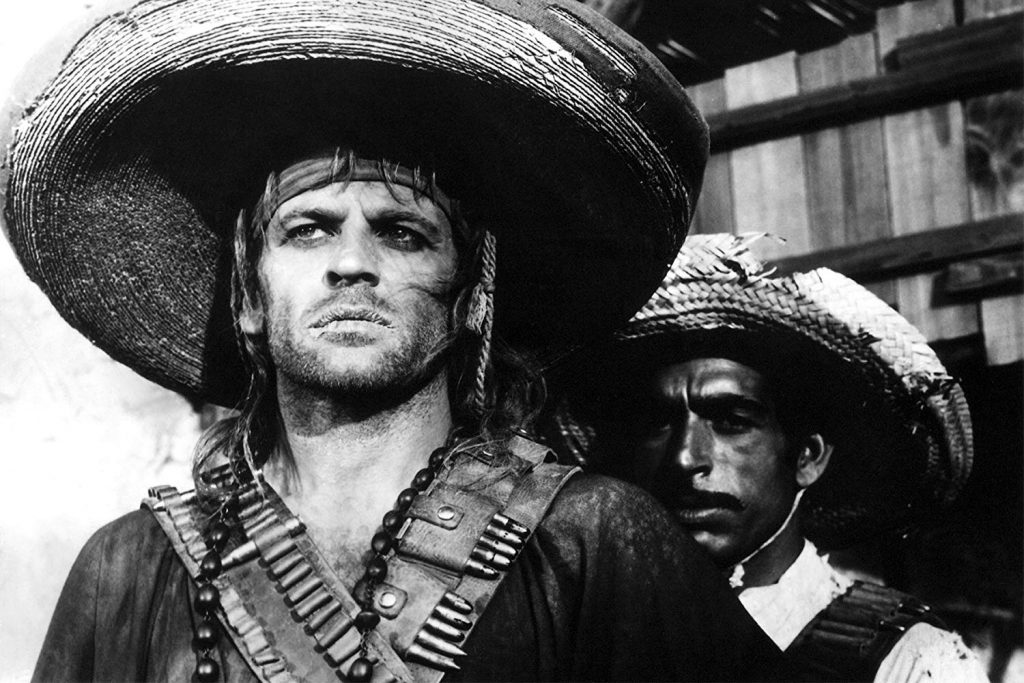

Dir: Damiano Damiani

Star: Gian Maria Volonté, Lou Castel, Klaus Kinski, Martine Beswick

a.k.a. El Chucho Quién Sabe?

Likely regarded as one of the top tier of spaghetti Westerns – at least, outside those directed by Sergio Leone – this founded the genre of ‘Zapata Westerns’. Wikipedia defines these as featuring a variant of the hero pair with “a revolutionary Mexican bandit and a mostly money-oriented American from the United States frontier.” Certainly, this is considerably more overtly political than most others in Kinski’s filmography, being set in the Mexican Revolution. This took place in the nineteen-tens, beginning as a revolt against the established order, but ending in a messy, multi-factioned civil war, and resulting in the death of more than a million Mexicans overall.

It’s clearly well under way when we join the action, a government train coming under attack from rebel forces under El Chuncho (Volonté), seeking to “liberate” the weapons it is carrying. Their raid eventually succeeds, thanks largely to help from an American passenger, Bill Tate (Castel), who joins the rebel gang. El Chuncho is less a philosophical rebel than a mercenary one, and intends to sell the arms to the leader of the rebels, General Elias. But there’s work to be done before that, such as pursuing Chuncho’s “white whale”, a legendary golden machine gun. It’s also clear from early on that Tate, nicknamed Niño by the gang for his boyish good looks, has an agenda of his own, and also has a love-hate relationship with gang moll Adelita (Beswick).

