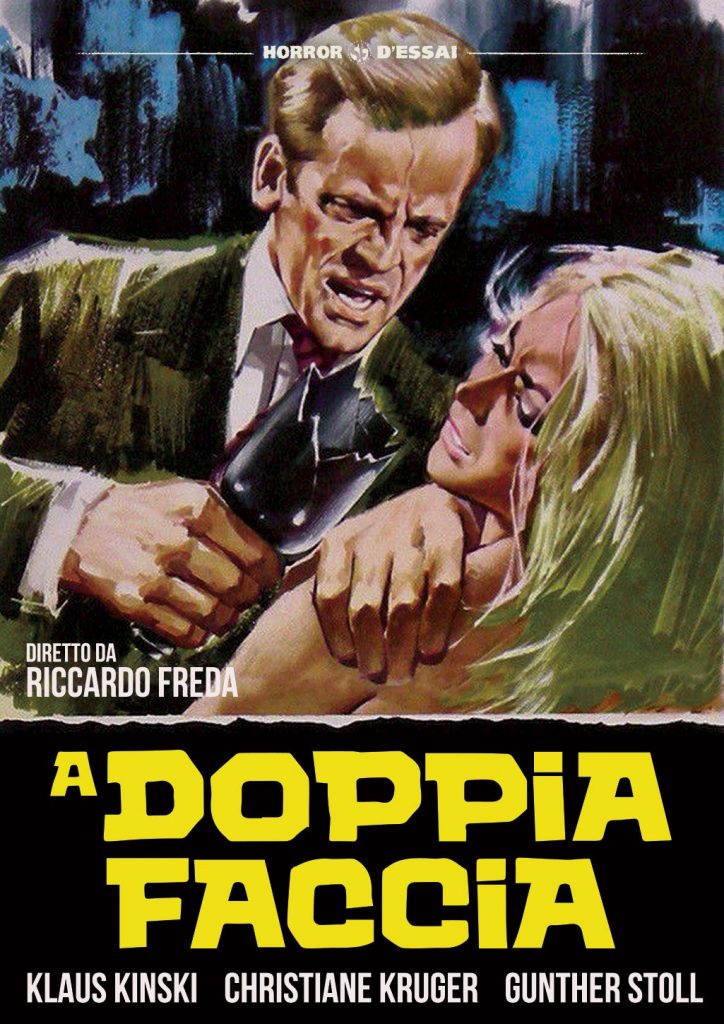

Dir: Riccardo Freda

Star: Klaus Kinski, Christiane Krüger, Sydney Chaplin, Günther Stoll

Like And God Said to Cain, this is a relatively rare film in which Kinski’s character is as much victim as victimizer – though also as there, it would likely be a bit of a stretch to call him “heroic.” He plays John Alexander, who married into wealth after wedding Helen (Margaret Lee), the owner of a successful company, who inherited it from her mother. After an initial honeymoon period, their relationship is now sinking fast, with neither partner remaining faithful. John is, at least, trying to be relatively discreet in an affair with his secretary. Helen, on the other hand, basically flaunts her lover, an actress named Liz, in her husband’s face.

Helen is then, apparently, killed in a car accident. I saw “apparently” for two reasons. Firstly, the audience sees the hands of a figure planting an explosive device on her sports car, so we know it’s no accident – it takes the police considerably longer to reach that conclusion. And, secondly, the body of Helen was “burned beyond recognition”. If I’ve learned anything from this kind of film, it’s that this inevitably means the corpse isn’t who you think it is. While this film does pre-date the use of DNA profiling, you’d think authorities might have looked into dental records. In their defense, there’s no reason for them to think it’s anyone other than Helen.

