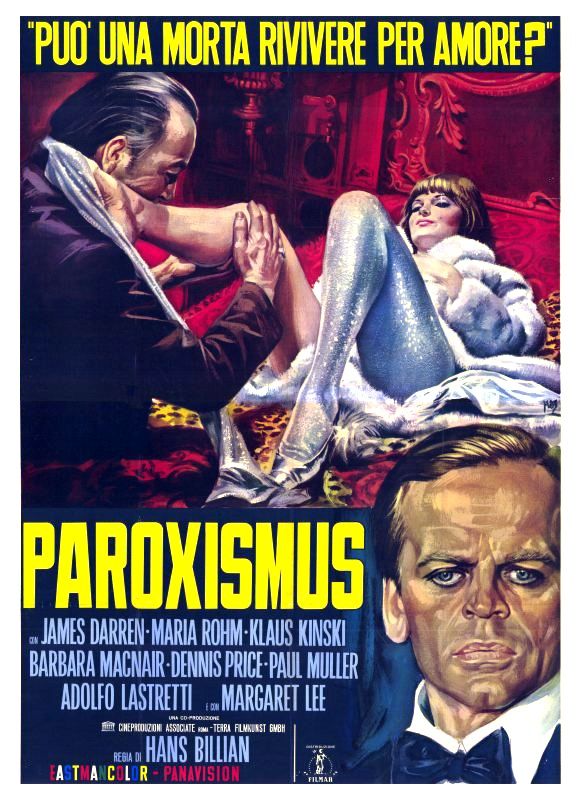

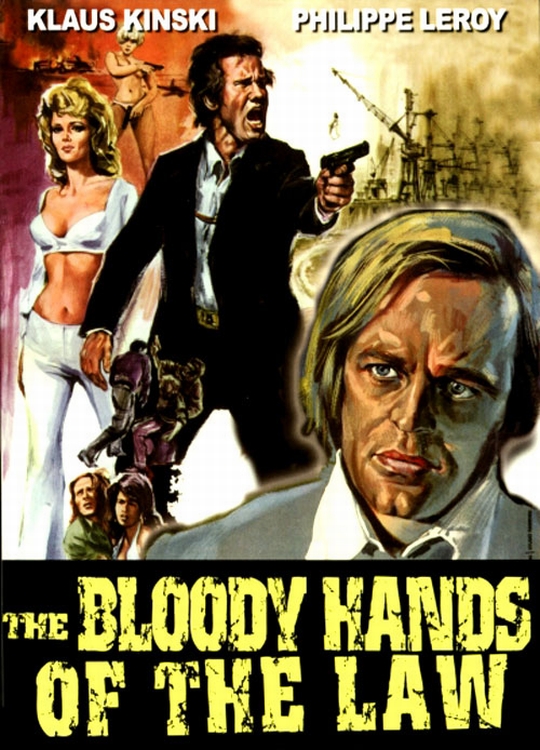

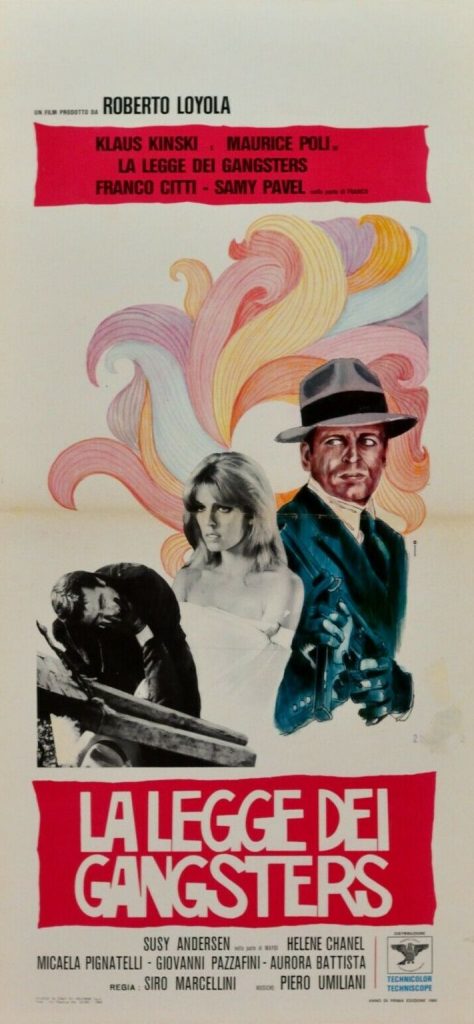

Dir: Siro Marcellini

Star: Maurice Poli, Franco Citti, Klaus Kinski, Hélène Chanel

a.k.a. Gangsters’ Law

There’s more than a hit of Reservoir Dogs here – or, perhaps that should be Serbatoio Cani? We begin with a shoot-out in the streets of the Italian city of Genoa, where bank robbers are being pursued by the cops as they attempt to getaway with their 50 million lira haul. Reinforcements on the side of the thieves turn up, allowing them to make their getaway. But only at cost, one of them having been badly wounded in the exchange. As they head away, we flash back to seeing what took the gang to that point, and also forward to see how things unfold. Which may, or may not, involve one of them being an informer for the cops.

