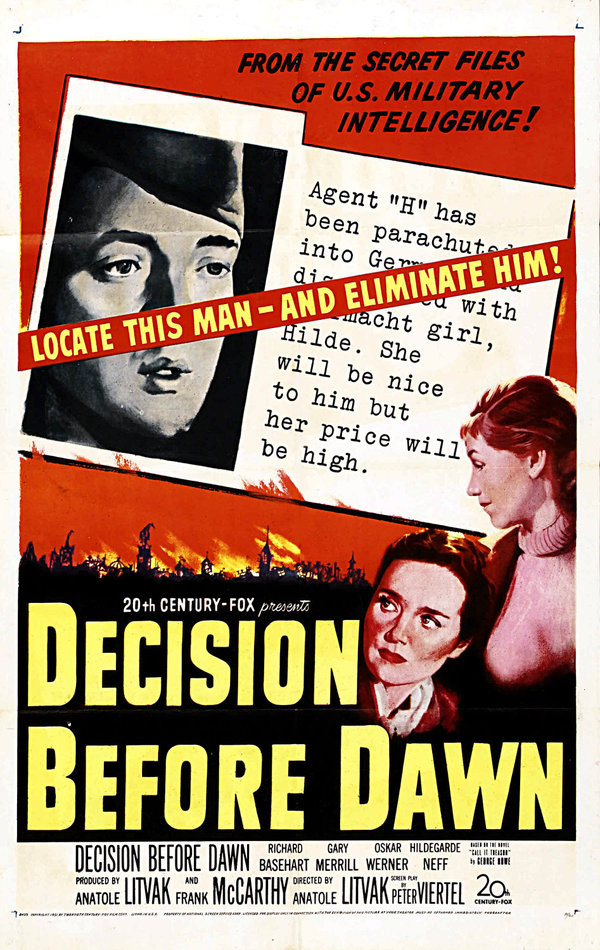

Dir: Anatole Litvak

Star: Richard Basehart, Oskar Werner, Hans Christian Blech, Klaus Kinski (uncredited)

On the one hand, got to be impressed that the second movie in which Klaus appeared, was nominated as Best Picture at the Academy Awards. On the other, it must be admitted that his single-scene, uncredited contribution was likely not responsible for the recognition. I also have to wonder if 1951 was a poor year for cinema. Not that this is a “bad” movie. It just doesn’t seem very Oscar-worthy – and, indeed lost out on the award, to An American in Paris. [Although, to answer my own question: the same gala also honored A Streetcar Named Desire and The African Queen, so the year didn’t suck]

It takes place in the later stage of World War II, with the Allied forces closing in on Germany, but still facing a battle from the Nazi armies. Intelligence officer Colonel Devlin obtains permission from his superiors to recruit agents out of German prisoners of war, and send them them back into their country to obtain crucial intelligence about the location of Axis units. The two chosen are codenamed “Happy” (Werner) and “Tiger” (Blech), and are parachuted behind enemy lines, along with American communications specialist, Lieutenant Rennick (Basehart).

It takes place in the later stage of World War II, with the Allied forces closing in on Germany, but still facing a battle from the Nazi armies. Intelligence officer Colonel Devlin obtains permission from his superiors to recruit agents out of German prisoners of war, and send them them back into their country to obtain crucial intelligence about the location of Axis units. The two chosen are codenamed “Happy” (Werner) and “Tiger” (Blech), and are parachuted behind enemy lines, along with American communications specialist, Lieutenant Rennick (Basehart).

Happy becomes the main focus of the film at this point, which is perhaps part of the problem. For at the start, it looked like Rennick, newly assigned to the intelligence group, was going to be the hero. But after touching down, Rennick and Tiger peel off, and we are suddenly following Happy as he makes his way through the bombed-out landscape of 1944 Germany. On his journey, he meets people of all types and levels: civilians and soldiers, ardent Nazis and Allied sympathizers, colonels and whores. Having obtained the needed information, Happy heads for Mannheim to link up with Tiger and Rennick, and head back to friendly territory. Except, getting home may be the most dangerous part of the mission.

A major selling point here is it being shot on location in Germany – or, as the trailer puts it, “Filmed at the burning crossroads of the world… where it ACTUALLY HAPPENED!” [capital letters as in original] This was made five years after the war ended, but there seemed still to be no shortage of bomb-sites for the film-makers to use; the one which is supposedly a theater is particularly effective. It does seem a bit soon to have Hollywood parking up, on what remains of your streets. I vaguely remember a B-movie guy (Albert Pyun?), making movies in somewhere like Sarajevo right after the civil war there, and that seems the level of exploitation hustle I’d expect to pull off this kind of thing.

It feels like a “war procedural”, for want of a better term, with a script endlessly fascinated with minutiae like the contents of Happy’s mission kit, right down to the precise maps included in it. Sometimes this matters – a detail concerning Nazi documentation turns out to be quite important later on. However, a lot of it isn’t at all necessary, and comes over as padding, especially in a film that runs close to two hours, and this in an era before there were 10 minutes of credits at the end of any epic film. This isn’t to say there are no sequences of merit or excitement. Just that there aren’t enough of them, and it instead feels too much like an apologia for the inhabitants of Germany who, with one exception, seem more like victims. I was left wondering why were we invading.

To Kinski’s brief contribution. You’d better have your popcorn ready and close to hand, because his entire screen time in this one lasts 12 seconds, and is over before the 11th minute of the film has ended. It comes when the Americans are interviewing potential candidates for their undercover mission. “I have never been interested in politics,” says Klaus, sounding disturbingly like a young Peter Lorre. However, he is rudely dismissed, without being able to get any further than his elevator pitch, never to be seen again. If you want to save yourself approximately one hour and fifty-seven minutes, here you go. You’re welcome!

The film claims to be based on a true story, with the names changed. It’s hard to be certain, but it’s quite possible this is the case, at least loosely. The film is based on a 1949 novel, Call It Treason, by George Howe. He was in the military during World War 2, Howe serving with the Office of Strategic Services (the forerunner of the CIA), and the U.S. Seventh Army in both Algeria and France, so could well have come in contact with similar agents. [The book is dedicated, “To Happy, 1925-1945”] The author was responsible for documentation and cover stories, which may go some way to explain the movie version’s resulting (over-)devotion to detail, reflecting similar content in the book; I believe scriptwriter Peter Viertel served in the same unit.

It does possess a level of authenticity which you could only get at the time, and has now been lost forever. For example, Oskar Werner isn’t just playing a Nazi soldier. Like Kinski, he actually served in the Wehrmacht during World War 2, deserting in December 1944. It’s easy to forget, almost every German on-screen here had direct, personal experience of the events being depicted, which is chilling to think about. Still, while I am inclined to read the book, this is probably the kind of story that works better overall, on paper than screen.