Dir: Sergio Corbucci

Star: Jean Louis Trintignant, Klaus Kinski, Frank Wolff, Vonetta McGee

Damn. This is less of a Western than an anti-Western, turning many of the typical tropes of the genre on its head, from the basic setting through the characterizations of good and evil. And it works, to a remarkable extent, with the results capable of standing beside the very best of the genre, such as Leone’s Fistful trilogy. In particular, the ending is amazingly downbeat: you can’t possibly discuss the film without talking about it, and spoilers will inevitably ensure. I’ll tag those, but if you have not already seen this, go and do so first. I’ll wait here, and you can thank me later.

Right from the beginning, it’s clear this is not a normal Western, or even a normal spaghetti Western. Rather then the usual hot, dusty deserts, with Spain standing in for America, it takes place against a white, snow-covered backdrop: supposedly Utah in 1898, two years after the state was founded, but filmed in the Italian Dolemites. Even though it wasn’t shot in one of the super widescreen formats – it’s 5:3 ratio – there is still something of Lawrence of Arabia about the way cinematographer Silvano Ippoliti shot this. In particular, the way people are often dwarfed by the immensity of the landscape emphasizes their isolation. The chilly climate is also in line with the emotionless approach: there’s little warmth to be found in the characters or their actions.

It also reverses the usual roles. In most Westerns, the bad guys are the people whose faces are to be found on the ‘Wanted’ posters. But in The Great Silence, the outlaws are the victims. While it’s unclear exactly how this happens, it appears they have been unjustly targeted by Pollicutt, a local banker played by Luigi Pistilli. Corbucci remains vague on the details – perhaps because it would weaken the political point he wants to make about exploitation of the working class. One victim’s wife is told, Policutt “wouldn’t give your husband any work and forced him to rob.” I’d be inclined to argue no-one is ever forced into criminal behavior, and people should take responsibility for the consequences of their illegal actions. But maybe that’s just me.

Conversely, the hero in traditional genre entries is likely the man going after them. Not here: pointedly, they are called “bounty killers” rather than bounty hunters. The main such is the appropriately-named Loco (Kinski), who has teamed up with the banker: Pollicutt proposes, Loco disposes, under a thin veneer of both legality and morality. Loco proclaims. “They’re against God, humanity, moral and public order. Killing them is a good thing, believe me.” But there is, literally, a new sheriff in town. Gideon Burnett (Wolff) arrives, appointed by the new state’s first governor to bring an end to the pair’s dubious practice. Though even this is dubious, Burnett believing the governor is merely attempting to curry favor with the voters.