Right from the beginning, the harsh nature of the war is made clear: the first scene shows a firing squad executing rebels. Then the train is stopped by El Chuncho placing ahead of it, a captured Mexican officer, who has been crucified on the tracks. Still alive, the only way for the train to get out of the rebels’ “kill box” is to drive over the prisoner. This sets the tone for a film which is generally brutal in tone, with Damiani pulling no punches about the selfish nature of many of those involved, on both sides. The key point on which the film hangs is El Chuncho’s decision to leave the town of San Miguel. He and his gang have already overthrown the town’s leader, Don Felipe, executing him. But he and the bulk of his gang then leave the town, taking all the weapons with them to sell to Elias – and leaving San Miguel wide open to government reprisal. When the inevitable happens, El Chuncho feels personally guilty.

Kinski’s role here is as El Chuncho’s sibling, a man of God known as El Santo. There’s almost some foreshadowing of Jesus Christus Erlöser, filmed five years later. When El Santo is asked by another priest why he is living with thieves, he spits back, “Christ died between two thieves! God is with the poor and the oppressed. If you’re a good priest, you should know that.” A subsequent rant causes Tate to ask El Chuncho, “Is he mad?”, to which the response is a shrug and “He’s my brother.” Half-brother, to be exact: “Same mother, and the father, who knows?” But Santo doesn’t realize that Chuncho is in the arms business, thinking the weapons are donated to Elias “for the triumph of the revolution.”

SPOILERS. It’s this deceit which eventually proves his downfall. When El Chuncho delivers his arms to Elias, he discovers his greed led to the defenseless inhabitants of San Miguel being slaughtered. He accepts execution as his fate, only for El Santo to pop up – apparently the sole survivor – and demands the right to carry out the punishment: “He’s my brother. My blood.” When Chucho remind his brother he had said that God is good and generous, we get one of the classic Kinski lines: “God is. But I’m not…” And neither is Tate. For having carried out what has been his mission all along – the assassination of Elias – the American then saves Chucho by shooting his brother, as the priest is about to execute him.

That alone would be a wonderfully bleak way to end a movie. But, wait! There’s more! For Chuncho tracks down Tate, who has just received his 100,000 pesos bounty from the government, with the aim of killing him. But Tate shows that he had left behind half the bounty for Chuncho, in thanks for the (unwitting) help, and the two men agree to return to America and begin a new life. But when Chuncho discovers everything had been a set-up from the train robbery in the beginning, he has a further change of mind and announces he must kill Tate. The American asks why to which El Chuncho replies, “¿Quién sabe?” [Who knows?] before gunning the assassin down. END SPOILERS.

Damn. That’s some cynical cinema. Damiani makes it clear his sympathies are with the rebels – as you’d expect, considering the film is generally considered to have been written by Franco Solinas, who was also responsible for The Battle of Algiers. Yet there’s no black and white to be found here: it’s all shades of murky grayness, such as El Chuncho’s enthusiasm for destroying the old order, even as he lacks anything at all credible with which to replace it. The original plan was to film this in Mexico, but it ended up being Spain as usual.

For Kinski, the highlight is a raid on an army outpost, where El Santo interrupts a medal ceremony: “Don’t pin medals on criminals! They’ve killed children and women. They’ve tortured people. And now your hour is come! The Lord curses you thieves and murderers! I curse all of you, d’you hear me? Assassins of Mexico, I challenge you!” before reciting the Trinitarian formula, punctuating each element by lobbing a hand-grenade at the soldiers. Again, classic Klaus. It’s a large part of the reason why the Village Voice said, “The best reason to see the movie is for Kinski, who delivers the film’s most arresting performance. Coasting on manic charm, Kinski steals every scene he’s in.” Hard to argue with that.

