Dir: Maurizio Pradeaux

Star: Richard Harrison, Pilar Velázquez, Giacomo Rossi-Stuart, Klaus Kinski

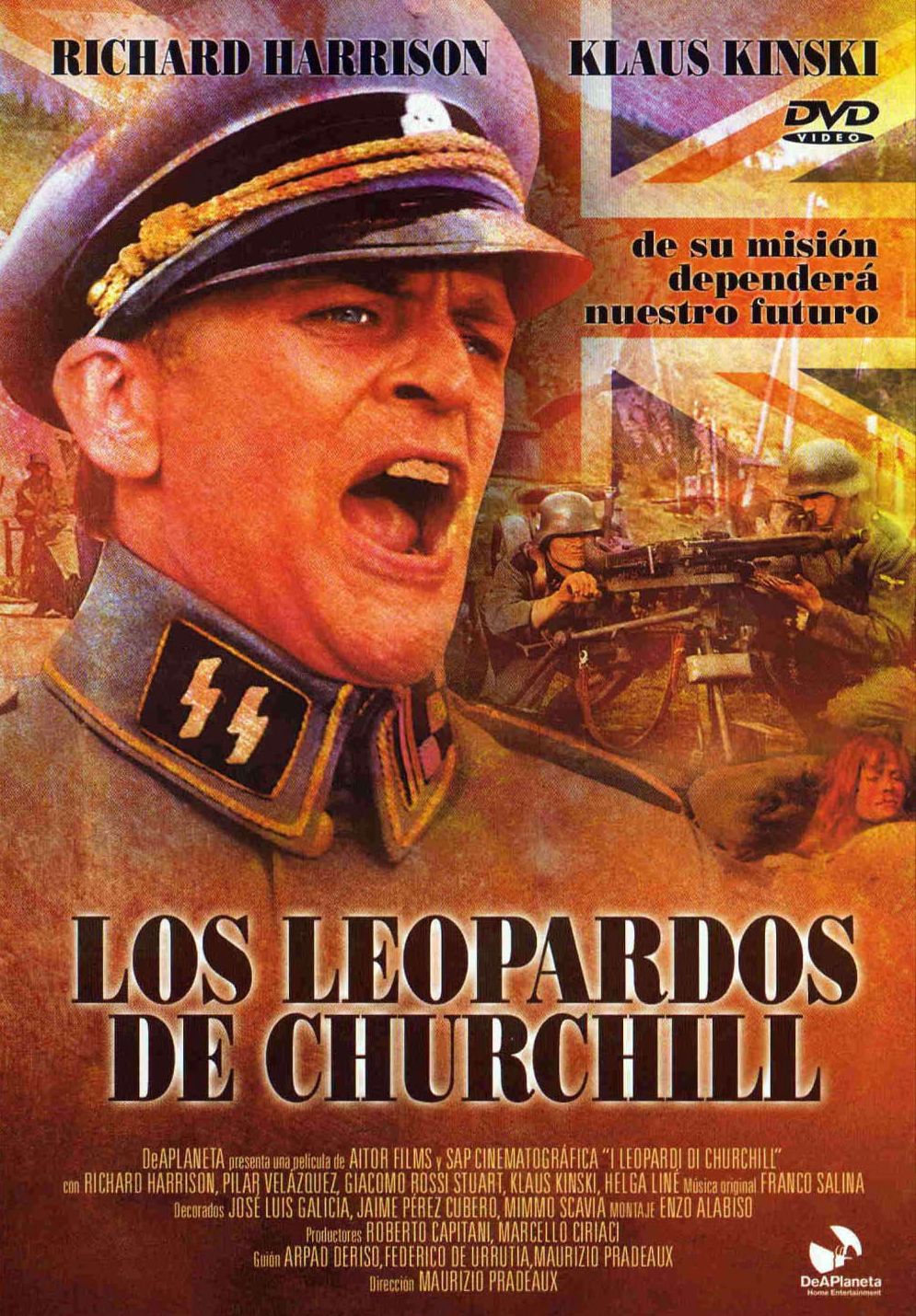

Can’t complain about the poster, though the truth is that Kinski’s role, while pivotal, is more supporting than as front and center as it would have you believe. The true star is Harrison, who plays twin brothers, both lieutenants in the armed forces – only one is a Nazi, Lt. Hans Müller, the other a Brit, Lt. Richard Benson. The former is in charge of the defenses for a French dam, and with D-Day imminent, Winston Churchill comes up with a plan to blow up the dam, which would cause havoc to the German supply lines. The plan involves taking out Muller, and plugging in Benson, who will then be ideally placed to assist a group of commandos, led by Major Powell (Rossi-Stuart) parachuted into enemy territory with the tools necessary to destroy the facility, with the additional help of the local resistance, one of whose members (Velázquez) falls for Benson. Kinski plays the local SS commander, Captain Holtz, who grows increasingly suspicious that pseudo-Müller’s behavior is inconsistent with the real thing, and brings an old flame back from Paris to confirm these doubts.

