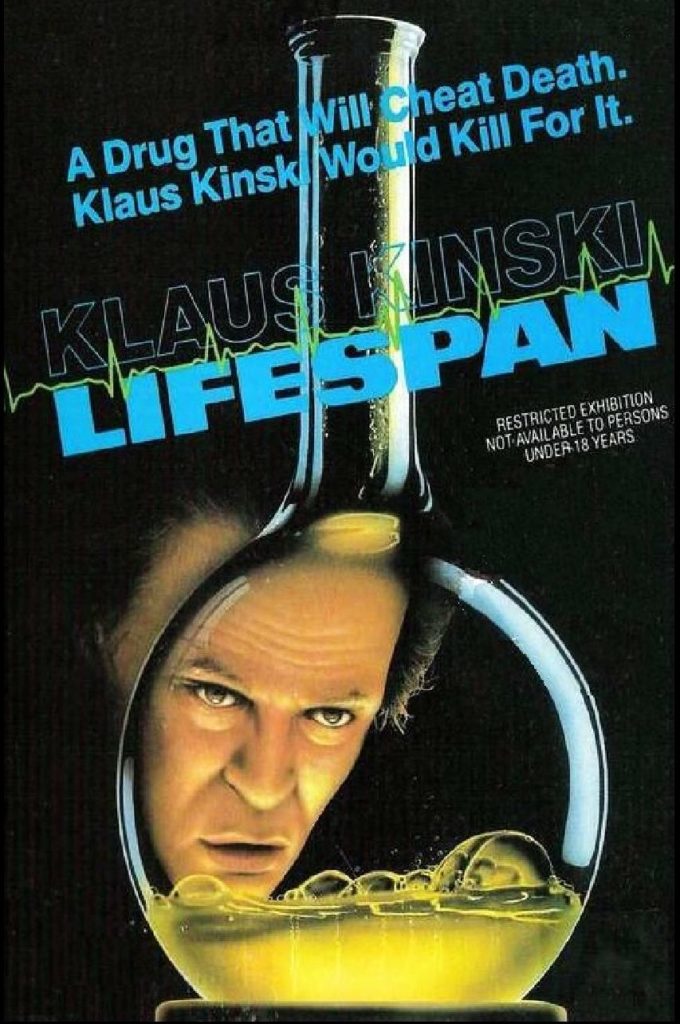

Dir: Sandy Whitelaw

Star: Hiram Keller, Tina Aumont, Klaus Kinski, Fons Rademakers

This is just an odd entity. On the surface, it’s not a very good movie about scientific morality, or in particular, the lack thereof. However, there’s an argument to be made that it perhaps has hidden depths, with layers of meaning lurking beneath the surface, if you care to unpack it. On the other hand… Nah, I’m good. In all honesty, I can’t be bothered to put the necessary effort in, which would be required for a detailed analysis. I’m perfectly fine with leaving it at being a not very good movie about immorality and immortality.

The central character is Dr. Ben Land (Keller), the son of a plastic surgeon. He has also gone into medicine, just on a different field: that of extending the longevity of the human race, by stopping or even rewinding the internal clock within our cells. He is in Amsterdam to meet fellow researcher Dr. Paul Linden. Initially, it seems Linden is “off,” but Ben doesn’t appreciate how much until he comes across the dangling corpse of his colleague, Linden having hung himself. Paul decides to stay on, and gets permission to continue Linden’s research, which appears to have succeeded in doubling the lifespan of laboratory mice. However, there are significant and suspicious gaps in the research papers.

The further Paul digs, the more he discovers that all was not well in Linden’s life. He was having a sadomasochistic affair with a younger woman, Anna (Aumont), the upkeep of which was putting him under financial stress. As a second source of income, he had agreed to work as a consultant for a Swiss pharmaceutical company owned by Nicholas Ulrich (Kinski). This had given him access to papers smuggled out of the Soviet Union, and led to Linden moving from experimenting on mice, to the residents of an old folks’ home nearby. The results could charitably be described as “mixed”. One resident basically regains the flower of youth; quite a few more don’t survive the treatment.

The longer Paul stays in Amsterdam, the more it seems he is inevitably going down the same path as Linden. He begins a similarly bondage-heavy relationship with Anna (which probably explains why the BBFC-approved version passed in 1987 and 1995, runs a terse 77 minutes!). Through her, he is also introduced to Ulrich, who makes the same offer of employment he made to Linden. Paul’s efforts to investigate the survivor at the old folks’ home also go wrong, forcing him deeper into cahoots with the increasingly suspicious industrial magnate. It all ends in an annoyingly open manner, with Paul going to Ulrich’s facility in the Swiss Alps, but not exactly committing to give his boss the gift of eternal life.

As mentioned, there were points where it did seem to be trying to say something about identity as well as the tension between scientific progress and larger concerns. If we could suddenly live forever, what impact would that have on society? Would it be worth the cost? There are some interesting topics for discussion there, though the film never does much more than skate across their surface. There were also times where it felt like a predecessor to David Cronenberg’s Videodrome. The combination of cutting-edge technology, sexual deviance and the gradual loss of identity are all topics with which Cronenberg is familiar, though he handled them with much greater confidence and coherence than the director here. Whitelaw, who was best known as a subtitler, only directed one other feature, 1997’s Vicious Circles.

As for Kinski, this is not one of his more memorable performances, and to be honest, my attention was hard-pushed to remain engaged until he does more than lurk menacingly in the background. That comes in the second half, in particular after he engages with Paul, and attempts to get his hooks into the young researcher. It’s clear Ulrich is thoroughly unconcerned with anything getting in the way of his desire to live forever. Probably nothing makes this clearer than his purchase of a mask used to perform Faust for the Nazis (that’s particularly unsubtle!). He then dons it while going down on Anna, getting whiny after Paul phones him up during their sex play: “Now I’ve lost my concentration!”

On working with Klaus (for the second time, after Pride and Vengeance), Aumont said, “He was quite calm. I read his biography and I do not like what he says of me, the “pétite Aumont, la pétite Marquand”, when he says that he preferred to go elsewhere rather than the “orgies of the pétite Marquand” or something like that. What do I know, he will have written it because of my reputation for using opium Our relationships were good, we ate together a thousand times. Pretty hypocritical.” It is true that Aumont had a long history of drug abuse, spending nine months in jail for importing opium after being arrested in 1978. However, the above seems odd, since – at least in the English translations – neither All I Need is Love nor Kinski Uncut include any such reference.

In the DVD commentary, director Whitelaw has some kind things to say about Kinski, though he did apparently complain about the smell of the mice! “He was extremely nice on the film. He said we had such good food because we had cheeses and cold cuts for lunch. I mean, he wasn’t there for that long but he was not at all bad. He was very nice to work with. I had always loved Klaus Kinski.. I got in touch with Kinski and he was available and he was not very expensive; he keeps on saying, “I was a whore, I would have done any movie, anything, for the money and they paid me”, but in fact, he got very little money. He was extremely nice on the set.” In typical Klaus style, he did make unilateral changes to his character’s dialogue – “I just managed to get what I needed,” says Whitelaw – and the director had to get of a strong Mexican accent Klaus affected on arrival. But compared to many film-makers, Whitelaw seems to have got off lightly.