Dir: Shūji Terayama

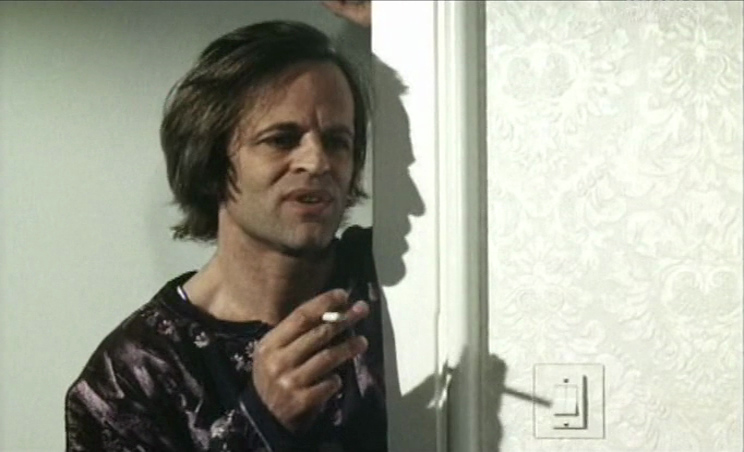

Star: Isabelle Illiers, Klaus Kinski, Arielle Dombasle, Kenichi Nakamura

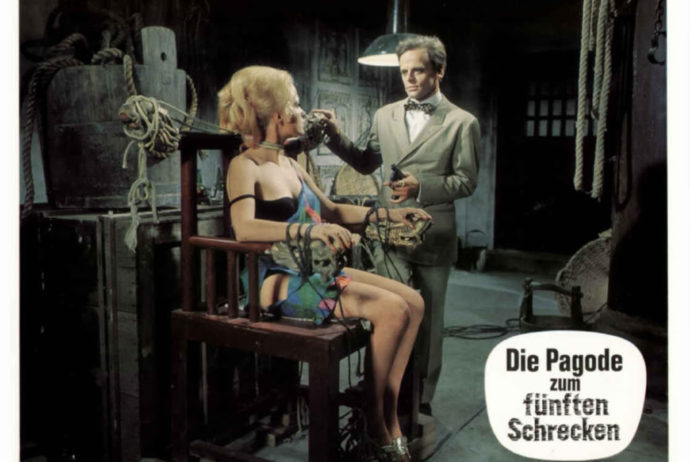

This ill-conceived sequel follows in the wake of 1975’s film version of The Story of O. Originally published in 1954, the novel was effectively a precursor to 50 Shades of Grey, depicting a consensually sado-masochistic relationship between the titular lady and Sir Stephen, the man who became her master. This movie is based on the sequel, Retour à Roissy (Return to Roissy), which came out in 1967. Despite that title, it’s set in Shanghai, with Sir Stephen (Kinski) taking O (Illiers) to become an employee in a Chinese brothel.

There, she has sex with various men, and becomes the subject of obsession of a young Chinese man (Nakamura), who glimpses her through the window of the brothel, and strives to accumulate enough money for a session with O. Meanwhile. Sir Stephen is having sex with his other mistress, Nathalie (Dombasle), after chaining O up and making her watch. There’s also a subplot about revolution being plotted by the downtrodden workers of Shanghai, with Sir Stephen being shaken down for contributions, and beaten up when he refuses to comply. Nathalie leaves Stephen, and when her younger suitor eventually saves up enough to get his wish, the lord sees O smile during the subsequent coupling; that cannot be tolerated, and he shoots dead his rival for her affections.

The seventies was a boom time for art-porn, and though this is a little late to the party, fits snugly and moistly into the same niche carved out by the likes of Walerian Borowczyk. Director Terayama was a multi-faceted artist, whose output included poetry, plays. photography and both short and feature films, before his death three years after this, from that preferred malady of tortured creative types, cirrhosis of the liver. I can’t say I’ve seen any of his other work, so can’t say how this compares, but it does have some beautifully composed scenes, demonstrating Terayama’s photographic eye.

