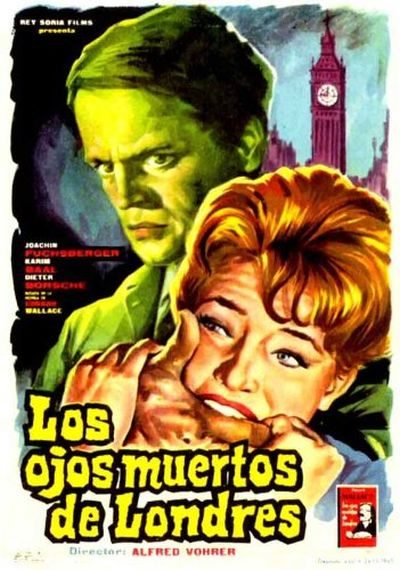

Dir: Alfred Vohrer

Star: Joachim Fuchsberger, Karin Baal, Dieter Borsche, Klaus Kinski

The Edgar Wallace novel had previously been adapted into a British film, The Dark Eyes of London, starring Bela Lugosi in the role of the insurance agent. Released just at the opening of World War 2, in November 1939, it was the first British film to be given the “H” certificate by UK censors, for horrific content. Proving quite successful in Germany, it was an obvious choice for a local version, two decades later. It was the first adaptation directed by Vohrer, who’d go on to become one of the mainstay helmers in the field, with a total of fourteen Wallace-inspired stories to his credit before the end of the sixties. This one is perhaps darker in tone than most, and seems almost to be inspired as much by Italian giallo films as the krimis with which I’m becoming increasingly familiar over the course of this project.

The hero is Scotland Yard’s Inspector Larry Holt (Fuchsberger), who is investigating a series of deaths by drowning in the Thames, which he’s convinced are murders, even though the forensic evidence suggest accidental demises. We know from the start that he’s onto something, having watched as Blind Jack, a hulking bald brute with cloudy eyes, attacks his chosen victim, an Australian wool merchant. A Braille note found in the victim’s pocket brings in specialist Nora Ward (Baal), who helps uncover a possible link to “The Dead Eyes of London,” an organized criminal group of blind beggars, and a mission for sightless old men run by the Reverend Paul Dearborn.

The hero is Scotland Yard’s Inspector Larry Holt (Fuchsberger), who is investigating a series of deaths by drowning in the Thames, which he’s convinced are murders, even though the forensic evidence suggest accidental demises. We know from the start that he’s onto something, having watched as Blind Jack, a hulking bald brute with cloudy eyes, attacks his chosen victim, an Australian wool merchant. A Braille note found in the victim’s pocket brings in specialist Nora Ward (Baal), who helps uncover a possible link to “The Dead Eyes of London,” an organized criminal group of blind beggars, and a mission for sightless old men run by the Reverend Paul Dearborn.

Discovering a life policy held by the corpse leads Holt to the Greenwich insurance company, run by David Judd (Borsche), since the death of his brother, Stephan. It turns out they have ties to the other corpses fished out of the river, and have had to pay out on the claims, because the deaths were officially certified as accidents. Meanwhile, Judd’s secretary, Edgar Strauss (Kinski) has a criminal record for fraud, a gambling habit and a fondness for wearing mirror shades in every situation. Might he, possibly, have something to do with the murders?

Oh, who am I trying to kid? It’s Klaus Kinski in mirror shades. Of course he does, as if his glowering (albeit sickly-looking) presence on the Spanish poster wasn’t a dead giveaway. Though it has to be said in the film’s defense, Strauss is just one element in a very twisted tale, and I’ll go as far as to say, not even the central one. This area is perhaps where the movie has most in common with the giallo: an incredibly complicated plot, on which it’s probably best not to breathe too hard, for fear of the entire thing collapsing into a heap of “I’m so sure…” implausibilities. In this case, it seems as if the majority of the characters are not who they claim to be; some of these assumed personas are more credible than others.

The fraud plan particularly doesn’t seem to stand up to any degree of scrutiny, not least in the way all the victims are insured by the same company. If I was pulling off this kind of scheme, that approach would seem immediately to invite unwanted attention from the authorities – and this is exactly what happens here. If I were an evil criminal mastermind, I might also be inclined to have a range of different “accidents” befall the victims too, rather than drowning them in the same location. Again, the similarity in the deaths, allows the police to draw a connecting line between them far too easily.

Much like the best giallos, however, it knocks the atmosphere thing out of the park. The London depicted is apparently perpetually blanketed in fog, in a manner which suggest the Clean Air Act passed five years earlier had never gone into effect, with the last real “pea-souper” actually being in 1952. I lived in the city for more than a decade and never saw anything like the phenomenon depicted here. However, I won’t deny the impact of the meteorological license, with the eerie, almost deserted streets, and shadows in which anything could conceivably lurk – up to and including a sightless vagrant with murderous intent. [Blind Jack is played by Adi Berber, who brings a physical presence to his portrayal which reminded me of Tor Johnson, the ex-pro wrestler frequently used by Ed Wood, Jr.]

There are some surreal stylistic flourishes, such as the shot of a man cleaning his teeth which is filmed from inside his mouth. While it’s certainly something I don’t recall having seen before, the obvious question is: why? It’s a surreal moment largely out of stylistic keeping with the rest of the film, though the movie has some other odd physical elements, such as a skull which doubles as a pop-up cigarette dispenser, and a booby-trapped television set that shoots at the viewer. On the other hand, there are the comedic stylings of Eddie Arent as Inspector Holt’s sidekick, Sergeant Sunny Harvey, who knits jerseys to relieve stress.

After taking a bit to get going, this does eventually reach a decent speed, even if some aspects do require a healthy quote of disbelief suspension. By the end, it’s almost a giallo-Gothic cross-breed, with the heroine victim facing some particularly nasty potential deaths. Particular praise goes to the appropriately named Heinz Funk’s score, which occasionally borders on the electronically experimental, before dropping back a few centuries for a bit of the old Ludwig Van, to accompany bits of the (somewhat ultra-, given the date) violence. Kinski’s role is more of a supporting one, significantly oversold by the poster above, yet he slips into his character like a well-worn, slightly threadbare suit, inhabiting it as if he has been there all his life. This turned out to be something of a breakthrough performance for Klaus: reportedly, the film “was a huge hit when it was released and earned Kinski a title story in the very influential news magazine Der Spiegel, exposing him for the first time to a broader audience.”