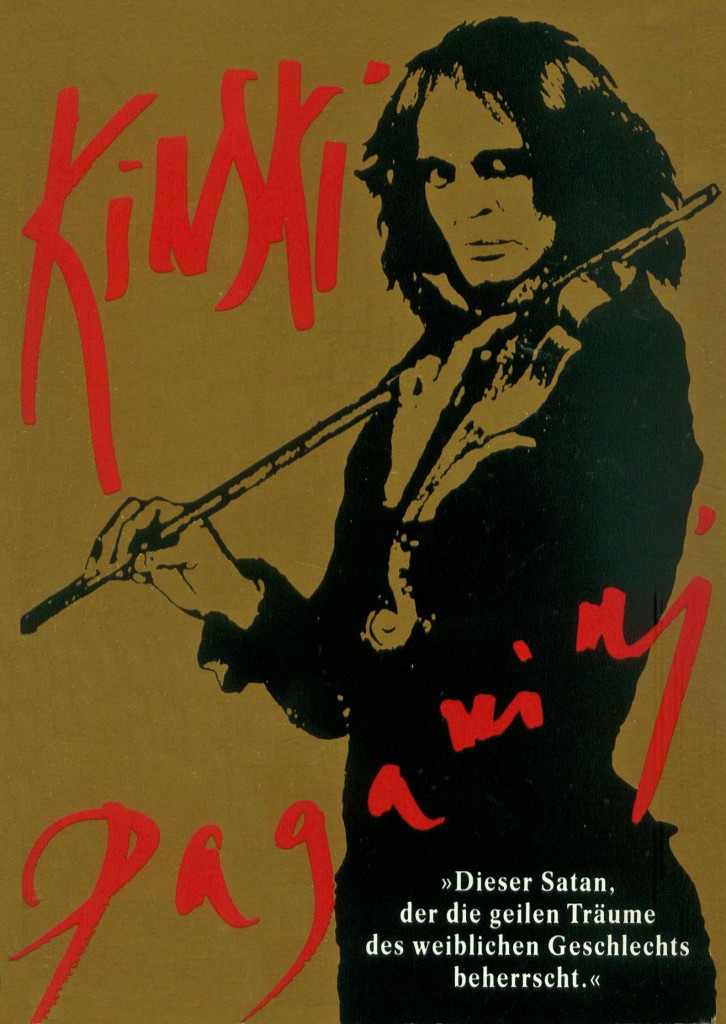

Dir: Klaus Kinski

Star: Klaus Kinski, Debora Kinski, Nicolai Kinski, Dalila Di Lazzaro

“Everyone knows what a pig he is. The whole world knows what a dissipated life he leads. It’s disgusting. His only interests in life are… money and, of course, women. The younger, the better, and if possible, underage. He’s obsessed with sex.”

The above lines are spoken at the beginning of the movie, by two priests on their way to Paganini’s house where the musician is dying, in an effort to administer last rights and save his immortal soul. But, obviously – and in the light of subsequent allegations, unfortunately – they are intended to be applied as much to Kinski himself. Klaus clearly sees himself as a spiritual descendant of Paganini, and even referred to himself as Paganini reincarnated: a great artist, whose genius is misunderstood and derided by his critics, but who is capable of touching the hearts of his audience directly. Quite how accurate he is there, could politely be called a topic for debate, but let’s face it: he had a one-man show in which he played Jesus Christ. No-one had a higher opinion of Klaus Kinski’s talents than Klaus Kinski.

However, it’s clear that whatever skills he had on the stage and in front of the camera, did not translate in any way to writing and directing. For the result is a complete mess, and an utter failure in terms of providing any significant insight into the life of Paganini. As an insight into Kinski’s self-image and psychological identity, on the other hand, there’s enough material here to keep an entire Las Vegas convention of psychiatrists happy. As disasters go, it’s a glorious, fascinating one, a misconceived project from beginning to end.

Werner Herzog says Kinski repeatedly asked him to direct the film, but Werner turned it down. When a man who dragged a full-scale boat over a mountain for his movie, calls your script “unfilmable,” it’s probably best to rethink it a bit. Klaus, naturally, had no such second thoughts, instead opting to direct it himself, and the result is the most batshit-crazy biography ever of a classical musician. And considering this field includes the likes of Ken Russell’s Lisztomania, that’s some gold standard for insanity.

