Dir: Josef von Báky

Star: Brigitte Grothum, Joachim Fuchsberger, Edith Hancke, Klaus Kinski

a.k.a. The Strange Countess

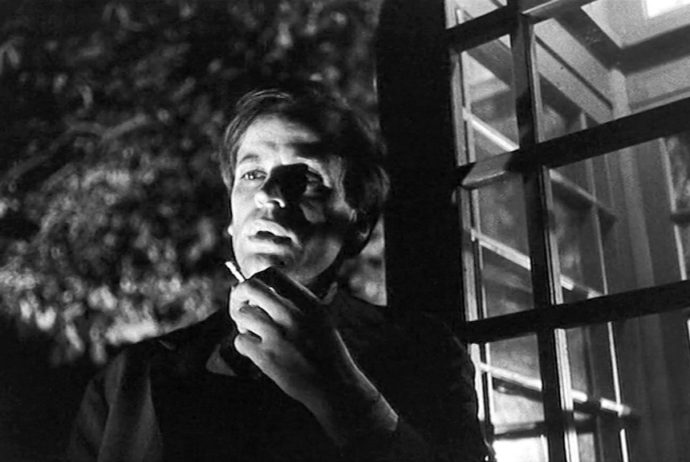

We don’t have to wait long for Klaus to show up in this one. Indeed, the very first shot of the movie, as the opening credits roll, see his character lurking suspiciously in a doorway. From there, he moseys his way slowly along the “London” streets, although like almost all Edgar Wallace krimis, any English elements were largely faked with stock footage, Here’s the Britishness is established with a phone box and a close-up of the London telephone directory. For Klaus is about to make a threatening telephone call to Margaret Reedle (Grothum). And even at this early stage in his career, nobody can issue a not-so veiled threat, quite like Mr. Kinski. “This will be your last quiet night,” he calmly tells her, before pausing to enjoy an almost orgasmic post-call cigarette (top).

He certainly tries to make good on his promise. Miss Reedle is about to leave her position at a solicitor’s to become the private secretary to nobility – albeit one with the very unfortunate name of Countess Moron, I kid you not. I can only guess something was lost in translation there. [The Countess is played by legendary German actress Lil Dagover, who was the female lead in The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, and was still acting into her nineties.] However, Margaret may not live to see her new job. In just one day, there are three attempts on her life. First, a building site accident, then a car bomb and finally, a box of chocolates with enough Prussic acid to kill ten people. Fortunately, she has a guardian angel in Mike Dorn (Fuchsberger), a detective from Scotland Yard, called in by her current employer, Mr. Shaddle, because he fears for her safety.

Margaret proceeds with her new employment, only for the assassination attempts to continue, such as a balcony collapsing under her. The threatening phone calls from Stuart Bresset (Kinski) are ongoing as well, from the asylum where he is confined. According to Bresset’s mad ravings, he was promised his freedom by Dr. Tappat, director of the institution where he is incarcerated, in exchange for killing Margaret. This does at least explain the rather lax security, allowing Bresset to come and go as he pleases. However, I’m still not sure why he is allowed to make those calls – at one point, even using a phone in the asylum. It’s a bit of a giveaway, and I’d have said warning your potential victim also decreases substantially the chance of success. I guess this is what happens when you contract with a madman to do your dirty work.

The key question is, of course, why is Margaret a target? It seems to be related to the case of Mary Pinder, a woman who was convicted of poisoning her husband. Initially sentenced to death, the term was commuted to 20 years in prison after it was found that Mary is pregnant. She has just been released from prison, and been hired by Countess Moron (sorry, it just does not get any better with repetition) as a housekeeper. Looking through the case’s paperwork, courtesy of Mr. Shaddle, Margaret discovers her late mother was the only defense witness at Mary’s trial. Turns out, there’s even more of a connection, though I’d better leave that for the film to reveal. Dorn, doing his own investigation, finds out that the Countess’s son, Selwyn (Eddi Arendt, in a more restrained role than his usual comic relief), is the heir to the family fortune. However, this is only due to the disappearance of her elder brother, some twenty years previously.