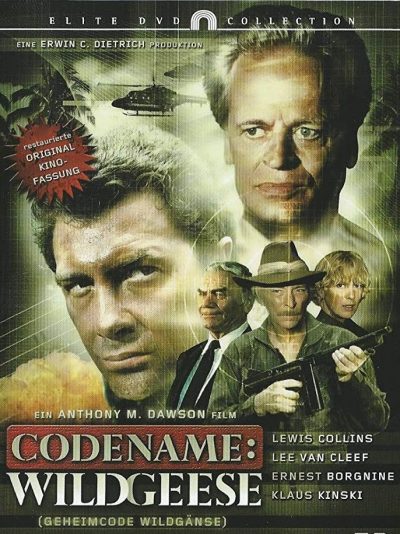

[Spoilers follow] Inevitably, it turns out that some of the people on the outside are working with and for Khan. The shadiest of all is wealthy American businessman Brenner (Hartmut Neugebauer) and his partner, Charlton, who is himself a former soldier for hire. When Wesley opts to continue the mission and moves towards destroying another plant, thereby threatening the pipeline which Brenner uses to get his drugs out, Charlton is sent into the jungle to make sure that the mercenaries do not succeed. With the entire operation being thoroughly off the books, Wesley is on his own to try and ensure that he and his men are not the ones being cleaned up. And he’s not happy about being betrayed either, especially given the whole ‘dead son’ thing. [End spoilers]

[Spoilers follow] Inevitably, it turns out that some of the people on the outside are working with and for Khan. The shadiest of all is wealthy American businessman Brenner (Hartmut Neugebauer) and his partner, Charlton, who is himself a former soldier for hire. When Wesley opts to continue the mission and moves towards destroying another plant, thereby threatening the pipeline which Brenner uses to get his drugs out, Charlton is sent into the jungle to make sure that the mercenaries do not succeed. With the entire operation being thoroughly off the books, Wesley is on his own to try and ensure that he and his men are not the ones being cleaned up. And he’s not happy about being betrayed either, especially given the whole ‘dead son’ thing. [End spoilers]

It’s not long before the chief of security is also a corpse, and West is ordered to take over as his replacement, in order to keep an eye on the leader of Sinonesia, President Boong (Kinski). Which is where his path crosses with the plot of Sumuru (Eaton, famous for being painted to death in Goldfinger), the villain in the piece who is intent on building a world ruled by women. Look, that may seem now like Democratic Party policy (hohoho!). But this was the sixties, and nothing more evil – or, at least, more amusingly evil, at the level appropriate for a tongue in cheek spy flick like this – than a gynocentric society could possibly be imagined for the era. Pat those amusing little ladies on their pert little behinds, and send them back into the kitchen!

It’s not long before the chief of security is also a corpse, and West is ordered to take over as his replacement, in order to keep an eye on the leader of Sinonesia, President Boong (Kinski). Which is where his path crosses with the plot of Sumuru (Eaton, famous for being painted to death in Goldfinger), the villain in the piece who is intent on building a world ruled by women. Look, that may seem now like Democratic Party policy (hohoho!). But this was the sixties, and nothing more evil – or, at least, more amusingly evil, at the level appropriate for a tongue in cheek spy flick like this – than a gynocentric society could possibly be imagined for the era. Pat those amusing little ladies on their pert little behinds, and send them back into the kitchen!

It’s the story of two brothers, Jason (Gemma) and Adam (Kinski), career criminals. Jason carries out a jewel heist, and at Adam’s request, uses the loot as bait to lure in the family’s enemies, so they can be disposed of by Jason. This goes swimmingly, only for Adam to get greedy and also demand a share of the jewels, which Jason feels should be payment for his bloody work. Considering the number of dead bodies he had to go through to keep the ill-gotten gains, I can kinda see his argument. After he refuses to share, Adam goes after Jason and eventually gets him to give up the loot after threatening his girlfriend, Karen (Lee).

It’s the story of two brothers, Jason (Gemma) and Adam (Kinski), career criminals. Jason carries out a jewel heist, and at Adam’s request, uses the loot as bait to lure in the family’s enemies, so they can be disposed of by Jason. This goes swimmingly, only for Adam to get greedy and also demand a share of the jewels, which Jason feels should be payment for his bloody work. Considering the number of dead bodies he had to go through to keep the ill-gotten gains, I can kinda see his argument. After he refuses to share, Adam goes after Jason and eventually gets him to give up the loot after threatening his girlfriend, Karen (Lee).