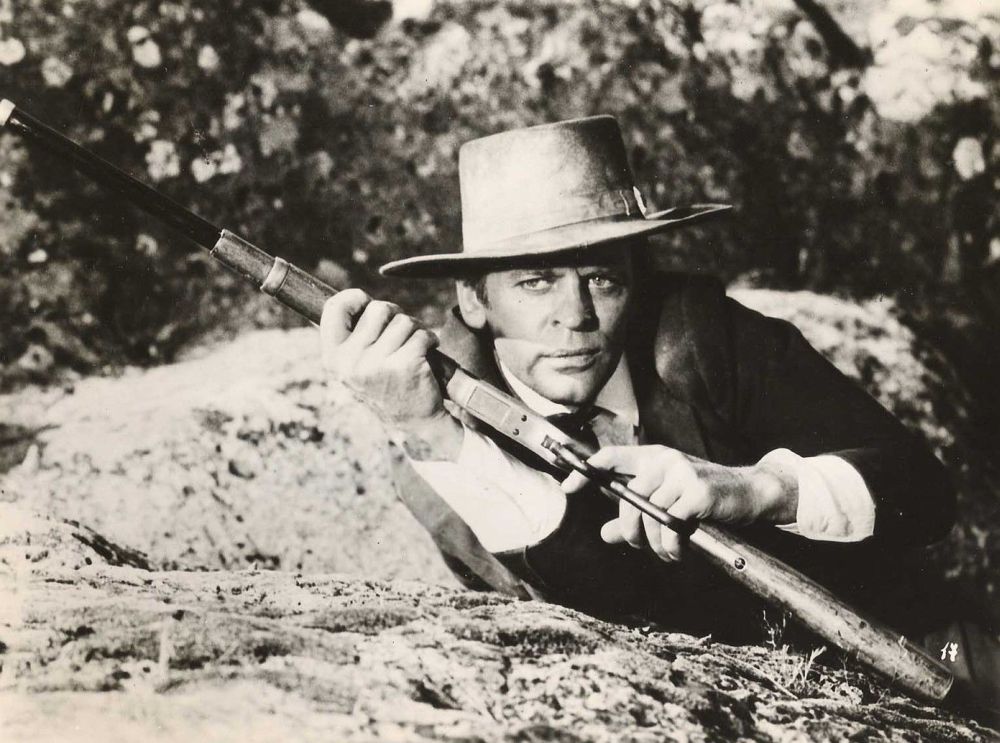

The final side of the film’s quadrilateral is Silence (Trintignant). He watched as a child, when his mother and father were killed by bounty killers under the direction of Policutt. They slit his vocal cords, to stop him from telling anyone what happened, rendering him mute. Though apparently, he is not called Silence due to this, but “Because wherever he goes, the silence of death follows.” Seems a tad over-complicated to me. Anyway, he is now on a relentless mission to exterminate all bounty killers, though does so in a heroic way. He’ll never draw first, which lets Silence claim self-defense and avoid prosecution for their deaths.

These four line up in the remote town of Snow Hill, where citizens with prices put on their head by Policutt have had to flee to the mountains, while Loco picks them off. Silence arrives in town on the same stagecoach as Sheriff Burnett, the latter being forced to hitch a ride after the outlaws ate his horse(!). Our hero is in town due to a letter sent by Pauline Middleton (McGee), whose husband was one of Loco’s recent victims. She tries to raise Silence’s fee by selling her house to Policutt, but he is more interested in another form of payment, shall we say. Silence attempts to provoke Loco, but the bounty killer is aware of the technique and initially refuses to draw.

After a fist-fight, Loco reaches for his gun, but Burnett intervenes and arrests him for attempted murder, much to the displeasure of both Policutt and Loco’s gang. When being taken to prison in Tonopah, Loco escapes and sends the sheriff into a frozen lake. He gathers his men and takes them back into town, first stopping to rape Pauline and badly burn Silence’s gun-hand. The outlaws have come to town in search of food, and are rounded up by Loco’s gang, and held as hostages in the saloon to draw out Silence. The tactic works, and Silence shows up outside the saloon, ready for a final confrontation with his nemesis which is likely the film’s signature scene.

[SPOILERS BEGIN] For in a traditional Western, even though wounded, Silence would shoot down Loco and ride off into the sunset with Pauline. Here, the exact opposite happens, with the bad guys triumphing completely and absolutely. Loco’s gang shoot Silence several times, before he administers the coup de grace. Pauline tries to return fire, but is also gunned down. The gang then massacre all of their hostages, on whom they can collect the bounties. Loco takes Silence’s specialist gun, the then newly-invented semi-automatic Mauser C96 pistol, from Pauline’s hands, and rides off. A caption announces the event “brought forth fierce public condemnation of the bounty killers”. Well, that’s alright then…

It’s easy to understand why, when the film was screened for Darryl Zanuck of 20th Century Fox, the ending allegedly made him swallow his cigar, and he refused to distribute it in North America. The Italian producers were similarly concerned, and to appease them Corbucci shot a radically different alternate ending. In this, Bennett turns out to have survived his icy dip, and rides to the rescue at the last minute. Together with Silence – whose hand is protected by an iron gauntlet – they kill Loco and his henchmen. Burnett then asks Silence to become a deputy, which he accepts with a broad smile, in sharp contrast to his taciturn demeanor over the rest of the film. It’s much more in line with Western tropes, and thus appears to have strayed in from a completely different movie.

Certainly, in its original form this has to be considered one of the bleakest films, not just in the Western genre, but of any. Few end with the side for which the audience has been rooting throughout, getting defeated in such a complete manner. Yet, you’d be hard pushed to argue this comes as much of a shock. Or, at least, it shouldn’t, unless you put greater weight to the standards of the genre than the signals Corbucci has been giving throughout his film. For the cynicism on view is clear, with even Silence acting here partly out of a desire for personal vengeance, partly for mercenary reasons (he quotes Pauline a $1,000 fee for killing Loco). Justice seems barely to enter the picture. [SPOILERS END]

Corbucci didn’t hide his left-wing sympathies in any of his films, and this is basically an allegory for the greed of capitalism, and how it grinds up and abuses people in pursuit of profit. While not my view, it’s one I can appreciate, because this works as cinema, regardless of whether or not you agree with it. The director was also inspired by 1960’s figures like Martin Luther King, Che Guevara and Malcolm X, who were prepared to take on the state in support of their beliefs. The movie also gets great support from Ennio Morricone’s score, which is surely among his best. It’s a shame the possibilities this demonstrates for the Western genre weren’t developed by other film-makers.