Needless to say, this is all tied together, with one of those typically messy and convoluted plans, which I suspect no criminal in the real world would ever attempt. Yet, if you can suspend your disbelief, this should still make for a decent bit of entertainment. The performances are winning across the board; I have a particular fondness for Edith Hancke as Margaret’s plucky and loyal friend, Lizzy Smith. She sticks by her pal, when many less-resolute associates would be wishing them all the very best in their future endeavours. Dagover, too, gets a chance to demonstrate why she was such an icon. In particular at the end, when all the schemes come crashing down around her ears, and leave the Countess Moron (nope…) with only one credible way out.

Though credited to von Báky, he fell ill during shooting, and had to hand over the reins to Jürgen Roland. You can’t tell, and both men deserve credit for managing to handle what could well have become a confusing plot with some skill, stopping it from becoming incomprehensible. We are, however, here to see Klaus Kinski playing a madman, and he delivers in a way that renders almost all flaws, big and small, close to irrelevant. Right from the start, it’s clear there’s something not right about Bresset, even if it’s not initially apparent whether he is responsible for the attempts on Margaret’s life, or trying to save her from them. [The answer turns out to be, I would say, a little from Column A, and a little from Column B]

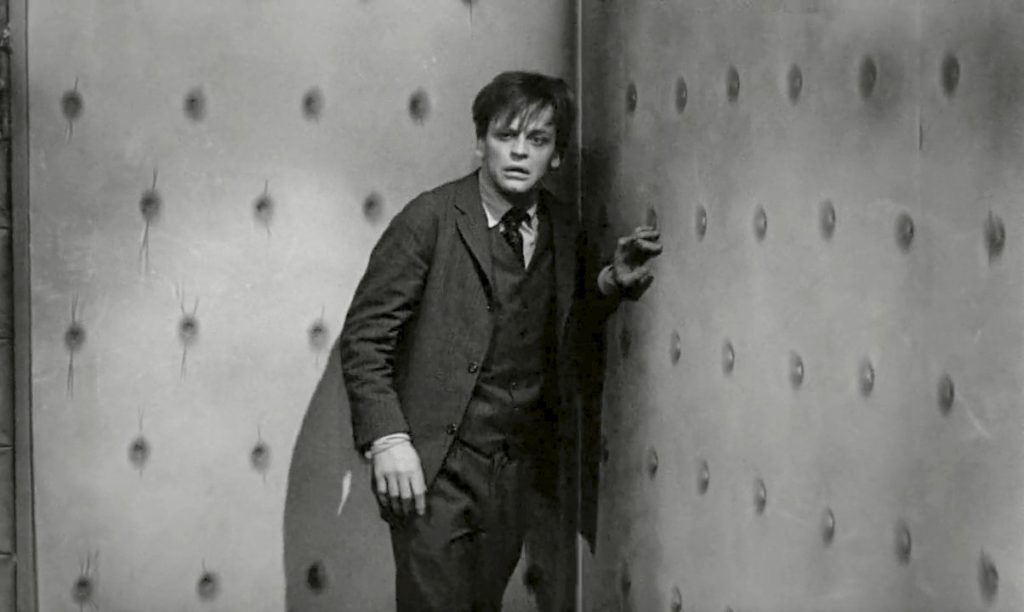

Likely in line with the somewhat murky nature of the film as a whole, his fate remains uncertain. He does certainly make it to the final 10 minutes. There, he engages in a brawl with Dorn in Tappat’s surgery, after the policeman has broken into the asylum, in search of Margaret, and finds Bresset about to complete his mission with a scalpel (above). It’s strikingly filmed, shot from both ends of the hospital table around which they are struggling. The fight finishes with Dorn despatching his opponent, using a couple of (let’s be honest, fairly woeful) karate chops. He exits with Margaret, leaving Bresset unconscious on the floor, and that’s the last we see of Klaus. I feel somewhat sorry for him: the character may be a psychopathic, failed wannabe killer, yet there’s no denying Bresset did his best, and certainly put in a lot of effort. Got to respect a lunatic with a work ethic.