To mis-quote Mike Tyson, “Everybody has a plan until they get bitten by a black mamba.” That’s the scenario here, where an attempted kidnapping by German criminal Jacques Müller, a.k.a. Jacmel (Kinski) and his gang goes thoroughly pear-shaped, for two reasons. Firstly, associate Dave Averconnelly (Reed) blows away a policeman on the doorstep of the house, which causes the local police, under Commander William Bulloch (Williamson), to descend, en masse. Secondly, due to an

To mis-quote Mike Tyson, “Everybody has a plan until they get bitten by a black mamba.” That’s the scenario here, where an attempted kidnapping by German criminal Jacques Müller, a.k.a. Jacmel (Kinski) and his gang goes thoroughly pear-shaped, for two reasons. Firstly, associate Dave Averconnelly (Reed) blows away a policeman on the doorstep of the house, which causes the local police, under Commander William Bulloch (Williamson), to descend, en masse. Secondly, due to an

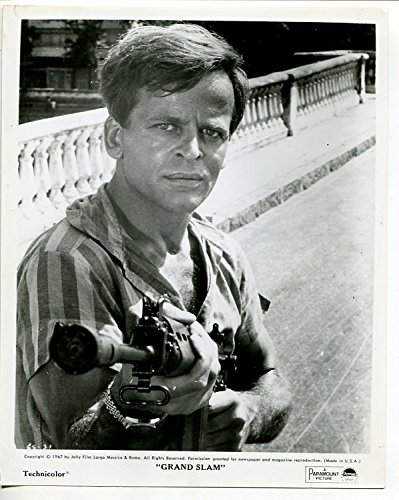

Trabucco (Matthau) is an assassin who has been hired to knock off three witnesses in an upcoming organized crime trial. The first two are blown up and poisoned with little trouble, but the third is held in protective custody until his appearance in court. Trabucco checks into a hotel opposite the courthouse, with a view of the steps, to await his target’s arrival. However, in the room next door is Victor Clooney (Lemmon), a neurotic TV executive who is estranged from his wife, Celia (Prentiss). When she rejects his attempts to reconcile, Victor attempts suicide; desperate to prevent the attention of hotel staff and, as a result, the authorities, Trabucco agrees to take responsibility for Clooney.

Trabucco (Matthau) is an assassin who has been hired to knock off three witnesses in an upcoming organized crime trial. The first two are blown up and poisoned with little trouble, but the third is held in protective custody until his appearance in court. Trabucco checks into a hotel opposite the courthouse, with a view of the steps, to await his target’s arrival. However, in the room next door is Victor Clooney (Lemmon), a neurotic TV executive who is estranged from his wife, Celia (Prentiss). When she rejects his attempts to reconcile, Victor attempts suicide; desperate to prevent the attention of hotel staff and, as a result, the authorities, Trabucco agrees to take responsibility for Clooney.

This is one of the films where Kinski’s character is not the focus, yet is essential to the plot. It’s Hagan’s actions that set things in motion, although at the bottom level, there isn’t much moral difference between him and Hamilton: both want revenge for the death of family members, and to kill those responsible. Despite this mirroring of motivation and action, there’s no doubt who’s the good guy and who’s the villain, as far as the film is concerned. Fidani is firmly in the Kid’s corner, portraying his vengeance as “righteous”, unlike Hagan’s. It’s an interesting double-standard. Perhaps it’s that Hagan is seen to be acting out of rage, while Hamilton’s response feels measured, more like justice is being meted out. We also know he’s correct in his choice of target: we never see who was behind the death of Hagan’s brothers.

This is one of the films where Kinski’s character is not the focus, yet is essential to the plot. It’s Hagan’s actions that set things in motion, although at the bottom level, there isn’t much moral difference between him and Hamilton: both want revenge for the death of family members, and to kill those responsible. Despite this mirroring of motivation and action, there’s no doubt who’s the good guy and who’s the villain, as far as the film is concerned. Fidani is firmly in the Kid’s corner, portraying his vengeance as “righteous”, unlike Hagan’s. It’s an interesting double-standard. Perhaps it’s that Hagan is seen to be acting out of rage, while Hamilton’s response feels measured, more like justice is being meted out. We also know he’s correct in his choice of target: we never see who was behind the death of Hagan’s brothers.