It’s definitely one of Kinski’s finest characters, though may be a little too restrained to be considered among his finest performances. In my opinion, he’s always at his best when there’s a sense of underlying insanity, bubbling just below the surface. For despite his name, fondness for violence and odd taste in attire, wrapping himself in a woman’s shawl, Loco is restrained and smart, as well as adept at pushing other people’s buttons, whether for advantage or merely his own amusement. Take, for example, his response after being introduced to the currently equineless Burnett as the sheriff. “So I gather from your star. I thought you sold horse-meat. But with that on, you look more like a sheriff – who sells horse-meat.”

Kinski was with his wife and daughter during the shoot, and wrote about the experience in his autobiography:

In Cortina d’Arnpezzo, I make the first snowbound Western. Biggi and Nasstja are happy and cheerful; they frolic in the snow, go sledding all day, skating, and ride jingly, horse-drawn sleighs to the mountains. But the instant I’m alone with Biggi, we argue and hit one another. This time the reason is the black American actress Sherene Miller [clearly Vonda McGee, and she is named as such in the All You Need is Love edition], who’s also starring in the movie. She’s got a boyish body, boyish haircut, boyish ass, and almost no tits. Her room lies directly over our apartment. In the morning, when I come back after fucking Sherene half the night, I sneak past a sleeping Biggi to get my toothbrush, razor, and fresh underwear. This way, we can’t fight. I kiss her and Nasstja cautiously, to avoid waking them.

Kinski Uncut, p.191

However, shooting apparently wasn’t quite as placid as Klaus’s account would appear to indicate. According to Corbucci (via Wikipedia), Wolff had to be restrained from strangling Kinski when the latter insulted his Jewish heritage by telling him “I don’t want to work with a filthy Jew like you; I’m German and hate Jews.” Following the incident, Wolff refused to speak to Kinski unless required to by the script. Kinski later declared that he insulted Wolff because he wanted to help him get into character. They would appear to have made up, at least on a professional level, as Kinski and Wolff would go on to work together again, on another spaghetti Western the following year, Sartana the Gravedigger.

This is one of the films where Kinski’s character is not the focus, yet is essential to the plot. It’s Hagan’s actions that set things in motion, although at the bottom level, there isn’t much moral difference between him and Hamilton: both want revenge for the death of family members, and to kill those responsible. Despite this mirroring of motivation and action, there’s no doubt who’s the good guy and who’s the villain, as far as the film is concerned. Fidani is firmly in the Kid’s corner, portraying his vengeance as “righteous”, unlike Hagan’s. It’s an interesting double-standard. Perhaps it’s that Hagan is seen to be acting out of rage, while Hamilton’s response feels measured, more like justice is being meted out. We also know he’s correct in his choice of target: we never see who was behind the death of Hagan’s brothers.

This is one of the films where Kinski’s character is not the focus, yet is essential to the plot. It’s Hagan’s actions that set things in motion, although at the bottom level, there isn’t much moral difference between him and Hamilton: both want revenge for the death of family members, and to kill those responsible. Despite this mirroring of motivation and action, there’s no doubt who’s the good guy and who’s the villain, as far as the film is concerned. Fidani is firmly in the Kid’s corner, portraying his vengeance as “righteous”, unlike Hagan’s. It’s an interesting double-standard. Perhaps it’s that Hagan is seen to be acting out of rage, while Hamilton’s response feels measured, more like justice is being meted out. We also know he’s correct in his choice of target: we never see who was behind the death of Hagan’s brothers.

The focus is, instead, on Macho Callaghan (Cameron) – note the “g”, for legal reasons! – who is the sole survivor of the Carson gang, after they are attacked and massacred by Butch Cassidy (Betts) and his gang. After recovering, Callaghan teams up with another renegade, Buck O’Sullivan, to take revenge on the people responsible – a process complicated by Cassidy’s group having split in two, with Buck among the men now following Ironhead Donovan (Mitchell). Those two parties hold no love for each other either, having split after a rigged game of poker. The vast bulk of the running time sees Callaghan and O’Sullivan working to infiltrate Ironhead’s gang, and/or attack Cassidy’s. It’s all incredibly dull, even by the low standards of Fidani, whose reputation as among the worst of spaghetti Western directors is certainly not diminished by this.

