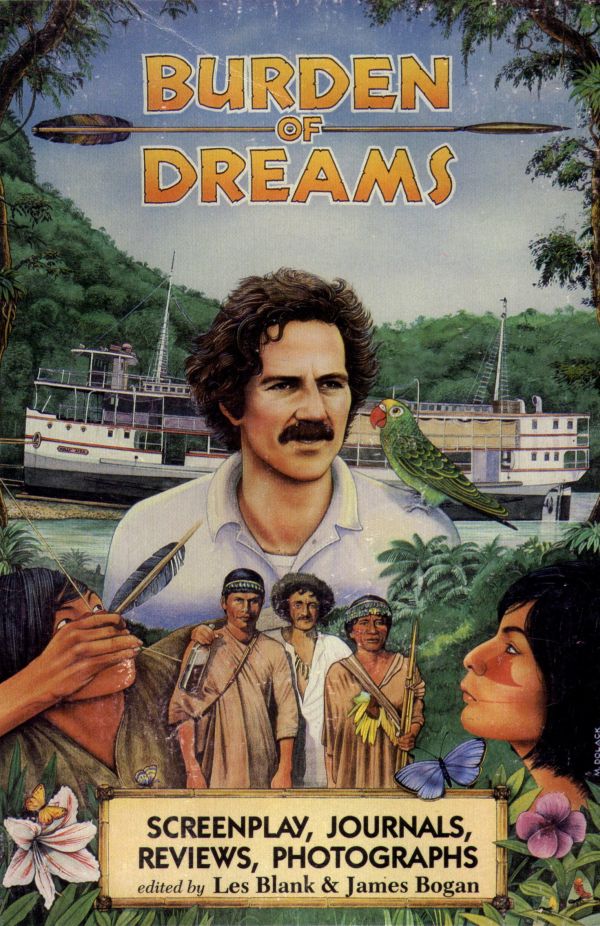

Dir: Les Blank

Star: Werner Herzog, Klaus Kinski, Claudia Cardinale, Thomas Mauch

When you get a chance, google “Werner Herzog motivational posters.” It’s a meme which combines quotes from our favorite dour German director, with beautiful images of nature and life. You get the sense this documentary about the making of Fitzcarraldo may have been the source of many. For, while the relationship between Kinski and Herzog was often… Well, let’s go with a severe understatement and say, “somewhat strained,” what you’ll take away from this is that Klaus was hardly the biggest problem, in a film that took almost four years to complete. It’s just horribly fascinating to watch Herzog disintegrate as his dream collapses around him, eventually launching into the following glorious tirade, a defeated man who is both cursing his opponent, and acknowledging its inevitable superiority. [I see I also included it in the Fitzcarraldo review, but make no apology for including it here as well!]

Kinski always says it’s full of erotic elements. I don’t see it so much erotic. I see it more full of obscenity. It’s just – Nature here is vile and base. I wouldn’t see anything erotic here. I would see fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and just rotting away. Of course, there’s a lot of misery. But it is the same misery that is all around us. The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery. I don’t think they- they sing. They just screech in pain. It’s an unfinished country. It’s still prehistorical. The only thing that is lacking is the dinosaurs here. It’s like a curse weighing on an entire landscape. And whoever goes too deep into this has his share of that curse. So we are cursed with what we are doing here. It’s a land that God, if he exists, has created in anger.

This is a project that was certainly cursed from the beginning, and there’s something appropriate about the film’s subject being a man attempting to do something ludicrous and borderline insane – drag a ship over a mountain – because Herzog’s persistence can only be admired. From the get-go, there were issues with the natives, and the initial location had to be abandoned, with locals burning the camp to the ground as the crew pulled out. Burden also includes footage from the original version, which started filming over a year later with new locations, and starred Jason Robards as Fitzcarraldo, with (of all people) Mick Jagger as his sidekick. After five weeks shooting, almost half the movie was already in the can, when Robards came down with amoebic dysentery and had to return to the United States, where his doctor forbade him from returning. While Herzog tried desperately to find another lead, Jagger had to return to his Rolling Stones related duties, and his character ended up being written out entirely.

This is a project that was certainly cursed from the beginning, and there’s something appropriate about the film’s subject being a man attempting to do something ludicrous and borderline insane – drag a ship over a mountain – because Herzog’s persistence can only be admired. From the get-go, there were issues with the natives, and the initial location had to be abandoned, with locals burning the camp to the ground as the crew pulled out. Burden also includes footage from the original version, which started filming over a year later with new locations, and starred Jason Robards as Fitzcarraldo, with (of all people) Mick Jagger as his sidekick. After five weeks shooting, almost half the movie was already in the can, when Robards came down with amoebic dysentery and had to return to the United States, where his doctor forbade him from returning. While Herzog tried desperately to find another lead, Jagger had to return to his Rolling Stones related duties, and his character ended up being written out entirely.

As we all know, Herzog found a replacement in Kinski, who came to the Amazon jungle for his fourth collaboration with the director – likely triggering memories of the Aguirre shoot. But, in many ways, Herzog was even more maniacally focused here, and his efforts to ensure “authenticity” are beyond the extrene. According to Blank, he “admits he could shoot Fitzcarraldo right outside Iquitos,” a reasonably-sized city in the region. Herzog instead chooses a location that’s a full day into the jungle by air, or two weeks by boat – if reachable at all. He claims “the isolated location will bring out special qualities in the actors, and even the film crew, that would be impossible to achieve otherwise.” It’s clear that Herzog has a vision, and nothing is going to be allowed to interfere with this. Frankly, based on this film, Kinski seems like the sane one in their partnership.

