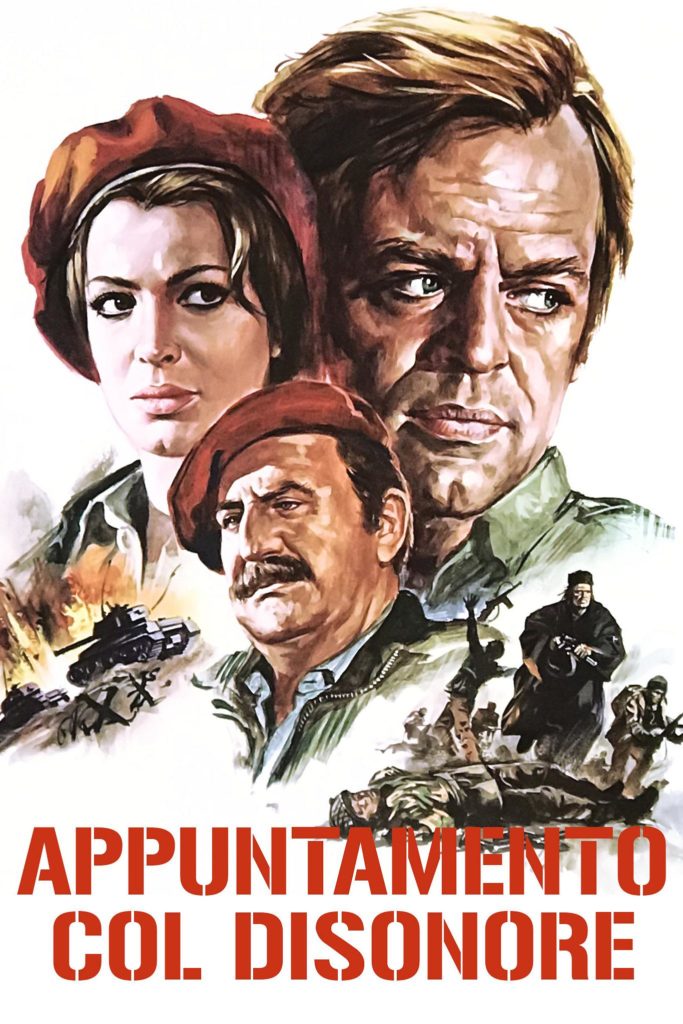

Dir: Adriano Bolzoni (as William McCahon)

Star: Michael Craig, Eva Renzi, Adolfo Celi, Klaus Kinski

a.k.a. The Night of the Assassin

This certainly shines a bit of light on an area of European post-way history with which I was not very familiar. So let’s begin with a Cliff Notes discussion of Cyprus and its struggles for independence from the British Empire. Britain had offered Cyprus to Greece during World War I, if they entered the conflict on its side. The offer was declined, but through the end of World War II, the Greek Cypriot population continued to hope for enosis – a term that crops up frequently in the film, meaning (in the specific case of the island) a re-unification with Greece. However, the significant Turkish Cypriot population had no interest in this, and wanted the island instead to be divided into Greek and Turkish areas.

In 1955, a group called EOKA (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston).began a campaign against the British colonial powers, including bombings, attacks on police stations and UK forces, and against those Cypriots seen as collaborators. That’s more or less the period where the film joins proceedings. In the interest of completeness, I’ll tell you now that Cyprus became an independent state in 1960, though was hardly the end of the problems. Greece carried out a coup d’etat in 1974, which was followed five days later by Turkey invading and occupying the northern part of the island. That’s more or less where it stands today, though relations between the two communities have become more cordial of late.

Ok, so now you’re up to speed. The film starts with the arrival in Cyprus of Col. Stephen Mallory (Craig), a British officer who is tasked with keeping the peace in the troubled community. Virtually before he has unpacked, he’s embroiled in a potential crisis, when a young local boy steals a soldier’s gun and holes up in a well. After initially wanting to solve the problem with a grenade (!), Mallory thinks better of it, and takes the boy into custody. It’s to the mixed relief and anger of his mother, Helena (Renzi); but helped by Mallory arranging for the release of her son on parole, the two begin a relationship. This is a bit awkward, as she also has ties to EOKA. They want her to pump him for useful information; he is also keen to use her as a conduit to speak with its leader, Hermes (Celi), to agree to a ceasefire and peace talks.

Negotiations are of particular importance, as the Secretary-General of the United Nations is about to pay a visit to Cyprus, and could provide a breakthrough towards a negotiated settlement. However, not everyone is keen on the idea, notably Hermes’s second-in-command, the priest Evagoras (Kinski). The involvement of clergy in terrorism perhaps isn’t as far-fetched as it might seem. The first president of independent Cyprus was Archbishop Makarios, who certainly knew the leader of EOKA and had common goals with it, though the extent of his ties is uncertain. Evagoras doesn’t want peace on these terms, being engaged in negotiations of his own, and prepares a “false flag” attack on the Secretary-General, to be blamed on pro-British Cypriots. To that end, he kidnaps Mallory and Hermes when they are meeting, aiming to force Mallory into signing a “confession” for the attack. They need to escape and stop it from taking place.

I found the movie surprisingly decent, being more nuanced than I expected. All the various factions – Greek, Turkish and British – are presented with some degree of sympathy, and it’s made clear that none have a monopoly on good or evil. That is present at a personal level, e.g. Hermes vs. Evagoras, with the former being far more open to peace through negotiation, while the latter believes it can only be achieved by direct action, and will accept no compromise in this area. Helena, in particular, is caught in the middle, finding herself torn between what’s best for herself, best for her son, and best for her country. It’s a decision which may end up being mutually exclusive, forcing her to decide which loyalties are the most important. Bolzoni, best known as one of the writers on A Fistful of Dollars, does a good job of weaving a story out of the multiple threads, in a way that keeps the viewer interested. At least, for the majority of the film’s running-time.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t quite sustain this success to the end. The escape of our heroes from Evagoras’s underground lair is overlong, and degenerates into little more than lengthy bursts of automatic weapons, from one poorly-lit corner to another. What had gone before deserves a considerably better finale, even if the exploding boat is impressive (Bolzoni seems to have liked it too, going by the variety of angles from which we see the giant fireball!). As for Kinski’s role, it does come as a shock to see him sporting Greek Orthodox robes, with a large crucifix dangling in front. I kept wondering if he was going to all Jesus Christus Erlöser on us. Once it becomes clear this is not a “turn the other cheek” type of priest, however, you can settle down and enjoy Klaus’s performance, as part of a surprisingly decent thriller.

In a 2005 interview, co-star Renzi talked about her experience with Kinski. She wasn’t exactly complimentary, basically starting off by saying “He was a psychopath. He was a madman”, though in almost the next breath grudgingly admits, “He had a magnetism, there’s no doubt about it, he was very interesting in his mannerisms.” As for their relationship during filming, she said “I thought he was very, very unpleasant as a partner, very egomaniac[al].” She goes on to say that Klaus “blew himself up” in an unsympathetic way, and describes him “arriving in Yugoslavia [where I presume this was filmed] with twenty-five pieces of luggage and a Bentley.” She ends that section of the interview by making what can only be described as a retching sound!