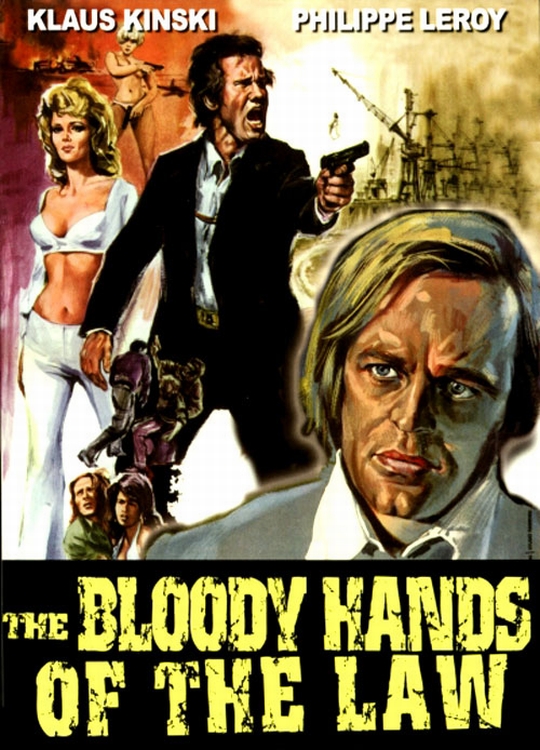

Dir: Mario Gariazzo

Star: Philippe Leroy, Tony Norton, Sylvia Monti, Klaus Kinski

a.k.a. The Bloody Hands of the Law

The force of organized crime is reaching out with impunity in contemporary Italy, under the control of the mysterious Vito Quattroni (Kinski). The film opens with the assassination of crime family member Frank Esposito, who is recuperating in hospital, under police custody. Obviously, this triggers a massive police investigation. Though the cop in charge, Commissario Gianni De Carmine (Leroy) feels handcuffed by the new approach to policing, and would far rather continue his approach, which largely consists of extracting confessions from people through violence.

It doesn’t help that any time progress is made, and a potential witness found by authorities, Quattroni and his minions quickly tidy up the loose end by killing them before they can provide any useful evidence. It’s apparent that there’s someone inside the police, feeding information to the bad guys which allows them to keep one step ahead of the police. De Carmine, in between bouts of lounging around in bed with wife Linda (Monti), decides that the only way he can match them, is to go all lone wolf, and revert to his former, punchier methods of investigation. It’s kinda a case of “If you can’t beat them… Well, go ahead and beat them anyway.”

The seventies was very much a time of change for police around the world, with the concept of rights for those in custody becoming more prevalent. The tension between this and “old-school” officers was a common source of inspiration for fictional police, and not just in Italy. Dirty Harry (1971) was probably the source for many. Though what comes most immediately to mind as a comparison for this is British TV show The Sweeney, which was a huge success from 1975-78. In it, John Thaw played a London equivalent of De Carmine – which meant running round and yelling “You’re nicked, my son!” at suspects, before or after pounding them into submission.

These all tended to have a sympathy for their protagonists, who were typically depicted as well intentioned law officers, who needed to be able to play the criminals without restriction, in order to defeat them. That’s certainly the case here: it’s only when De Carmine reverts to form that he is effectively able to combat Quattroni. This is partly due to the departmental mole becoming useless as a result, and unable to raise the alarm. Yet it also relies on the effectiveness of the hero’s robust methods, and tacitly endorses them as a result. Of course, the Mafia in seventies Italy was undeniably a serious problem, likely more so than organized crime in most other Western countries.

However, there’s a twist at the end, when De Carmine discovers the true “power behind the throne,” in terms of Quattroni carrying out their orders. For it turns out, rather than being traditional organized crime, to be an international group of stock traders, located on Wall Street. By manipulating events, and knowing about them in advance, they can take advantage of the changes in share price which result. This feels an interesting foreshadowing towards the dark nexus between crime, business and government, which would blossom in Italy into the notorious P2 scandal, early in the eighties.

Kinski’s portrayal of Vito Quattroni is certainly one of the less voluble of his career, to put it mildly. Indeed, I’m not sure he says anything of note. Or, possibly, anything at all, leaving the talking to his sidekick. But he still delivers the film’s most memorable scene and one that certainly ranks in any top 10 list of “Klaus’s characters do some really fucked-up shit”. One of Quattroni’s henchmen has succeeded in abducting a witness, and is holding her for his boss in an garage. While waiting there, he’s flicking through a porno mag, and gets the idea that molesting the witness is a good way of passing the time. However, Quattroni’s opinion on the matter when he shows up differs quite considerably…

It’s not like he’s gallantly riding to the rescue. For after he tenderly pulls the woman’s clothes back over her half-naked body, he immediately pulls a revolver, presses it to her side and shoots the witness dead. Quattroni then turns to his naughty associate, who is now being held firmly in the grasp of Quattroni’s sidekick. This being a garage, there are all manner of tools around. Quattroni reaches for the blow-torch, pulls out and puts on his aviators shades (below), gets the torch ablaze… and applies it to the wannabe rapist’s crotch. It’s nice to see even criminals can have a zero tolerance policy for sexual abuse, and you get the impression Quattroni and De Carmine may not be as far apart morally as you’d expect.

It’s a shame they don’t get to share the screen more, as it’d make for an interesting dynamic, like Pacino/De Niro in Heat. Instead, when De Carmine eventually get the tip he has been waiting for, that his quarry is in a roadhouse, this leads to a car-chase through the Italian countryside. Quattroni’s vehicle plunges over an embankment, but that doesn’t stop him from trying to unleash a hail of lead on his pursuers. Of course, De Carmine gets to yell the Italian equivalent of “You’re nicked, my son,” and his enthusiastic interrogation technique soon has Quattroni singing like a canary.

That, effectively, is the end of Kinski’s contribution to the movie, and it kinda peters out from there. It becomes clear that Quattroni is more of a bit player, just a cog in a far larger machine – which makes De Carmine’s obsession with catching him for the vast bulk of the running time, rather pointless. However, I guess that ties in well to the film’s generally cynical attitude towards justice in general, and the task of law enforcement in particular. I have a sneaking admiration for movies like that, and as a snapshot of seventies style, mentality and morality, it offers considerably more than a worthless time-capsule.