Dir: Serge Moati

Star: Klaus Kinski, Bernard Blier, Marie Dubois, Jean-Luc Bideau

a.k.a. Nuit d’or

Two years after supposedly being disposed of, in circumstances which are, at least initially, very murky, Michel Fournier (Kinski) comes back from the grave. And, as you can imagine, he’s not happy. Fournier announces his return with notes and creepy dolls, sent to those responsible for his alleged “death.” They include his brother, Henri (Bideau), and police commissioner Pidoux (Blier), who got Fournier accused of being the “golden chain killer,” for (again, supposedly) murdering a little girl. Muddying the water further is Michel’s previous relationship with Henri’s wife Veronique (Dubois), which led to a daughter, Katherine.

Michel abducts the young girl, and uses her as leverage – though quite what his endgame is with this kidnapping, remains rather opaque. It may be an attempt to rekindle the flame with Veronique, though child kidnapping seems a bit of a poorly conceived option. Indeed, the same could be said for quite a few other elements, such as the “Nuit d’Or” casino which gives the film its title, and where it both opens and closes. While there are suggestions that Michel was a heavy gambler, it’s never clear how this quite fits into the overall scenario.

Michel abducts the young girl, and uses her as leverage – though quite what his endgame is with this kidnapping, remains rather opaque. It may be an attempt to rekindle the flame with Veronique, though child kidnapping seems a bit of a poorly conceived option. Indeed, the same could be said for quite a few other elements, such as the “Nuit d’Or” casino which gives the film its title, and where it both opens and closes. While there are suggestions that Michel was a heavy gambler, it’s never clear how this quite fits into the overall scenario.

Similarly, there’s the weird, almost apocalyptic, religious cult to which he has ties: The Temple of the Son of the True Light. They hold their services in a car-park decked out with drapes, quote heavily from the Book of Revelations and their leader appears to be a midget in a coffin. Michel ends up using fellow disciple Sister Andrée (Anny Duperey) to watch over Katherine, though her stricter approach to their captive triggers its own problems. It’s perhaps significant that Michel ends up being too damn weird for the cult, who turn him in to the cops, via a disembodied voice. Imagine, if you will, Jim Jones throwing his hands up and saying, “Who the hell is this weirdo? I don’t want anything to do with him!”

The scenes with Michel opposite Katherine certainly possess disturbing elements, as shown in the still on the right. Some of this is hindsight, in the light of subsequent accusations by Klaus’s real daughter, Pola. But it’s also unsettling in the context of the movie, with the allegations regarding Michel as a killer – apparently high-profile enough, he’s recognized by a woman in the street while waiting for his daughter. But like the other elements mentioned above, these just don’t gel into anything approaching a coherent whole. This could be a decent policier, following Pidoux’s efforts to solve the kidnapping. Or been told from the point of view of Henri and Veronique, as their marriage unravels under the pressure of events. Or been a roaring rampage of revenge for Michel, getting his own back on those who wronged him. It nods towards each angle, yet is unsatisfactory as any of them, perhaps not helped by a 78-minute running time that restricts much development.

Director Moati has spent most of his career in TV movies and/or documentaries, and I do suspect this is the kind of material which would need a far stronger hand to control it. Some places have compared it to an Italian giallo, and while I can see where this is coming from, it doesn’t quite have the atmosphere, combining horrific elements with eroticism, which I’d generally expect. That said, there is one scene which anyone who has watched this will remember: the puppet show Michel puts on for Kathleen, to explain the situation to the child. This includes marionettes in the form of all the major players, including one of Michel/Kinski (shown, top) which is both disturbingly creepy and lifelike. Or perhaps, because it’s lifelike. The scene in question is below: since it’s unsubtitled in the clip, here is the narration Michel provides.

“Once upon a time, there was a man called Michel. He was alone. All by himself. No one loved him. His father, Charles, was always finding what he did was wrong. His brother, Henri, was jealous because Michel had met before him a very beautiful queen. Véronique. Queen Véronique loved Michel very much. So… Charles and Henri wanted to make Michel disappear. But Michel was not dead. He was in Africa. There, all alone, he was thinking about Queen Véronique and the little princess Catherine. You. He loves them so much. He says to the queen, “Come.” He says to the princess, “Come.” All three go away. And they are happy together. Sleep, Catherine. Sleep…”

There’s a decent supporting cast, also including Maurice Ronet as the owner/operator of the casino. Blier would go on to work with Kinski again, making his penultimate movie appearance in Kinski’s Paganini.. Michel’s mother is played by the venerable German actress, Elisabeth Flickenschildt, in her final role, who had worked with Klaus on a couple of the Edgar Wallace films during the sixties, including The Indian Scarf. One oddity: though speaking his own dialogue in French, when shown in his home country, Kinski’s voice was dubbed back into German, by Hans-Michael Rehberg.

