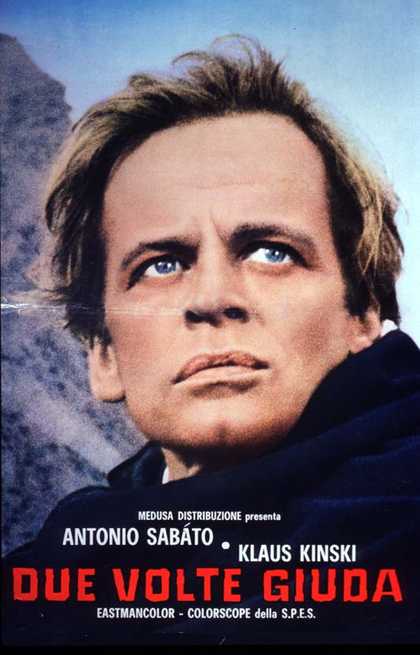

Dir: Nando Cicero

Star: Antonio Sabato, Klaus Kinski, Narciso Ibáñez Menta, Cristina Galbó

a.k.a. Due volte Giuda (Twice a Judas)

This is a strikingly good idea, which grabs the viewer’s interest right from the get-go. A man (Sabato) regains consciousness on the side of a hill, next to a corpse. He can remember nothing about who he is, or how he got there. Making his way to the nearest town, he’s recognized as Luke Webster by someone, who appears to have a job for him. Our hero plays along, even when he discovers he’s going to be the decoy at an assassination of a local landowner. Except, he then discovers the victim is actually his brother, Victor (Kinski). Why did he agree to be part of such a plot? If only he could remember the past… From here unfolds a tale of filial tension, local politics and vengeance, as Luke seeks the man responsible for killing his wife, whose name, “Dingus”, is carved into the butt of Luke’s gun. [The film claims it’s also Mexican for “mongrel” or “half-breed”, which makes sense in the light of what transpires, but I haven’t found any verification for this] For it turns out that this hit on Victor was put out by a group of local bankers led by Murphy (Menta): there’s a fierce struggle between them over local tracts of land, with both sides using intimidatory tactics to try and bend the homesteaders to their will.

This is a strikingly good idea, which grabs the viewer’s interest right from the get-go. A man (Sabato) regains consciousness on the side of a hill, next to a corpse. He can remember nothing about who he is, or how he got there. Making his way to the nearest town, he’s recognized as Luke Webster by someone, who appears to have a job for him. Our hero plays along, even when he discovers he’s going to be the decoy at an assassination of a local landowner. Except, he then discovers the victim is actually his brother, Victor (Kinski). Why did he agree to be part of such a plot? If only he could remember the past… From here unfolds a tale of filial tension, local politics and vengeance, as Luke seeks the man responsible for killing his wife, whose name, “Dingus”, is carved into the butt of Luke’s gun. [The film claims it’s also Mexican for “mongrel” or “half-breed”, which makes sense in the light of what transpires, but I haven’t found any verification for this] For it turns out that this hit on Victor was put out by a group of local bankers led by Murphy (Menta): there’s a fierce struggle between them over local tracts of land, with both sides using intimidatory tactics to try and bend the homesteaders to their will.

The main problem here, is the usual one concerning cinematic amnesia. It’s an obvious and contrived gimmick, with the victim inevitably recovering their memory in the way and at the time which is necessary for the dramatic goals of the movie. In this particular case, it’s triggered by Luke’s discovery of a music-box, resulting in a flashback that more or less ticks all the boxes, and sets up the final showdown. There, we just know he’s going to showcase off his father’s weapon, a modified shotgun that sends a spray of lethal missiles over about a 60-degree arc in front of the shooter. However, to get there, he has to withstand a lethal assault at the family homestead where his mother is still living. Fortunately, the family dog still remembers him, and his happy to assist by flushing the enemy up from their hiding places, for Luke to take down.

Still, despite my qualms about the convenience of the plotting, this is still delicious in its moral ambiguity. For much of the running time, you had little or no idea about who was good or bad, since nobody seemed to have an unassailable moral position. Vincent, for example, firmly believes he’s on the side of the angels – except, the way he behaves is in reality, little or no different from the bankers he’s fighting. Is he really liberating the Mexican peons who are being deported? Or simply ensuring his property has cheap workers? That even extends as far as the hero, who shows an early willingness to take part in murder for hire, and only has moral qualms when he discovers the target is a blood relative. Hell, for a good chunk in the middle, I had a suspicion that he’d actually end up being “Dingus” himself. For example, that name could have been carved into the rifle to indicate his ownership, not as some kind of mnemonic device so he’d remember it. Would have made this an earlier ancestor of Memento had that actually been the case.

Sabata and Kinski are both excellent in their roles, though it might have been even better had the two men swapped their roles, just to confound moral expectations even further. The body count is quite hefty, though it seems at times that Luke is the only person capable of hitting his target: this incompetence is likely necessary to the plot, I think. I hadn’t heard of Cicero before, but it turns out the director was initially an actor, working for the likes of Visconti and Rossellini. This was the last of his three spaghetti Westerns, after Last of the Badmen and Professionals for a Massacre, both starring George Hilton. in the seventies, he switched to the comedy genre, in particular, the bawdy style of the commedia sexy all’italiana. Kinski and Sabato, meanwhile, would face off again a couple of years later, in 1971’s L’occhio del ragno, though it’s not a Western, but a crime film about the aftermath of a diamond heist.

It’s an effective piece of work, ranking in the upper tier both among Kinski’s performances during this era, and of spaghetti Westerns in general. Despite my qualms about amnesia as a plot point, it’s a good deal more restrained and less lazy than some of the others which I have seen try to use the condition, and the other aspects of the storyline, along with the performances, are enough to make me forgive this.