It’s the kind of film which breeds urban legends, of varying credibility. There’s rumors of a 12-hour version. Or that the film contains so many long shots, because this allowed the crew to stay out of range of Kinski’s wrath. Before going on, I should mention the review is based on the director’s cut version, which runs 94 minutes. The producers, when they saw what he had delivered, were apparently appalled, calling it “pornographic”- not without reason – and suing Kinski. Their version, which received a minimal release, runs 80 minutes, although one presumes, is no more coherent.

For there is little or no effort at any kind of narrative structure here: what you get is a series of montages, approximately 50% of which involve sex (or perhaps it just seems that way), and most of those involve Kinski. But not all. In one of the film more notorious sequences, Di Lazzaro, playing noblewoman Helene von Feuerbacha, is overcome in her carriage with lust at seeing a stallion servicing a mare, and begins masturbating furious while thinking of Paganini.

This is, it appears, perfectly normal. For another early montage shows Paganini on stage, while the (young, attractive) women in the audience are virtually orgasming in their seats, and generally reacting in a way that recalls Beatlemania at its height. There’s a lot of this kind of thing, unsubtly suggesting he is entirely irresistible to women: later on, one of his conquests goes on a self-abasing demand that he make love to her again, mere seconds after he has dismounted. “He is an animal!” it is bemoaned. “Given the chance, he would rape every girl he meets. Especially the ones underage!” Again with the benefit of hindsight and future events, an unfortunate choice of sexual predilection, not apparently rooted in biographical accuracy. Though one of the film’s themes appears to be how the legend of Paganini was exaggerated to malign him by his enemies, which could conceivably apply equally as much to Kinski and his legacy. Here, Paganini certainly doesn’t need to rape anyone, his partners are all entirely and enthusiastically willing.

This is, it appears, perfectly normal. For another early montage shows Paganini on stage, while the (young, attractive) women in the audience are virtually orgasming in their seats, and generally reacting in a way that recalls Beatlemania at its height. There’s a lot of this kind of thing, unsubtly suggesting he is entirely irresistible to women: later on, one of his conquests goes on a self-abasing demand that he make love to her again, mere seconds after he has dismounted. “He is an animal!” it is bemoaned. “Given the chance, he would rape every girl he meets. Especially the ones underage!” Again with the benefit of hindsight and future events, an unfortunate choice of sexual predilection, not apparently rooted in biographical accuracy. Though one of the film’s themes appears to be how the legend of Paganini was exaggerated to malign him by his enemies, which could conceivably apply equally as much to Kinski and his legacy. Here, Paganini certainly doesn’t need to rape anyone, his partners are all entirely and enthusiastically willing.

In between the sex, you get footage of Paganini stalking the streets of Venice in slow-motion, violence to both a chicken and a goat, and scenes of family life, with his wife Antonia Bianchi, played by Debora Caprioglio. The two were having a relationship, even though Caprioglio was one-third Kinski’s age, and credited as Debora Kinski even though she was never actually married to Klaus [curiously, she also played the wife of his character in their other film together, Grandi cacciatori] Extending the familial feel, Nastassja was supposed to have been involved, but it’s reported, “after three days she fled from the set in tears, never to return”.

Instead, we do have Klaus’s son Nikolai, by his third wife, Minhoi. It’s actually kinda touching, because the affection between father and son appears entirely genuine on both sides. This also leads into the film’s best sequence, with Paganini playing the violin with increasingly berserk passion, as his son watches, entranced and holding a kitten. Which is a good place to laud Salvatore Accardo, whose performances provide the music for the film, and is awesome. If nothing else, he was apparently satisfied with Kinski in the role, saying, “Paganini has finally come back to us through you, Klaus.”

Mind you, that comes from the film’s website which says, almost proudly, “Just as Paganini didn’t need to tune his violin because he could play his unique music anyway, so Kinski doesn’t need to prepare, repeat or rehearse the scenes – he just does it. Also as the director, he doesn’t rehearse or repeat – he just shoots.” If having the ring of plausibility, this is probably the movie’s biggest problem: it’s no coincidence that the quality of Kinski’s performances appear almost directly related to the degree any given director was prepared to butt heads with him, e.g. Herzog. Here, there wasn’t apparently anyone with the courage to stand up to Kinski and rein in more self-indulgent ideas, such as apparently insisting on everything being shot with natural light [though this may partly be an issue with the transfer of the director’s cut].

This was described by one viewer as “very possibly the worst film I’

Stefano Loparco has written a book about the making of this movie titled “Klaus Kinski – Del Paganini e dei capricci”. He interviewed the producer, Augusto Caminito, who confirmed that he intended to cast Nastassja in the role of Antonia Bianchi and that she was willing to accept the part.