The movie has the germs of some interesting ideas, and isn’t short on style, either. It’s nice to see Klaus firmly front and center, and his performance works, because Kinski is a well-cast choice for the character. However, the film as a whole never meshes the elements together. It feels to me the biggest problem is a script that apparently can’t decide what it considers important, and ends up leaving all its components under-developed and, thus, underwhelming. The ending doesn’t complete the film with an exclamation point, or even a full-stop, more like a set of ellipses, petering out in a way which could hardly be a greater disappointment if it tried. It remains worth a look for the acting, and for the puppet-show, though I wonder, what happened to the Kinski marionette? I’m a little surprised it didn’t go on to have its own, successful career as a cheaper (and, certainly, more amenable!) alternative to the real thing…

The focus is, instead, on Macho Callaghan (Cameron) – note the “g”, for legal reasons! – who is the sole survivor of the Carson gang, after they are attacked and massacred by Butch Cassidy (Betts) and his gang. After recovering, Callaghan teams up with another renegade, Buck O’Sullivan, to take revenge on the people responsible – a process complicated by Cassidy’s group having split in two, with Buck among the men now following Ironhead Donovan (Mitchell). Those two parties hold no love for each other either, having split after a rigged game of poker. The vast bulk of the running time sees Callaghan and O’Sullivan working to infiltrate Ironhead’s gang, and/or attack Cassidy’s. It’s all incredibly dull, even by the low standards of Fidani, whose reputation as among the worst of spaghetti Western directors is certainly not diminished by this.

The focus is, instead, on Macho Callaghan (Cameron) – note the “g”, for legal reasons! – who is the sole survivor of the Carson gang, after they are attacked and massacred by Butch Cassidy (Betts) and his gang. After recovering, Callaghan teams up with another renegade, Buck O’Sullivan, to take revenge on the people responsible – a process complicated by Cassidy’s group having split in two, with Buck among the men now following Ironhead Donovan (Mitchell). Those two parties hold no love for each other either, having split after a rigged game of poker. The vast bulk of the running time sees Callaghan and O’Sullivan working to infiltrate Ironhead’s gang, and/or attack Cassidy’s. It’s all incredibly dull, even by the low standards of Fidani, whose reputation as among the worst of spaghetti Western directors is certainly not diminished by this.

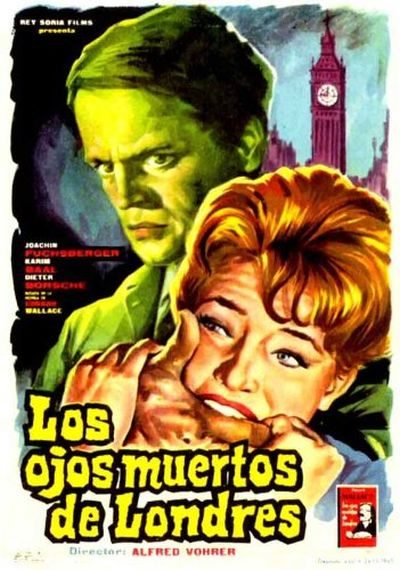

The hero is Scotland Yard’s Inspector Larry Holt (Fuchsberger), who is investigating a series of deaths by drowning in the Thames, which he’s convinced are murders, even though the forensic evidence suggest accidental demises. We know from the start that he’s onto something, having watched as Blind Jack, a hulking bald brute with cloudy eyes, attacks his chosen victim, an Australian wool merchant. A Braille note found in the victim’s pocket brings in specialist Nora Ward (Baal), who helps uncover a possible link to “The Dead Eyes of London,” an organized criminal group of blind beggars, and a mission for sightless old men run by the Reverend Paul Dearborn.

The hero is Scotland Yard’s Inspector Larry Holt (Fuchsberger), who is investigating a series of deaths by drowning in the Thames, which he’s convinced are murders, even though the forensic evidence suggest accidental demises. We know from the start that he’s onto something, having watched as Blind Jack, a hulking bald brute with cloudy eyes, attacks his chosen victim, an Australian wool merchant. A Braille note found in the victim’s pocket brings in specialist Nora Ward (Baal), who helps uncover a possible link to “The Dead Eyes of London,” an organized criminal group of blind beggars, and a mission for sightless old men run by the Reverend Paul Dearborn.

As a contrast, it came out between On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and Diamonds are Forever, much more the kind of spy films produced during this era. This is closer to Le Carre than Fleming (even if I acknowledge the gap between the 007 novels and their adaptations!), being as interested in the mechanics of the spy business as its characters. The focus for the latter shifts repeatedly, from Nicolas to Dominique to Coster (Michel Constantin), the French counter-espionage agent leading the investigation, to Helen). Two scenes in particular stand out. There’s a long, almost silent depiction of Nicolas’s break-in to his target and, later, another lengthy sequence where another of Helen’s minions, knowing he’s being followed, tries to shake the tail. This switches between him and the French authorities, who know he knows and use all their resources to keep on their target.

