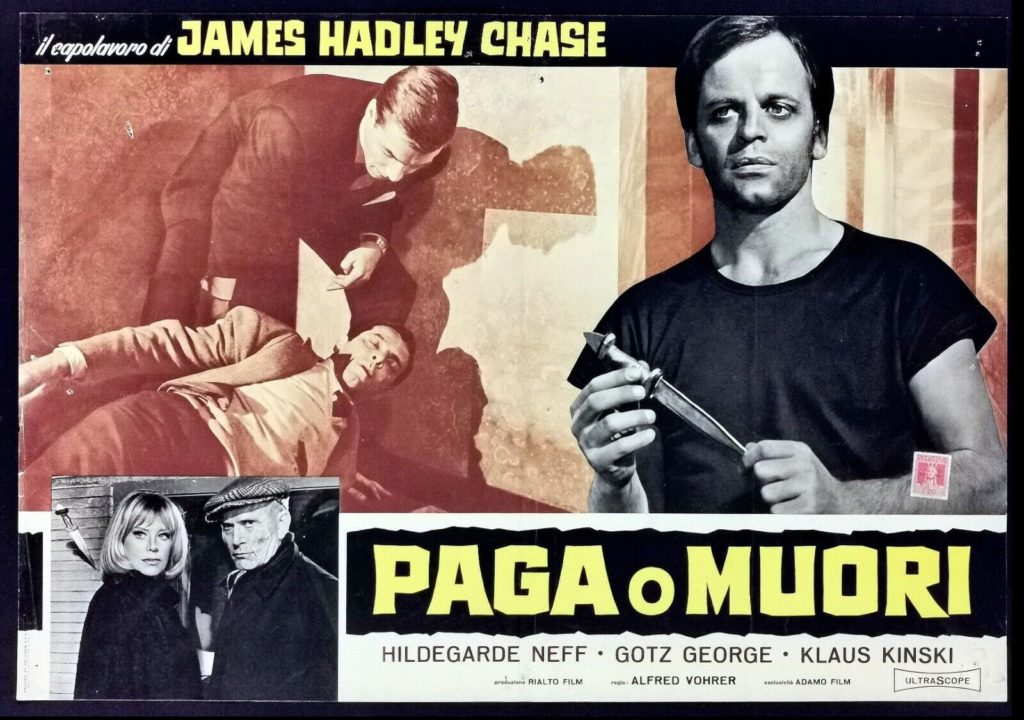

Dir: Alfred Vohrer

Star: Hildegard Knef, Götz George, Richard Münch, Klaus Kinski

a.k.a. Wartezimmer zum Jenseits

“Hier spricht… James Hadley Chase”? Shurely shome mishtake? But that’s the feeling you get here, because this could have been one of the Edgar Wallace krimi movies made by Rialto in the sixties. Not the least element being Vohrer, in particular considering his track record to this point. I think he is probably the man who directed Klaus most often, surpassing even Kinski’s legendary collaborations with Werner Herzog. Vohrer made nine films in which Klaus appeared during the sixties, most of them being Wallace adaptations. Their partnership began with The Dead Eyes of London (1961) and continued until Creature with the Blue Hand (1967). That said, this is likely one of their lighter efforts, with Klaus collecting his check at the thirty-minute mark. We’ll see though, he still leaves a mark.

As suggested above, this was based on a book by Chase, specifically Mission to Siena, which was originally published in 1955, though under another nom-de-plume of Raymond Marshall. [While best known as Chase, that was a pseudonym too, with his real name being René Lodge Brabazon Raymond] It was one of two adaptations of a Marshall novel to come out that year, with Mission to Venice also being released. That may explain the changes in title. The English language one is a little weird: while a tortoise with a skull painted on its back does make an appearance, it’s of trivial significance in the film. The book makes it considerably more clear that it’s the nickname of the chief villain. The German title translates as “Waiting Room to the Beyond”, and is probably a better one.

It begins with Don Micklem (George) getting worrying news from his aunt, telling Don that his rich uncle is the victim of extortion, having received a demand for cash. A refusal to pay will be met with his death. Uncle doesn’t take it seriously, but he should. For it’s part of a scheme by the wheelchair-bound Marchese Mario Orlandi di Alsconi (Münch). He knows the target won’t pay up, and intends to kill him so that future victims will be more inclined to acquiesce to his demands. Sent to London to organize things is his moll, Laura Lorelli (Knef), who arrives to find a disgraced knife-thrower (!) Shapiro (Kinski) has been hired to carry out the hit. Despite Don’s efforts, that’s exactly what happens, but Shapiro is trailed by Don and the authorities to a seedy hotel out of which Laura is operating. He finds evidence linking her to the hit, while Shapiro is silenced to ensure he doesn’t talk to the authorities.

Laura high-tails it out of the country and back to Trieste where the Marchese has his headquarters, a sprawling complex of Bond villain-like complexity. Don follows her to Italy, in search of the truth about his uncle’s death, along with sidekick Harry (Hans Clarin, in a light comic relief role obviously written for Eddi Arent), He appears to have help in the shapely form of Laura, who is seeking a way out of her relationship with the crippled aristocrat, and saves Don from being the victim of a bomb attempt on his life. However, does she genuinely care, or is it merely part of a larger plot? For she tells di Alsconi that Don is the heir to the uncle’s fortune, and his wealth now makes him a target for the Marchese’s scheme. He’s captured and a ransom demanded: can Don talk, work, fight or even love his way out before he becomes superfluous to requirements?

Even allowing for my Kinski bias, I felt this worked considerably better in the first half, with a broader scope of locations and plot development. There is some super location period footage of central London to start (below), and the script does a good job of pitting Laura’s plot against Don’s defensive maneuvers, then his attempts to uncover the murderers. The story-line is relatively straight-forward compared to some of the Wallace films: we know from the start who is responsible, and there are no red herrings to speak of. But once it gets to the Adriatic, and Don is captured, it kinda grinds to a halt. While there apparently was a reasonable budget, the film remains mostly confined inside di Alsconi’s mansion, and the film feels as much a captive as its hero.

The only time the film generates real tension is after the Marquesi discovers Laura’s intentions, and confines her, Don and a couple of minor henchmen in a room with a hydraulic press for a ceiling. Like his lair, it’s high-grade Bond villainy: why bother shooting them when you can create an extended sequence of torment, as they discuss whether to shoot each other before they are crushed to death? There’s uncertainty as to the eventual fate of di Alsconi, and I suspect if this had been a bigger box-office success, he might have been brought back to anchor a franchise [Some other reviews compare this to the Mabuse franchise about an evil criminal mastermind, but I haven’t seen enough of those to comment here]

On the positive side, the performances are generally good. George is a suitably square-jawed hero, and Knef has an ethereal, poignant feel to her performance: Laura feels like a character who wants to be good, but pragmatism has forced her into doing bad things, purely to survive. It’s just a shame Klaus’s twitchy circus performer is not allowed to go deeper into the movie. Even with a relatively small amount of screen-time, it’s a memorable character from his very first scene. There, he demonstrates his credentials to a dubious Laura, by turning the lights out and then immediately hurling a knife, which embeds itself in the wall of her trailer, inches from her head. Point made, both literally and metaphorically. Shapiro is key, in that it is his nervous fleeing to her hotel, which gives Don his first clue as to Laura’s involvement, and thus kicks off the rest of the plot. It’s therefore a good example of Kinski having a small role, yet making a significant impression.