Can’t complain about the poster, though the truth is that Kinski’s role, while pivotal, is more supporting than as front and center as it would have you believe. The true star is Harrison, who plays twin brothers, both lieutenants in the armed forces – only one is a Nazi, Lt. Hans Müller, the other a Brit, Lt. Richard Benson. The former is in charge of the defenses for a French dam, and with D-Day imminent, Winston Churchill comes up with a plan to blow up the dam, which would cause havoc to the German supply lines. The plan involves taking out Muller, and plugging in Benson, who will then be ideally placed to assist a group of commandos, led by Major Powell (Rossi-Stuart) parachuted into enemy territory with the tools necessary to destroy the facility, with the additional help of the local resistance, one of whose members (Velázquez) falls for Benson. Kinski plays the local SS commander, Captain Holtz, who grows increasingly suspicious that pseudo-Müller’s behavior is inconsistent with the real thing, and brings an old flame back from Paris to confirm these doubts.

The antecedents in this case are classic war flicks such as The Guns of Navarone (1961), The Heroes of Telemark (1965), and Where Eagles Dare (1968), depicting similar missions in which a small group of Allied soldiers are dropped behind Nazi lines, with the aim of taking out a key piece of local infrastructure. Obviously, this has nowhere near the same degree of star power, nor can it manage the same degree of spectacle. The latter is particularly obvious when – and I trust this isn’t much of a spoiler – the dam is blown up at the end, which is depicted in a mix of stock footage and painfully bad model work, that bears only the faintest resemblance to the landscape shown as its actual location. There’s more stock footage book-ending the film for its credits, though at least this does provide some appropriate scene-setting for what follows.

The rest of the story is largely a collection of well-worn war clichés, as the heroic Tommies (ironically, there’s not an actual Brit to be seen – you can hear a few, apparently doing the dubbing) escape discovery by the nasty Nazis, through a combination of luck, pluck and the timely intervention of pseudo-Müller. This all builds to the actual attack on the dam, after a delay caused by the discovery that they now need a quarter-mile of waterproof cable to reach the spot underwater where they’ll place their explosives. It’s never explained why they don’t blow things up from the dry side of the edifice, but presumably there were sound, structural engineering reasons for this, that the movie just chose not to share with the audience. Their preparations are interrupted when Holtz gets the proof he needs, and realizes what’s about to happen, leading to a massive gun-battle, with so much indiscriminate automatic gunfire, it felt like something I’d have re-enacted enthusiastically in my school playground, as a nine-year-old.

Kinski’s character is, to some extent, a reprise of his role the previous year in Five For Hell. However, it’s actually among the more interesting aspects of the film, because he does succeed in being more than the typical, jackbooted stereotype. The first time we meet him, he seems positively cheerful, and is clearly a smart slice of Schwartzwalder kirschtorte, to the extent that his leading the charge into battle, literally firing the opening shots against the Allied forces, seems out of character and foolhardy. However, make no mistake: he’s an SS officer. There’s no room to question that, after two German soldiers are killed, having come too close to discovering the undercover group. He takes 20 locals – including the love interest – hostage, and lets it be known that he’ll execute them if those responsible for the deaths don’t come forward and admit it. This leads to the film’s tensest and best scene, where the hostages are lined up on the edge of a ravine, gazing down the barrel of a machine-gun. What will the anti-Nazis do? And even if they do come forward, will Holtz honor his side of the demand?

Kinski’s character is, to some extent, a reprise of his role the previous year in Five For Hell. However, it’s actually among the more interesting aspects of the film, because he does succeed in being more than the typical, jackbooted stereotype. The first time we meet him, he seems positively cheerful, and is clearly a smart slice of Schwartzwalder kirschtorte, to the extent that his leading the charge into battle, literally firing the opening shots against the Allied forces, seems out of character and foolhardy. However, make no mistake: he’s an SS officer. There’s no room to question that, after two German soldiers are killed, having come too close to discovering the undercover group. He takes 20 locals – including the love interest – hostage, and lets it be known that he’ll execute them if those responsible for the deaths don’t come forward and admit it. This leads to the film’s tensest and best scene, where the hostages are lined up on the edge of a ravine, gazing down the barrel of a machine-gun. What will the anti-Nazis do? And even if they do come forward, will Holtz honor his side of the demand?

If only the rest of the film could have tried to generate the same level of enthusiasm. The problem here is that, while the spaghetti Westerns often succeeded in bringing something new to the genre, this spaghetti War film seems content to follow slavishly in the well-trodden path of other, better movies. As a result, it’s neither fresh, nor interesting, and outside of Kinski, you’d be much better off watching the Hollywood examples mentioned above, which are superior in just about every way.