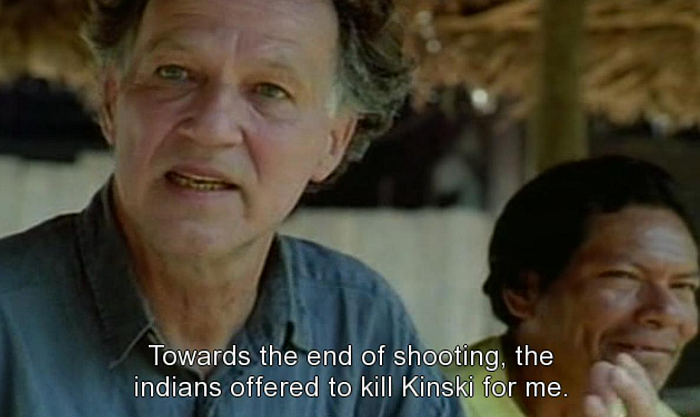

It also has more than I’d like of Klaus Kinski’s hairy arse, and I suspect the pitch which brought Klaus was on board was something like this:

“So you’ll get to visit Hong Kong and have sex with attractive women.”

“You mean, pretend to have sex with attractive women?”

“No, actually have sex with them.”

“What time does the flight leave?”

For if what we’re seeing here is not actual coitus, it’s a far more convincing imitation of it that is ever managed on Cinemax. Certainly the oral sex administered by O has real penis in her mouth, which lends credence to the theory Klaus wasn’t faking it either. This is particularly true of the first encounter, which sees Sir Stephen fucking – there’s no more descriptive word available for the steam-hammer pounding being delivered – one of the brothel’s whores. [Random note: while supposedly set in pre-war China, all the Chinese characters are played by Japanese actors and actresses]. All of the genuine carnality comes more that two decades before The Brown Bunny catapulted Chloë Sevigny to fame.

The problem is that, much like its more recent cousin, this film (“50 Shades of Klaus”, perhaps?) doesn’t have much to offer in terms of content, beyond its shock value. The original film, The Story of O, actually did a decent job of putting over the appeal of being on the M-end of a sado-masochistic relationship. While it still might not be something you would necessarily want to do yourself, you could at least see what participants might get out of it. Here? Absolutely nothing. There’s no sense of Sir Stephen and O having the slightest degree of mutual passion for each other. In fact, he doesn’t seem to care about her at all: the kind of stunts he demands of her in this, are more like things you’d do to get rid of a desperately-clingy girlfriend, rather than mutually beneficial attempts to cement your relationship.

This is particularly disappointing, since The Story of O‘s writer, Dominique Aury, co-wrote the script. But even outside of the sexual content, the rest of it is largely unconvincing, particularly the attempts at political commentary. At best, they dilute the focus, which should be on the Steven/O relationship with a fiery intensity. At worst – and this is much closer to where they lie – they have as much intellectual credibility as the opinions of an earnest high-school debate society geek. Even Kinski can’t do much to save proceedings, particularly in the dubbed version. It doesn’t help that his face is clad for much of the film in such an excess of white pancake make-up, I wondered if he was going to start walking into the wind or pretending to be inside an invisible box.

As noted earlier, Terayama knows his way around the camera, and the film does have some occasionally striking imagery and moments. O as a young girl, constrained by her father within a prison made entirely of chalk line on the ground (perhaps inspiring Lars Von Trier’s Dogville? That’s perhaps a stretch, but LVT has also showed himself not averse to including graphic sex in his movies either) One of the prostitutes is the only person who can hear music being played nearby, and after her suicide, the corpse rises out of the river by the brothel, on top of a grand piano. It’s the kind of grandiose moment which, logically, makes absolutely no sense, yet has to be applauded because of its insanity. There’s some creative use of filters, and overall, you can’t condemn the movie from a technical point of view.