The focus is, instead, on Macho Callaghan (Cameron) – note the “g”, for legal reasons! – who is the sole survivor of the Carson gang, after they are attacked and massacred by Butch Cassidy (Betts) and his gang. After recovering, Callaghan teams up with another renegade, Buck O’Sullivan, to take revenge on the people responsible – a process complicated by Cassidy’s group having split in two, with Buck among the men now following Ironhead Donovan (Mitchell). Those two parties hold no love for each other either, having split after a rigged game of poker. The vast bulk of the running time sees Callaghan and O’Sullivan working to infiltrate Ironhead’s gang, and/or attack Cassidy’s. It’s all incredibly dull, even by the low standards of Fidani, whose reputation as among the worst of spaghetti Western directors is certainly not diminished by this.

The interplay between these factions and individuals is always intriguing. Hogan in particular is a wild-card, liable to explode into sudden brutality at the drop of a card. Yet that appears to make him something of a chick-magnet. One of the hostages basically flings herself at him, resulting in this immortal exchange between her and Hogan:

The interplay between these factions and individuals is always intriguing. Hogan in particular is a wild-card, liable to explode into sudden brutality at the drop of a card. Yet that appears to make him something of a chick-magnet. One of the hostages basically flings herself at him, resulting in this immortal exchange between her and Hogan:

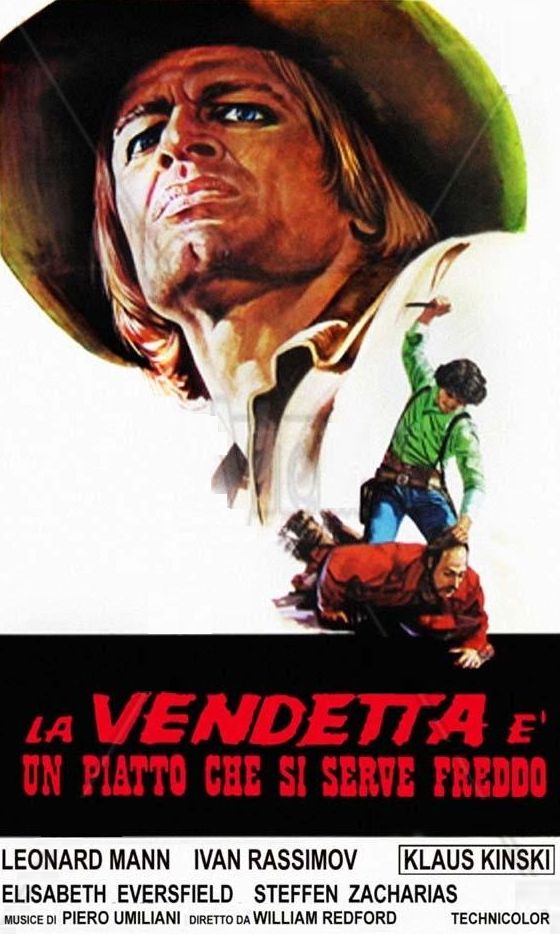

Jeremiah heads off Boone and his men on their way to carry out the attack, frees the tribesmen whose corpses are intended to be left at the scene, and heads back to infiltrate his way into Perkins inner circle. For this is where the Italian title comes into play: it translates as “Revenge is a dish best served cold.” And there I was, thinking all the time it was a Klingon proverb. Quentin Tarantino was lying to me! [And it’s not as if a film geek like QT, especially one so devoted a fan of spaghetti Westerns, would be unaware of this one, though the phrase pre-dates the movie, obviously] So, ten years on, it’s time for those who were really behind the murder of our hero’s family, to pay for their crimes.

Jeremiah heads off Boone and his men on their way to carry out the attack, frees the tribesmen whose corpses are intended to be left at the scene, and heads back to infiltrate his way into Perkins inner circle. For this is where the Italian title comes into play: it translates as “Revenge is a dish best served cold.” And there I was, thinking all the time it was a Klingon proverb. Quentin Tarantino was lying to me! [And it’s not as if a film geek like QT, especially one so devoted a fan of spaghetti Westerns, would be unaware of this one, though the phrase pre-dates the movie, obviously] So, ten years on, it’s time for those who were really behind the murder of our hero’s family, to pay for their crimes.