While there were reports of tensions between them, Blank doesn’t provide much on this – the film’s cinematographer, Thomas Mauch, appears more fed-up (and also gets his head cracked open while filming the boat going through the Pongo das Mortes, or “Rapids of Death”). Kinski’s main gripe appears to be the long periods of sitting around, resulting from the lengthy delays in production: the weather proved uncooperative, leaving rivers unnavigable and the bulldozer used to help clear a path for the boat over the mountain was bought second-hand, and kept breaking down, requiring parts to be flown in from Miami. Based on the interview here, it’s the resulting idleness which grated on Klaus’s nerves; curiously, and as hinted at in Herzog’s quote above, Kinski seems to have appreciated the primeval physical location more than most Westerners probably would.

If we would work from the morning to the evening, that’s fine. You have to do something. You have to move, you know. But now we’re just sitting and sitting and sitting around. So you can’t go anywhere. You can’t escape this fucking, stinking camp because you never know when they call you. Because you have to be here because you’re paid for it. You are under contract, so you can’t just go. It means you’re completely captured here. Completely. You go from there to there and from there to there. That’s all that you can do. At least you have this view, instead of something else, and you feel you’re right in the jungle, which is a good feeling, you know.

The main weakness here is likely unavoidable, in that Blank wasn’t there for the finale. It seems he had to leave at a point where completion once again appeared in doubt, with one of the three boats used having run aground and another being stuck at the base of the mountain, all efforts to pull it up having failed. But after the documentarian’s departure, a new engineering crew managed to help Herzog achieve his vision, even if Blank wasn’t there to capture it or Herzog’s reaction. Instead, it ends with the director’s response to being asked what he’d do when filming ends. “I shouldn’t make movies anymore. I should go to a lunatic asylum right away. [It’s] not what a man should do in his life all the time. Even if I get that boat over the mountain and somehow I finish that film, nobody on this earth will convince me to be happy about all that. Not until the end of my days.”

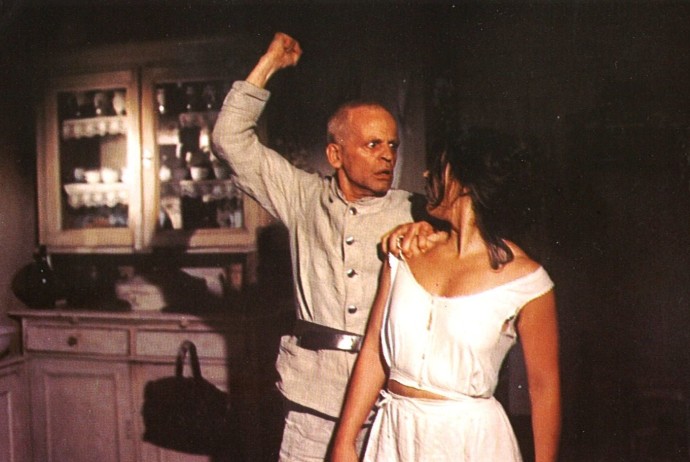

The tipping-point, however, is the realization that Marie may be having an affair with another soldier, higher in rank and – let’s be honest – physical appeal, charm and sanity, while he’s at it. This sends Woyzeck right over the edge, and he stabs her to death while they’re out on a walk. He takes refuge in a local inn, though his blood-stained appearance gives him away. The film ends with the discovery of Marie’s body, and a final caption, stating that it’s been some time since they’ve had such a good murder. I suppose this is some kind of spoiler, but it’s in such little doubt that this is where the movie is heading, that it barely counts.

The tipping-point, however, is the realization that Marie may be having an affair with another soldier, higher in rank and – let’s be honest – physical appeal, charm and sanity, while he’s at it. This sends Woyzeck right over the edge, and he stabs her to death while they’re out on a walk. He takes refuge in a local inn, though his blood-stained appearance gives him away. The film ends with the discovery of Marie’s body, and a final caption, stating that it’s been some time since they’ve had such a good murder. I suppose this is some kind of spoiler, but it’s in such little doubt that this is where the movie is heading, that it barely counts.

It is, very much, a loving homage to F.W. Murnau’s original, though the expiration of copyright allows Herzog to use the actual names of the characters, rather than, as Murnau did, make them up in a (failed) attempt to avoid a lawsuit. The make-up is almost identical, not just on the vampire, but on Lucy Harker (Adjani), who has the same pasty-pale pancake on her face and perpetually-concerned expression as Ellen Hutter in the original – see the illustration on the left. Indeed, sometimes the only way to tell her and Dracula apart is to look for the pointy teeth.

It is, very much, a loving homage to F.W. Murnau’s original, though the expiration of copyright allows Herzog to use the actual names of the characters, rather than, as Murnau did, make them up in a (failed) attempt to avoid a lawsuit. The make-up is almost identical, not just on the vampire, but on Lucy Harker (Adjani), who has the same pasty-pale pancake on her face and perpetually-concerned expression as Ellen Hutter in the original – see the illustration on the left. Indeed, sometimes the only way to tell her and Dracula apart is to look for the pointy teeth.