From just about every other angle, however… Plenty of room for criticism, not least in that the sex scenes are virtually the only ones in which Klaus shows any enthusiasm for his role. It appears that Kinski wasn’t the only one in it purely for the paycheck either: Terayama supposedly took on the job, to finance some of his other artistic activities. It’s no surprise, therefore, that it comes off as far less memorable than, say, those works of Borowczyk such as La Bête. Successfully combining porn and art takes a significant degree of commitment, and it seems severely lacking from most of those involved here.

But just as they’re about to depart, the Russian stage an attack, and all men in uniform are recalled into action. The film ends with the mothers watching as their sons, once again, head off to face the enemy. “God in heaven, they’re really going back,” says the female pastor who has been part of the group. “Leave God out of it,” replies another mother. “It’s man’s doing. It’s always man’s doing…” The End. There is an alternative finale, which had me expecting a less downbeat version in which the families are re-united and escape from the front. Nope. It’s basically the same, only with slightly different final dialogue: instead of offering commentary about God and man, it’s a simple, “They’ve forgotten us. They will always forget us.” The End.

But just as they’re about to depart, the Russian stage an attack, and all men in uniform are recalled into action. The film ends with the mothers watching as their sons, once again, head off to face the enemy. “God in heaven, they’re really going back,” says the female pastor who has been part of the group. “Leave God out of it,” replies another mother. “It’s man’s doing. It’s always man’s doing…” The End. There is an alternative finale, which had me expecting a less downbeat version in which the families are re-united and escape from the front. Nope. It’s basically the same, only with slightly different final dialogue: instead of offering commentary about God and man, it’s a simple, “They’ve forgotten us. They will always forget us.” The End.

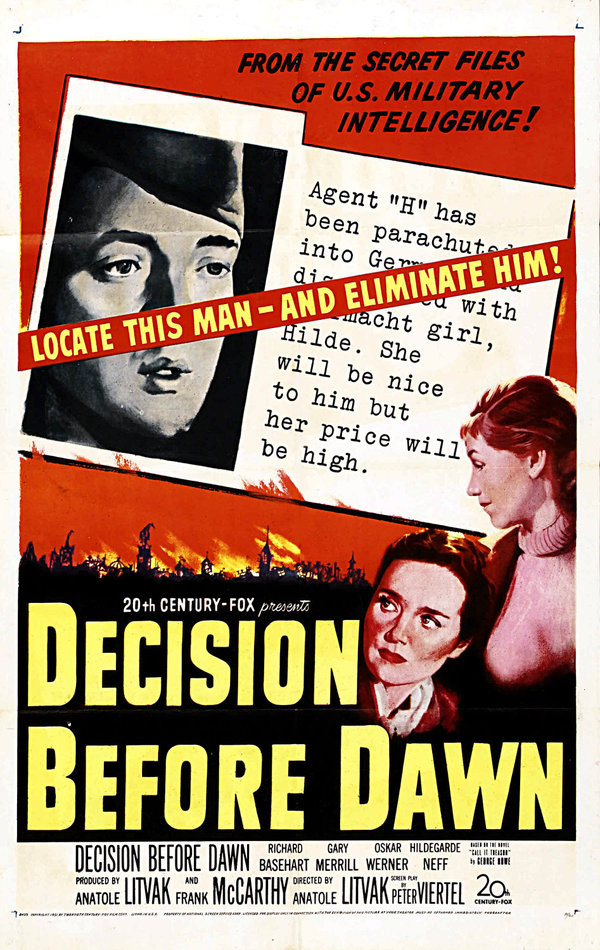

It takes place in the later stage of World War II, with the Allied forces closing in on Germany, but still facing a battle from the Nazi armies. Intelligence officer Colonel Devlin obtains permission from his superiors to recruit agents out of German prisoners of war, and send them them back into their country to obtain crucial intelligence about the location of Axis units. The two chosen are codenamed “Happy” (Werner) and “Tiger” (Blech), and are parachuted behind enemy lines, along with American communications specialist, Lieutenant Rennick (Basehart).