“Nastassja should have been Antonia in Paganini, a role later played by Debora Caprioglio who in any case did very well. But Nastassja was Nastassja…”

“When I offered her the part of Antonia – it was the third or fourth day of shooting – only a few sequences had been recorded. Nastassja subordinated her decision to viewing the filmed footage. In the following days we set up an appointment in Rome to show her the material and, to my great satisfaction, she not only liked it but said she was willing to accept the part. I was thrilled! Having Klaus and Nastassja in the same film would have aroused the curiosity of the audience and given the film international standing. Yet things turned out differently.”

“At the end of the meeting, I proposed to Nastassja that I take her back to the hotel. I wanted to avoid her being left alone with her father. Theirs was a visceral relationship, difficult to understand. That relationship made of silences, gazes, long faces and tenderness seemed ambiguous to me and, in any case, cumbersome. So when Klaus told me he was going to take his daughter, I insisted. But he was the one who prevailed. I wasn’t wrong. The next morning Klaus showed up in my office saying that the part of Antonia was Debora’s. So he had decided. I asked him about his daughter but he didn’t answer. That was the last time I saw Nastassja.”

Costume designer Bernadette de Cayeux gives an agreeable account of Kinski, at least initially…

“At the time I was young and without much experience. It was Alfieri who wanted me but, obviously, the last word belonged to Kinski and so we met him that day at the Hilton in Rome. I remember that after introducing myself with my first and last name – Bernadette de Cayeux – he immediately addressed me: ‘De Cayeux? Like Colin de Cayeux, François Villon’s fellow venturer?’; ‘Yes’ – I replied. And he: ‘Incredible! What a coincidence! Many years ago, in Paris, I recited Villon’s poems and in one the name of Colin de Cayeux is mentioned… it’s more than a coincidence: it’s destiny!’ – he said. Then, looking at Alfieri, he added: ‘Yes, I want her!’. And so I joined the cast of Paganini.”

“I met Kinski at least twice, even at his home on the Appian Way, and I must say he was always very kind, a true gentleman with a refined education. When Nastassja came to visit him at his villa, he even introduced me as a godsend. In the tailoring – during the rehearsals – he was kind to everyone. He was always in a hurry. He was also very fussy and I understood it very well since I was too. He didn’t overlook any detail: the color of a ribbon, the height of the hat and other details and I think he never spoke out of turn.”

“Of course, some of his behavior had upset me. For example, if someone inadvertently got in his way on the street, he would yell at them like a madman trying to catch them. But anyway, initially I found myself very happy and I especially appreciated Kinski’s professionalism. Then he started the preparation of the film and… I thank God I survived it!”

Once filming began Bernadette would experience a more unsympathetic and infamous side of Kinski.

“From the first day of shooting, Kinski was on edge. Of the well-mannered and attentive man I had met during the preparation of the film, there was no trace. He yelled, gesticulated like a madman and every slightest delay was repaid with shouts and intimidation. He had become Paganini, a monster. The atmosphere on set was very tense. Fear dominated. We all trembled when he barged into the tailor shop! He went so far as to rip off his shirt and throw it in my face…”

“Then one day the worst happened. We were working on a sequence where little girls dance outside on the lawns. Barely ten-year-old girls were planned for that scene but at the last moment a group of already trained teenagers arrived and it was necessary to adapt the clothes. Of course, anything can be done, but the work took some time. Impatient with the wait, Klaus burst into the tailor shop: ‘What the fuck are you doing? What the fuck are you doing?” He said walking towards me menacingly. I was squatting tying a little girl’s shoes. I didn’t have time to answer him before he pushed me making me fall to the ground. I laid motionless, humiliated, frightened. I didn’t want to get up again. I started to cry. And as I cried Kinski laughed and said, ‘Look at Bernadette crying!” Look how she cries!'”

“When I returned home that evening, the decision had already been made: no one had ever laid hands on me and I would never let anyone again. The next day I communicated my decision to abandon the project. I never returned to the set. In the following days, on several occasions, Alfieri called me telling me that Kinski was sorry for what had happened, and was asking me to return to the set. He also tried to minimize what happened: ‘But you know how Klaus is… come on, go back to work… don’t be silly…’. I didn’t. Titus Vossberg took my place. I offered him to sign the film with his name but he didn’t accept and, after all, I’m grateful to him.”

I forgot to include the source!

https://stefanoloparco.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/del-paganini-e-dei-capricci.pdf

https://stefanoloparco.com/2016/02/18/lipotesi-nastassja/