Dir: George Roy Hill

Star: Diane Keaton, Yorgo Voyagis, Klaus Kinski, Sami Frey

Based on a novel by renowned British author, John Le Carre, this is story of Charlie (Keaton), a young and idealistic actress who is recruited by Mossad, the Israeli intelligence arm, despite her own, strongly pro-Palestinian views. Under the control of Martin Kurtz (Kinski), she is seduced by Joseph (Voyagis) and becomes part of the Mossad plot to locate and target Khalil (Frey). He’s a Palestinian bomb-maker, whose devices have already resulted in many deaths. Charlie will play the girlfriend of Khalil’s younger brother, who has already been captured by Mossad, in order to get close to the subject. But even for an actress, taking on such a role comes with a terrible emotional cost, as Charlie discovers.

The general consensus appears to be that the film is not a very good adaptation of the book. According to Roger Ebert, it “lacks the two essential qualities it needs to work: It’s not comprehensible, and it’s not involving. They made a real effort to pull off the daunting task of filming John Le Carré’s labyrinthine bestseller, but the movie doesn’t work.” I haven’t read the book, so can’t comment on that aspect, but on its own terms, the film does seem to be considerably lacking on the motivation front. In particular, for someone apparently so fervently devoted to the Palestinian cause, Charlie’s conversion into an agent for their greatest enemy is neither credible nor convincing. Her relationship with Joseph falls some way short of authenticity either.

It’s not the first time that director Hill seemed to struggle with the process of adapting a well-respected literary work to the big screen. While he had great popular and critical success with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting, his efforts to translate novels into movie were much less noteworthy. Neither Slaughterhouse-Five and The World According to Garp have endured as well, and Girl likely should be filed in the same drawer. It’s the flaws with the central characters which were the largest problem, and perhaps inevitably, when you try to distill a 500-page, densely-packed book down into a couple of hours, something has to give, somewhere. It doesn’t appear to have been the plot, of which there’s more than enough.

I did find it admirably even-handed. There have been plenty of other films which covered the undercover war between Mossad and their terrorist adversaries in the wake of the Munich massacre, but these have generally leaned more heavily toward the Israeli viewpoint. This is more neutral, and certainly considerably more cynical in its approach. Both sides have no qualms at all about using and deceiving people to achieve their ends, and it’s fortunate the script follows the novel to its downbeat conclusion. where Charlie is basically broken by the mission, and the realization she has been utterly played as a patsy by Kurtz and his crew.

I did find it admirably even-handed. There have been plenty of other films which covered the undercover war between Mossad and their terrorist adversaries in the wake of the Munich massacre, but these have generally leaned more heavily toward the Israeli viewpoint. This is more neutral, and certainly considerably more cynical in its approach. Both sides have no qualms at all about using and deceiving people to achieve their ends, and it’s fortunate the script follows the novel to its downbeat conclusion. where Charlie is basically broken by the mission, and the realization she has been utterly played as a patsy by Kurtz and his crew.

The film is also on considerably better ground when working as a “spy procedural” depicting the nuts and bolts of clandestine operations, and the convoluted lengths to which organizations will go. [You’ll never trust a detour sign again] For example, there’s a very well-crafted and interesting sequence where Charlie is dropping off a car in a European town, before catching the train to Munich. The surveillance and counter-surveillance tactics deployed by both sides make for intriguing viewing, as do the lengths gone to fabricate artifacts creating a believable romance between Charlie and Khalil’s brother. On the other hand, the script appears unable to tell the difference between Nottingham and Dorset, a clunky mistake which I’m sure was not made by Le Carre.

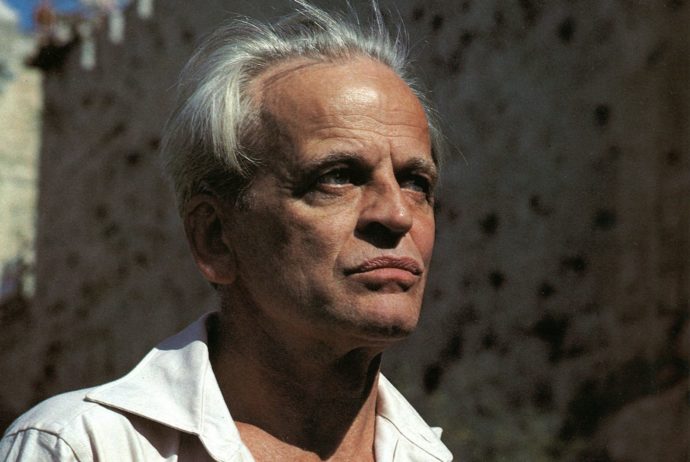

Kinski is on the other side of the coin, having taken the role of a terrorist who hijacks an Israeli plane in Operation Thunderbolt, seven years previously. Though it feels a bit odd to have somebody like Klaus, who fought as part of the Nazi Wehrmacht in World War II (albeit briefly and extremely badly, by his own account!) playing an Israeli. Kurtz makes for a good character – I found him a more compelling figure than Charlie, certainly. He’s a puppet-master who is pulling the strings from behind the scenes – of everyone, in particular of Charlie – with an almost fanatical dedication to the cause, and a ruthless disregard for the consequences to the puppets. Yet he’ll also pause operations to check in with his wife.

His performance received some praise at the time, for example People magazine said Klaus, “steals what there is of the picture. Kinski is pure Le Carré. Keaton is pure Hollywood.” However, Ebert wrote that his performance “seems intended for a standard thriller. There is no sense of the man’s past, of his intelligence, of his torn emotions, of the doubts he has about the job that Charlie is being asked to do.” I’d disagree, with at least some of that. Kurtz comes across as very smart: it feels as if he is playing chess, while everyone else in the film is playing checkers. Except for Charlie, who is struggling to come to terms with the tactical subtleties of noughts and crosses.

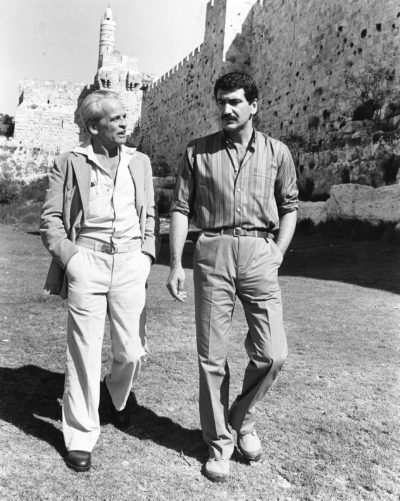

Le Carre also shows up in a cameo, and it was amusing – albeit, probably just to me! – to notice a very young Bill Nighy, playing one of the members of Charlie’s theater company, who is also her boyfriend. This was a full two decades before I first remember noticing him in Shaun of the Dead. At the time of this film’s release, the New York Times wrote it “could have been done successfully as a television mini-series,” amd [erhaps Nighy will also show up in the impending BBC version of the series, due to start filming in 2018. That will be directed by renowned Korean film-maker, Chan-wook Park, who made Oldboy and Lady Vengeance, and a six-part series might be better equipped to handle the densely-packed structure of the source material.