After a few weeks of mourning, John returns home to find the shower occupied by a bit of teenage Eurototty, Christine (Krüger). She turns out to be an actress in stag movies, and when she shows John her latest work, shot just a couple of days ago, he’s staggered to see elements strongly suggesting her veiled co-star is his supposedly dead wife. [As an aside, this felt a bit like a plot thread in Get Carter, made two years later] He starts trying to find out the identity of the participant, buying the film from its producer. However, the cops, under Inspector Stevens (Stoll), discover the truth about Helen’s death, and as the main beneficiary, John becomes suspect #1. When he shows the film to his father-in-law (Chaplin, the son of Charlie), evidence of it being Helen, such as a prominent neck scar, is no longer present.

So did John imagine it all? Or is he the target of a complex conspiracy? In this kind of film, which straddles the genres of Italian giallo and German krimi, it could be either. There was a point at which I was increasingly convinced that Christine was merely a figment of his deranged imagination, as it seemed that he was the only person who could see her. This was particularly the case during an extended sequence (okay, it’s only about 3½ minutes – it just feels a lot longer) where he follows her into the sixties version of a rave. This proves that young people have been getting off their faces in shit clubs while listening to worse music, and to the disapproval of adults, for over fifty years now.

After early effort to paint John as potentially Helen’s killer, it becomes clear that he genuinely did love her. The movie implies his affair was a reaction to her spurning, not only his affection, but that of the entire male gender. This would have to be a blow to any man’s self-confidence. Despite the early gloved killer, it does likely skew closer to the krimi field, even if the body-count is… well, one, which is considerably lower than usual, or indeed most giallo films. Plenty of nudity though, and other elements feel almost gothic, e.g. John wandering around by candlelight (below). While not based on a work by Edgar Wallace, it was advertised as such in Germany. It flopped so badly there, it caused a two-year hiatus in Rialto Films’ long-running series of Wallace adaptations, many of which had starred Kinski.

There is a definite sense of John gradually falling apart under the pressure of not knowing if his wife is dead or alive. At a couple of points, he cracks and teeters on the edge of unpleasant savagery. The ending, where he drinks heavily then gets a message to meet his “dead” wife at the deserted cathedral of St. Anne’s is likely the most obvious. Only the timely arrival of Inspector Stevens likely prevents John from becoming the murderer he is suspected of being. Yet there, he’s being manipulated into violence. Perhaps more telling is an earlier scene, where John breaks a bottle and threatens to slice up Christine’s face with it unless she talks, as shown in the poster (above). This is considerably closer to the Kinski we’ve come to expect.

Technically, the production is a bit variable, to put it mildly. The crash between a train and a car with which the film opens, is barely of the Hot Wheels level. There’s also some early green-screen work which is so bad, they probably shouldn’t have bothered. However, while the film clearly was not made in London as a whole, it’s a nice bit of period atmosphere to see Klaus strolling the neon-lit streets around Piccadilly Circus in swinging Lonson. At one point, he crosses the road in front of a cinema showing Where Eagles Dare. This would likely pin-point shooting as late 1968 or early 1969, since that film was released in the UK on December 4, 1968.

In truth, it does occupy a somewhat uncomfortable ground between genres, and it might have been better had Freda gone full-bore in one direction or another. While it’s a good role for Kinski, and he does a fine job of capturing the ambivalence of the character, the supporting cast are largely forgettable. Reportedly, Kinski didn’t get on with Freda and walked off the production until the director threatened to use a stand-in. There’s no mention of this in Klaus’s autobiography. But in the original version, All You Need is Love, is a section apparently referring to shooting this film in London (it mentions “Christine, my partner in the movie”), which is not present in Kinski Uncut.

This is mostly fairly banal, the usual sex and drugs shenanigans. It seems to mention Donyalle Luna, the first black supermodel, which could perhaps be why it was cut. Though since she died of a heroin overdoes in 1979, it’s hard to imagine her getting upset over the report of her “shooting up hard stuff into her veins.” But I was amused by this: “In London, I’m so stoned on hash that I lay down naked in the icy wind on the concrete balcony of my suite in the Hilton. When I come to, I eat eleven club sandwiches and drink three quarts of cold milk.” That certainly has the ring of Kinski-esque truth to it.