to screen.

Klaus Kinski plays Renfield, in a casting choice of both staggering obviousness and brilliance, matched only by Kinski’s other collaborations with Franco, where he played Jack the Ripper and the Marquis de Sade. In this case, it’s a virtually non-verbal performance, where his sole line is “Varna…”, uttered just before Renfield shuffles off this mortal coil, to tell the good guys where the Count is heading. But that doesn’t make it any less memorable, since Kinski has always been capable of conveying an entire chapter of emotion with a stare, and is allowed to do so freely in this film. Right from the first time we see him, hurling food about his cell, it’s clear that this Renfield is barking mad – and that’s before he starts chowing down on his favorite snack, dead flies, which he has hidden in a box in his cell. According to Jay Marks and Waylon Wahl, Kinski took Franco to task for not filming Renfield’s scenes in an actual asylum, to which the director responded, “I had planned to shoot it in a real cell but then it occurred to me that they might not let you out!”

Certainly, it’s fair to say that, as well as the canonical Dracula, in Kinski this film also has the canonical Renfield, and I don’t think anyone can match the intense lunacy of his portrayal. Where the film goes off the rails is with the good guys in the cast, starting with Lom as Van Helsing, who is a very pale shadow indeed of, say, Peter Cushing. And that’s before he inexplicably appears to suffer a stroke, which confines him to a wheelchair for the rest of the movie (perhaps inspiring Dr. Everett Scott in The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which hit the stage three years later?). The rest of the cast are equally forgettable, despite the scenic contributions of Miranda, and Maria Rohm as Mina – although the latter remain far more clothed than most Franco ladies! And, indeed, Hammer ones of the time, as they released The Vampire Lovers the same year, the first of their Karnstein trilogy.

That’s perhaps what I mean about it being 15 years too late. In tone and content, this comes across as less daring than even Blood of Dracula, made in 1957 and whose success led directly to the entire “Hammer Horror” filmography which followed. That packed much more of a wallop than this even lower-rent version does, which has all the impact of the giant polystyrene rocks used to disrupt the Count’s escape at the end [you can clearly see one of them glancing off the side of a horse’s head as they are “hurled” down from a nearby cliff. And do not even get me started on the “bat” effects…]. The truth is, for all the influence Dracula had, Stoker isn’t actually all that good a writer – if you can name two of his 11 other novels, it will be one more than I can manage, and my Lair of the White Worm knowledge is entirely through Ken Russell’s adaptation. So a faithful translation to the screen may seem like a good idea in theory, yet it tends to bring over as many negatives as pluses. This film demonstrates why most movie versions have tended to take only the core, and leave everything else.