Dir: Werner Herzog

At the end of this documentary, Herzog talks about the death of Kinski, shortly after they had finished shooting Cobra Verde and says, “He had spent himself. He burned away like a comet. Afterwards he was ashes.” Chris was watching this, and she turned to me and quoted exactly the line from Blade Runner I was thinking about: “The light that burns twice as bright, burns half as long – and you have burned so very, very brightly.” [And as an aside, wouldn’t Kinski have been awesome as Roy Batty? Though Rutger Hauer was pretty damn good, of course] It’s an appropriate memorial to Kinski, beginning with footage from Klaus’s performance as Christ, later to surface in its entirety as Jesus Christus Erlöser, and ending with the other side of the man, as he stands quietly with a broad grin on his face, and lets a butterfly flutter on and around him (above).

It’s almost difficult to believe these are the same person, especially for someone like me, who is phlegmatic in nature – I never get particularly high, never get particularly low. The Kinski depicted here seems almost clinically bipolar, capable of great rage but also great affection, even to the same person, with Herzog being present at both ends of the Kinski behavior spectrum. Their relationship was a complex one, and the film is as much a portrait of Werner as Klaus. They first knew each other back in a Munich boarding house, when he was a young teenager, with his family and Kinski tenants in the same building. Herzog describes an incident where the actor locked himself in the bathroom for 48 hours: “In his maniacal fury, he smashed everything to smithereens. The bathtub, the toilet bowl – everything. You could sift it through a tennis racket.”

Yet you also get a clear sense that the myth of Kinski was a carefully constructed facade, even from the earliest days. For example, the idea that Klaus was a “natural” actor is contradicted by another boarding-house story, as Herzog says “You could hear him in his closet, for ten hours non-stop, doing his voice and speaking-exercises.” The same goes with Kinski’s autobiography, which Herzog calls “highly fictitious”, and says Klaus told him, “Werner, nobody will read this book if I don’t write bad stuff about you. If I wrote that we get along well together, nobody would buy it.” This fits in with a fond conceit of mine, that Kinski’s entire reputation, indeed his entire public life, was a massive troll. Perhaps something along the lines of Joaquin Phoenix’s I’m Still Here, right up to and including the sexual abuse allegations leveled by his daughter, Pola, who is in on it all. Or perhaps I’m just in denial a supremely talented actor, can also be such a cunt.

The facet of Kinski and his relationship with women is equally inconsistent. Herzog interviews Eva Mattes and Claudia Cardinale, the co-stars alongside Klaus in Woyzeck and Fitzcarraldo respectively. He warns that Mattes was one of the few women who had anything good to say about Kinski,” but both of the actresses speak in warm terms about him. For example, Mattes says Klaus was “a very professional actor, the most professional I have ever known,” which seems somewhat at odds with other footage, such as the near-endless tirade of Kinski’s, against Walter Saxer, Herzog’s production manager on Aguirre. It might have been enlightening to hear from some of the women who could present the other, darker side of Kinski, though admittedly, at the time this was made, Herzog could have little idea of the accusations to come from Klaus’s own family.

That’s another area which could have done with more exploration. Outside of the boarding-house anecdotes, and a couple of scenes from early Kinski film Kinder, Mutter und ein General, it feels as if Klaus sprung, more or less fully-formed, onto the set of Aguirre. Not a mention, for example, of his work in the sixties when he was a staple of the krimi genre. Also, if you’ve seen Burden of Dreams, then good chunks of this will likely be relatively familiar [You’ll likely also be left thanking dysentery, for saving us from the prospect of a Fitzcarraldo which starred, as originally cast, Jason Robards and Mick Jagger…] If I’ve learned one thing during this project, it’s that there was so much more to Kinski than just his features with Herzog, and the glimpses of this given here e.g. his spoken-word work, the Christ performance, are frustratingly brief.

Still, I guess this does go back to this being about, as mentioned earlier, both Herzog and Kinski; it’s not intended to be a biography of the latter’s entire life, fascinating though that would certainly be. [It would be fascinating to hear from some of the other directors who, like Herzog, worked more than once with Kinski, such as Jess Franco, and hear how they handled the experience]. One thing it does bring out are the similarities between the two, which are undeniable. At one point, someone says to Werner, “You would have also been a good Fitzcarraldo. That’s what you are, in reality,” and you can’t argue with that. There are other elements which feel so excessive the entire thing almost borders on a mockumentary, and again, you have to remind yourself this is not actually the film-making version of This is Spinal Tap.

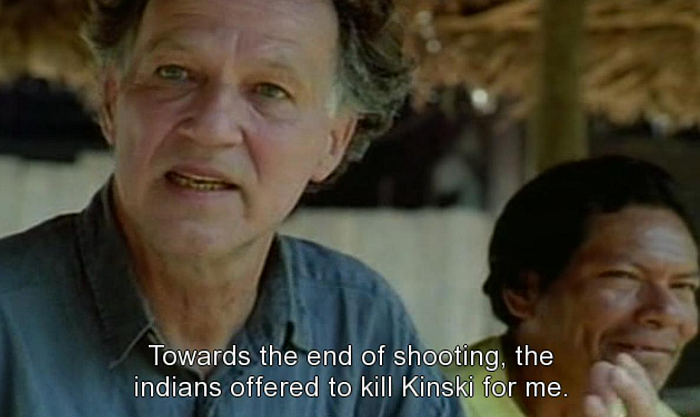

I can’t say I left with any particularly enhanced understanding of the strange, wild man who is the subject of this documentary. If anything, you’ll probably end up being more confused than ever. For even focusing just on the Herzog/Kinski dynamic, we have a relationship where, on the one hand, the director seriously considered the actor’s death on multiple occasions (according to Herzog, “One day I seriously planned to firebomb him in his house. This was prevented only by the vigilance of his Alsatian shepherd”). Yet, on the other, I defy anyone to look at the footage it includes of them together at the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado, and see anything except two artists with a deep respect for each other. There has likely never been another relationship like this in the history of cinema, and we are all enriched by it.