It takes place in the later stage of World War II, with the Allied forces closing in on Germany, but still facing a battle from the Nazi armies. Intelligence officer Colonel Devlin obtains permission from his superiors to recruit agents out of German prisoners of war, and send them them back into their country to obtain crucial intelligence about the location of Axis units. The two chosen are codenamed “Happy” (Werner) and “Tiger” (Blech), and are parachuted behind enemy lines, along with American communications specialist, Lieutenant Rennick (Basehart).

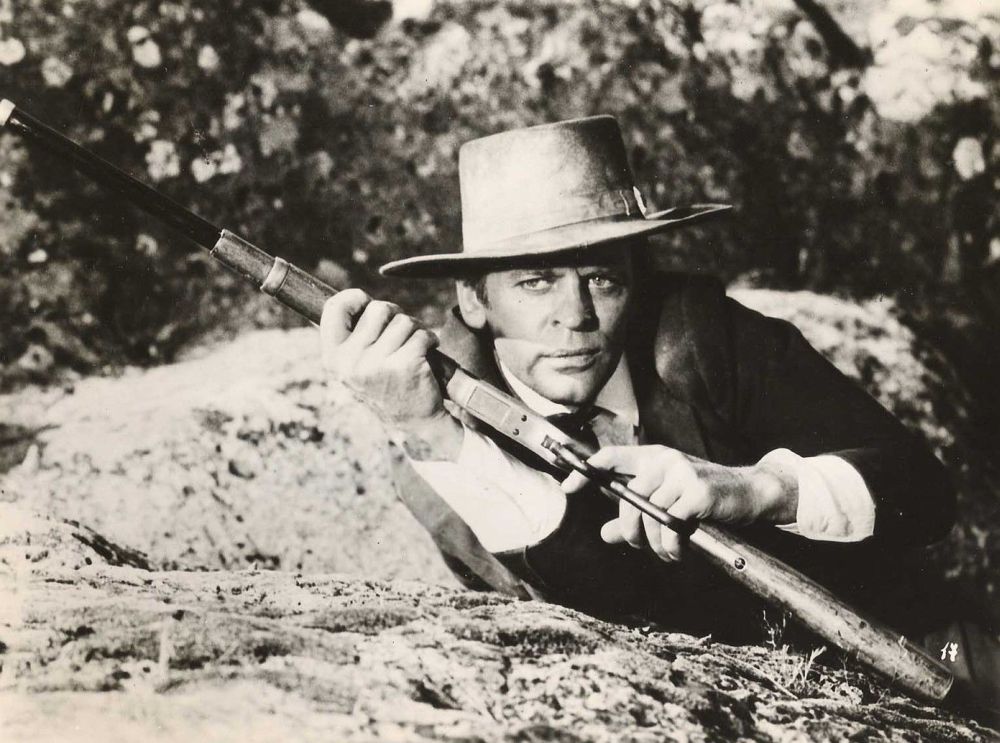

It opens with Don Jose (Nero), an officer in the Spanish army who is currently stationed in Seville. At a local factory, he encounters Carmen (Aumont), a ravishing Gypsy girl, who has just been given a job there. This doesn’t last long, after she takes offense at the comments of another worker, and Don Jose is given the job of escorting Carmen to the local police station. She deceives him and escapes, which leads to him being demoted down the ranks, but when they meet again, a passionate if destructive relationship begins.

It opens with Don Jose (Nero), an officer in the Spanish army who is currently stationed in Seville. At a local factory, he encounters Carmen (Aumont), a ravishing Gypsy girl, who has just been given a job there. This doesn’t last long, after she takes offense at the comments of another worker, and Don Jose is given the job of escorting Carmen to the local police station. She deceives him and escapes, which leads to him being demoted down the ranks, but when they meet again, a passionate if destructive relationship begins. Particularly in the first half, the pacing is significantly more stately than you might expect, with much more drama than action. But it never looks less than impressive, though that might just be the result of me knowing that future triple-Oscar winner Vittoria Storaro worked on this as a camera operator. Nero holds the attention of the audience as easily as you’d expect, and Aumont, the daughter of Maria Montez, is also effective enough in a role which feels as if it was written with Sophia Loren in mind. [Or even Gina Lollobrigida; her cousin, Guido, is actually in the cast]