As a contrast, it came out between On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and Diamonds are Forever, much more the kind of spy films produced during this era. This is closer to Le Carre than Fleming (even if I acknowledge the gap between the 007 novels and their adaptations!), being as interested in the mechanics of the spy business as its characters. The focus for the latter shifts repeatedly, from Nicolas to Dominique to Coster (Michel Constantin), the French counter-espionage agent leading the investigation, to Helen). Two scenes in particular stand out. There’s a long, almost silent depiction of Nicolas’s break-in to his target and, later, another lengthy sequence where another of Helen’s minions, knowing he’s being followed, tries to shake the tail. This switches between him and the French authorities, who know he knows and use all their resources to keep on their target.

The interplay between these factions and individuals is always intriguing. Hogan in particular is a wild-card, liable to explode into sudden brutality at the drop of a card. Yet that appears to make him something of a chick-magnet. One of the hostages basically flings herself at him, resulting in this immortal exchange between her and Hogan:

The interplay between these factions and individuals is always intriguing. Hogan in particular is a wild-card, liable to explode into sudden brutality at the drop of a card. Yet that appears to make him something of a chick-magnet. One of the hostages basically flings herself at him, resulting in this immortal exchange between her and Hogan:

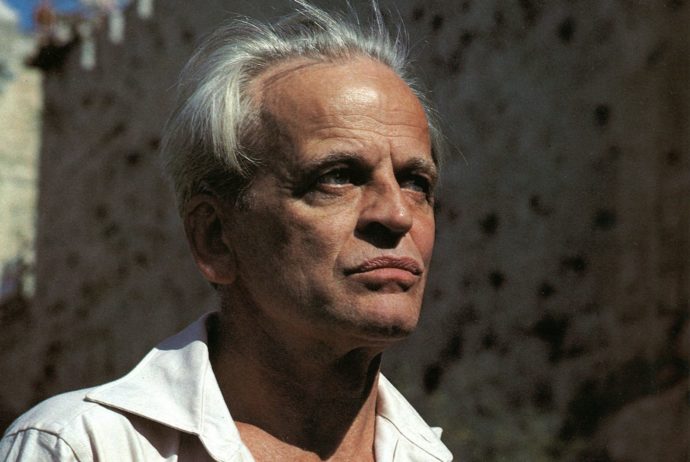

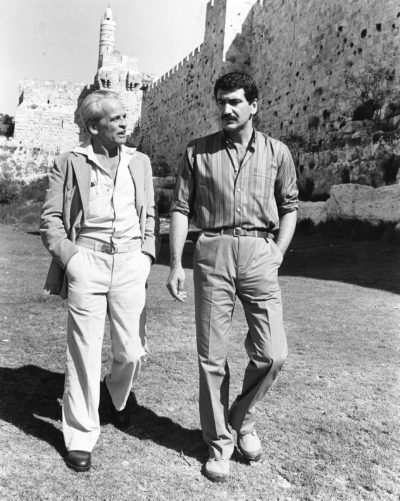

I did find it admirably even-handed. There have been plenty of other films which covered the undercover war between Mossad and their terrorist adversaries in the wake of the Munich massacre, but these have generally leaned more heavily toward the Israeli viewpoint. This is more neutral, and certainly considerably more cynical in its approach. Both sides have no qualms at all about using and deceiving people to achieve their ends, and it’s fortunate the script follows the novel to its downbeat conclusion. where Charlie is basically broken by the mission, and the realization she has been utterly played as a patsy by Kurtz and his crew.

I did find it admirably even-handed. There have been plenty of other films which covered the undercover war between Mossad and their terrorist adversaries in the wake of the Munich massacre, but these have generally leaned more heavily toward the Israeli viewpoint. This is more neutral, and certainly considerably more cynical in its approach. Both sides have no qualms at all about using and deceiving people to achieve their ends, and it’s fortunate the script follows the novel to its downbeat conclusion. where Charlie is basically broken by the mission, and the realization she has been utterly played as a patsy by Kurtz and his crew.

He goes back into the forest and meets another legend, the malicious giant Dutch Michael (above). He convinces Peter that the heart is the cause of all woes, and allowing Dutch Michael to add Peter’s to his collection – which includes Ezekiel’s – will put him back on the road to business success. Yes, the brick-like moral here is that the rich are

He goes back into the forest and meets another legend, the malicious giant Dutch Michael (above). He convinces Peter that the heart is the cause of all woes, and allowing Dutch Michael to add Peter’s to his collection – which includes Ezekiel’s – will put him back on the road to business success. Yes, the brick-like moral here is that the rich are