Dir: Werner Herzog

Star: Klaus Kinski, Paul Hittscher, Huerequeque Enrique Bohórquez, Claudia Cardinale

As an appetizer, we watched Les Blank’s documentary, Burden of Dreams, which chronicles the early stages of filming, from the initial attempts with Jason Robards as Fitzcarraldo and Mick Jagger (!) as his sidekick, through the initial camp, burned to the ground by disgruntled locals, and on through the reshoot after Robards came down with amoebic dysentery and Jagger went off to tour. Not that this exactly went swimmingly, as the shoot continued to present problems: the bulldozer used to clear the way needed parts flown in from Miami, there were delays due to attacks from another tribe up-river, and this is probably one of the few films with whores officially on the payroll [Charlie Sheen movies don’t count].

What that film brings out are perhaps the similarities between Herzog the director and Fitzcarraldo the subject, both consumed with an idea that many would conceive as ludicrous, and determined to plough on with it, whatever the cost. You can visibly see Herzog disintegrate over the course of filming, though it’s disappointing that the documentary stops before the director succeeds in pulling off the ‘money shot’ of seeing a 300-ton boat pulled up a forty-degree hill. It’s almost as if Blank is more interested in failure than success, though it’s still worth seeing, purely for Herzog going off on a rant about the jungle:

Kinski always says it’s full of erotic elements. I don’t see it so much erotic. I see it more full of obscenity. Nature here is vile and base. I wouldn’t see anything erotical here. I would see fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and just rotting away… The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery. I don’t think they – they sing. They just screech in pain… It’s like a curse weighing on an entire landscape. And whoever… goes too deep into this has his share of this curse. So we are cursed with what we are doing here… We have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery.

Crack open those Joy Division LPs, folks. What the documentary does soft-pedal, is the stormy relationship between Kinski and Herzog. While perhaps not as bad as during Aguirre, Herzog subsequently said that the natives who were part of the cast, offered at one point to kill Kinski, so disturbed were they by his anger. Werner, however, had learned that letting Klaus’s fury burn itself out was more productive than trying to engage his star. Some of this tactic can been in the footage below, from My Best Fiend, which shows what happens when Kinski goes off. All Blank shows, is Kinski growling about the ‘fucking stinking’ camp, so one wonders why Blank chose to relegate to an out-take, this outburst…

That said, Kinski probably smiles more here than he did in almost any other of the 200+ movies in which he appeared, which is an unnerving sight. He plays opera lover and former railway engineer Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, known locally as Fitzcarraldo, who wants to bring Enrico Caruso to the jungle. To raise money, he spots an opening in the rubber business: a tract of land left unexploited because of the rapids which prevent a boat from going upstream far enough to reachi it. Fitzcarraldo sees that it might be possible to take a nearby river to a point where only a relatively short stretch of hilly country separates it from the river he wants to reach. Haul your boat over that hill, and you can then use it to harvest its rubber.

As noted, it hard to say what’s madder: Fitzcarraldo’s plan, or Herzog’s plan to re-enact it without miniatures, CGI or blue-screen, instead opting to drag a full-scale boat over a 100% actual hill [while inspired by a true story, the real boat was both one-tenth the size, and dismantled into pieces]. On the way, he loses most of his crew, who are unnerved by the local tribesmen, but gets another crew in the shape of said tribesmen, after countering the tribal drumming with his gramophone and opera records. [The resulting audio mash-up is like Caruso jamming with Adan & the Ants.] Fortunately, they have a myth about a white god and his ship, and Fitzcarraldo convinces them that dragging his boat over the hill is part of that. Unfortunately, it’s only part of that…

You often hear of life imitating art, but it’s these parallels between the movie and the making of the movie that give this such resonance: rarely have the two been so close. Both Fitzcarraldo (as played by Kinski) and Herzog (as portrayed by Herzog) are dreamers, obsessed with the grandest of meaningless gestures. They are both prepared to go to any lengths, and make any sacrifice, to achieve their goal, even when simpler means of achieving the same ends would suffice. You can only admire the tenacity, at the same time as you shake your head at the folly – then there’s a scene, where Fitzcarraldo and crew are up a tree, looking at the scope of what they have to do, and you appreciate exactly why Herzog went the extra 1,500 miles or so.