Particularly in the first half, the pacing is significantly more stately than you might expect, with much more drama than action. But it never looks less than impressive, though that might just be the result of me knowing that future triple-Oscar winner Vittoria Storaro worked on this as a camera operator. Nero holds the attention of the audience as easily as you’d expect, and Aumont, the daughter of Maria Montez, is also effective enough in a role which feels as if it was written with Sophia Loren in mind. [Or even Gina Lollobrigida; her cousin, Guido, is actually in the cast]

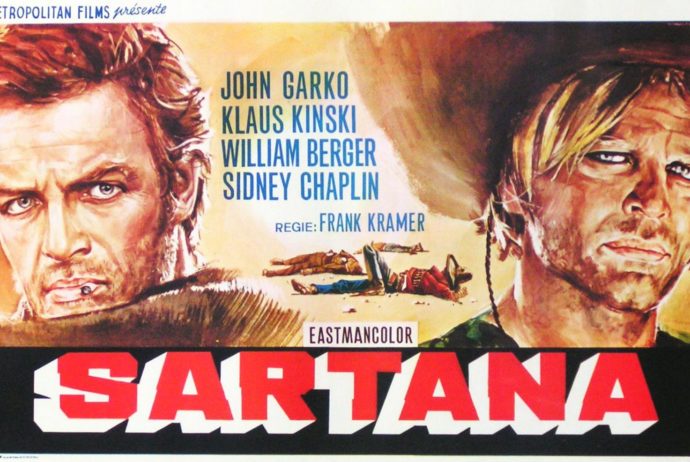

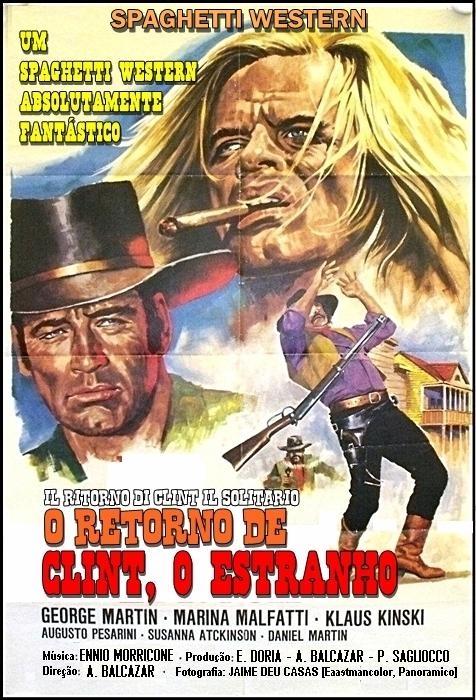

It’s apparently a semi-sequel, semi-remake of a film made five years earlier, Clint the Stranger. It also starred Martin, but for the sequel, both the hero and film were renamed in some territories, in order to cash in on the popularity of the previous year’s They Call Me Trinity, which is not related in any way. This was sometimes credited as being directed by Martin too, but appears instead to have been the work of Balcázar, who seems generally regarded as in the lower-tier of spaghetti Western auteurs. It wasn’t the first film in which Martin had appeared alongside Kinski; they had both also starred in

It’s apparently a semi-sequel, semi-remake of a film made five years earlier, Clint the Stranger. It also starred Martin, but for the sequel, both the hero and film were renamed in some territories, in order to cash in on the popularity of the previous year’s They Call Me Trinity, which is not related in any way. This was sometimes credited as being directed by Martin too, but appears instead to have been the work of Balcázar, who seems generally regarded as in the lower-tier of spaghetti Western auteurs. It wasn’t the first film in which Martin had appeared alongside Kinski; they had both also starred in

The lack of anything even remotely explicit probably works in the film’s best interests, since you will remember it, when a million soft-core flicks of the decade have long been forgotten. It’s apparently based on a book by the real Lynn Keefe, under the “How did a…” title. Though I imagine it’s probably as truly “autobiographical” as the book on which Nastassja’s Passion Flower Hotel was supposedly based. But, from the loss of the heroine’s pregnancy on, it seems to zig when you think it’s going to zag, and is all the better for it. I’ll even forgive the obvious stunt casting, since Sam’s fashion sense is a perfect time capsule of the era. There’s a certain tasty irony present, both in the character he plays and in him being on the receiving end of Lynn’s freak-out when she discovers he has blown all their cash.