We start with Bruno Esposito (Citti), a kid from the country who has come up to live and work in the city. When he gets involved in a brawl at a disco, the resulting fall-out gets him fired from his job in a body-shop, and begins his drift into the world of crime. A car theft turns into a house burglary, which brings this angry young man into the sphere of crime boss Rino (Poli), who sees something of himself in Bruno. Also recruited is a young hanger-on to the upper classes, because Rino finds out he had set that up in order to swipe some jewels from his girlfriend, Contessa Elena Villani, and pay off a gambling debt. He spends his time at hippie discos, saying things like, “We don’t dig girls who are uptight and with bourgeois morality.”

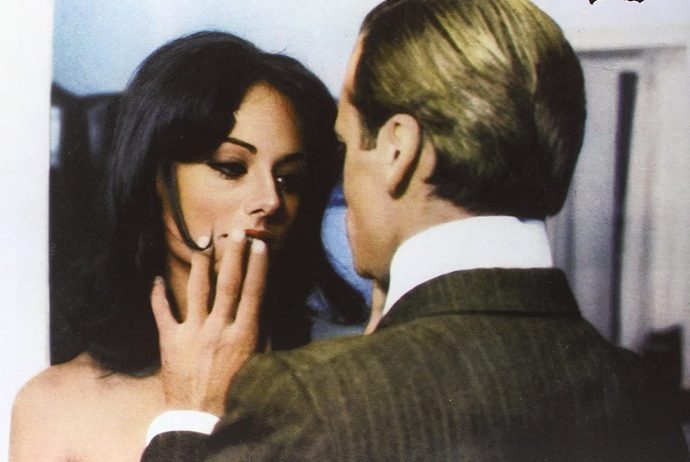

Kinski’s character, Regnier, and his ever-present hat (more on which later), are introduced just after the half-hour point, casually buying his girlfriend an expensive ring, He turn out to be the financier for the operation, and drives a hard bargain when negotiating with Rino. Regnier demands 50% of the take, even though, as Rino points out, it’s the gang who will be taking most of the risks. We also get to see his romantic technique with his moll, which is best described as imitating a leopard eating off someone’s face. I guess when you are being bought some really expensive jewellery, you have to put up with that kind of animalistic pawing. In the role of his girlfriend, Donatella Turri does quite a good job of pretending to enjoy it though.

The robbery plan is to take the white van belonging to the bank messenger out of commission, and then send a stand-in – hopefully one which is convincing enough to pass muster – in his place to collect the cash. This works, but the sudden arrival of the police on the scene precipitates the shoot-out with which we opened. They only escape by the skin of their teeth, taking their casualty with them. When everyone meets up after the event, the financier shoots the injured man dead, to the disgust of Rino – presumably for fear of an unwanted loose end. However, this causes Rino to rip up the original deal, telling Regnier he’s lucky to be getting to walk away with the life. Needless to say the industrialist feels otherwise.

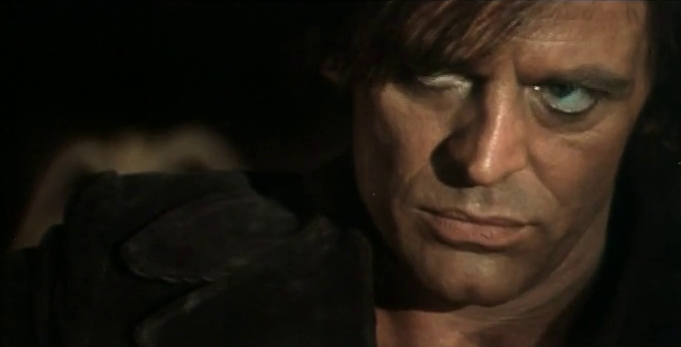

He celebrates the success of the endeavor, by hooking up with his girlfriend for another session of intense face-nibbling. At least Regnier does her the courtesy of taking off his hat first. Though he then shoots her, before reclaiming the ring. I guess her face can’t have tasted all that good. The rest of the gang have split up, and are hiding out, while they wait for the heat to die down. With the police having blocked the roads out of town, they’re forced to stay in Genoa – which makes it considerably easier for Regnier to find them. One is killed by the side of the road; another in a hall of mirrors. Rino is quickly figuring out what’s up, but it’s Bruno who gets to go toe-to-toe against Regnier, in an extended battle down by the water.

The most remarkable feature of which, is probably the way that Regnier’s hat remains attached to his head through 90% of the brawl. That’s fair enough when he is stalking his prey. But even when they are rolling around on the ground or flailing boat-hooks at each other, the hat stays on. It’s not until they begin splashing about in the shallows, that it finally parts company (and I was sad to see it go), shortly before Bruno gains the upper hand and drowns his one-time accomplice. Not that it helps him much, as the police arrive, in hot pursuit, and take him into custody. Rino tries to make it out of the country by boat, but the authorities get tipped off and are waiting. He goes all James Cagney and refuses to let them take him alive.

It’s all rather fragmented, and there seems to be a lot of things which happens without explanation. Why does Regnier get so bent out of shape about the robbery causing a shoot-out? How do the police know where to be? Shouldn’t somebody at the bank notice that the messenger, whom they clearly know well, isn’t the messenger? Why didn’t the gang hold onto the van they diverted, and prevent the alarm from being raised? All of these are poorly explained, and the bouncing around between the multiple characters isn’t managed particularly well either.

I did like the score by Piero Umiliani, a composer about whom I spoke a bit, in my review of Death’s Dealer. It manages to cover quite a lot of bases, in terms of both styles and emotions, yet does so effectively. Otherwise, though, there’s not much to recommend this. Outside of Kinski’s presence – playing another weird character – it’s not one I’d say was worth bothering with, unless you’re a hardcore completist for Eurocrime flicks