Outside of Kinski, there aren’t much in the way of performances – nobody is given much to do, except trail around the jungle in Fitzcarraldo’s wake. These aren’t so much supporting characters as superfluous ones, but it doesn’t matter much. This is the kind of film that should be in the dictionary beside the word “auteur,” because it’s clear that this was made by a man driven by a vision, rather than, as we so often see these days, the lure of a paycheck.

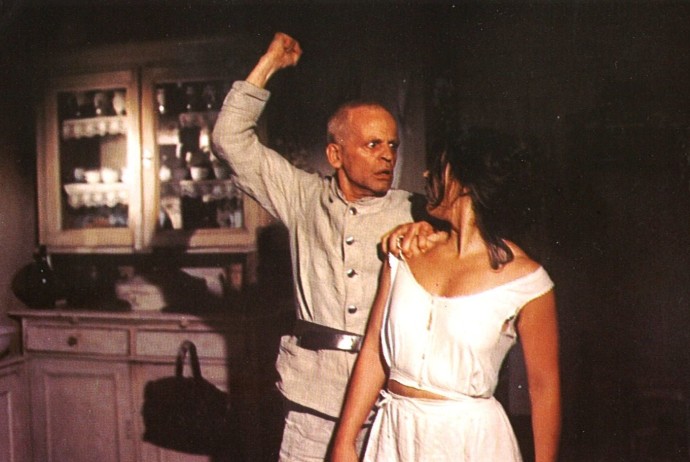

The tipping-point, however, is the realization that Marie may be having an affair with another soldier, higher in rank and – let’s be honest – physical appeal, charm and sanity, while he’s at it. This sends Woyzeck right over the edge, and he stabs her to death while they’re out on a walk. He takes refuge in a local inn, though his blood-stained appearance gives him away. The film ends with the discovery of Marie’s body, and a final caption, stating that it’s been some time since they’ve had such a good murder. I suppose this is some kind of spoiler, but it’s in such little doubt that this is where the movie is heading, that it barely counts.

The tipping-point, however, is the realization that Marie may be having an affair with another soldier, higher in rank and – let’s be honest – physical appeal, charm and sanity, while he’s at it. This sends Woyzeck right over the edge, and he stabs her to death while they’re out on a walk. He takes refuge in a local inn, though his blood-stained appearance gives him away. The film ends with the discovery of Marie’s body, and a final caption, stating that it’s been some time since they’ve had such a good murder. I suppose this is some kind of spoiler, but it’s in such little doubt that this is where the movie is heading, that it barely counts.

It is, very much, a loving homage to F.W. Murnau’s original, though the expiration of copyright allows Herzog to use the actual names of the characters, rather than, as Murnau did, make them up in a (failed) attempt to avoid a lawsuit. The make-up is almost identical, not just on the vampire, but on Lucy Harker (Adjani), who has the same pasty-pale pancake on her face and perpetually-concerned expression as Ellen Hutter in the original – see the illustration on the left. Indeed, sometimes the only way to tell her and Dracula apart is to look for the pointy teeth.

It is, very much, a loving homage to F.W. Murnau’s original, though the expiration of copyright allows Herzog to use the actual names of the characters, rather than, as Murnau did, make them up in a (failed) attempt to avoid a lawsuit. The make-up is almost identical, not just on the vampire, but on Lucy Harker (Adjani), who has the same pasty-pale pancake on her face and perpetually-concerned expression as Ellen Hutter in the original – see the illustration on the left. Indeed, sometimes the only way to tell her and Dracula apart is to look for the pointy teeth.