The lack of anything even remotely explicit probably works in the film’s best interests, since you will remember it, when a million soft-core flicks of the decade have long been forgotten. It’s apparently based on a book by the real Lynn Keefe, under the “How did a…” title. Though I imagine it’s probably as truly “autobiographical” as the book on which Nastassja’s Passion Flower Hotel was supposedly based. But, from the loss of the heroine’s pregnancy on, it seems to zig when you think it’s going to zag, and is all the better for it. I’ll even forgive the obvious stunt casting, since Sam’s fashion sense is a perfect time capsule of the era. There’s a certain tasty irony present, both in the character he plays and in him being on the receiving end of Lynn’s freak-out when she discovers he has blown all their cash.

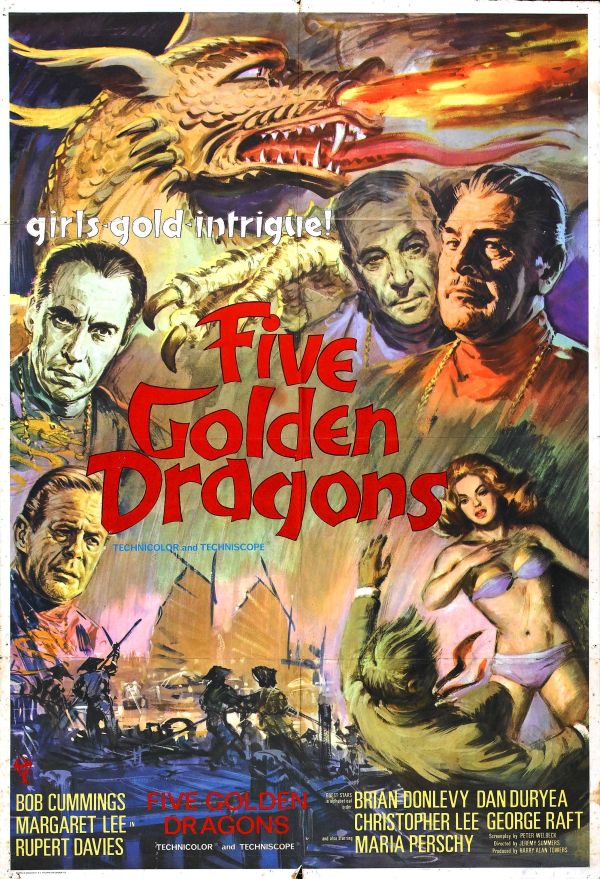

The parade of guest stars seems to solve a similar purpose. The Dragons are a strangely Caucasian lot, considering where they’re operating, being played by Dan Duryea, Brian Donlevy, George Raft and Christopher Lee, which is an impressive supporting cast. Or would be, if they were given anything meaningful to do. Instead, they get little more than two scenes, shot suspiciously indoors (particularly compared to the rest of the film, which flaunts its Hong Kongness with blatant abandon), so you wonder if they even got a weekend in the colony out of it. I think the appearance of Japanese guest singer Yukari Ito also falls into this category, apparently a shallow and rather obvious early stab at the international box-office.

The parade of guest stars seems to solve a similar purpose. The Dragons are a strangely Caucasian lot, considering where they’re operating, being played by Dan Duryea, Brian Donlevy, George Raft and Christopher Lee, which is an impressive supporting cast. Or would be, if they were given anything meaningful to do. Instead, they get little more than two scenes, shot suspiciously indoors (particularly compared to the rest of the film, which flaunts its Hong Kongness with blatant abandon), so you wonder if they even got a weekend in the colony out of it. I think the appearance of Japanese guest singer Yukari Ito also falls into this category, apparently a shallow and rather obvious early stab at the international box-office.