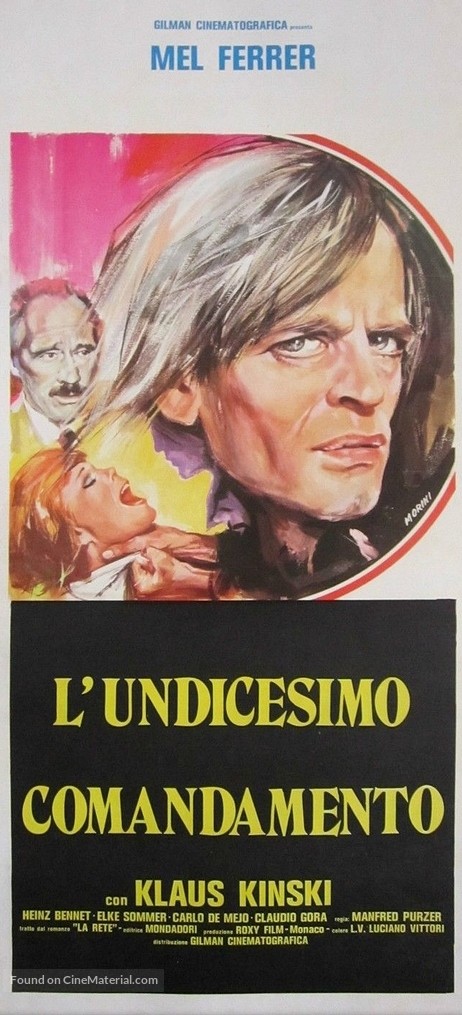

Dir: Manfred Purzer

Star: Mel Ferrer, Klaus Kinski, Carlo de Mejo, Susanne Uhlen

a,k,a, The Net

This is about what you would expect from a German take on the quintessentially Italian genre, the giallo. It’s far too stodgy to be effective, and manages to miss the point in a number of ways. While not short on the exploitative element of female nudity, it manages to carry out all examples of the other key component, violence, off-screen. While multiple murders take place, we never see them. The same year this was made, the master of the field, Dario Argento,, released Deep Red. The contrast between its insanity and the plodding, almost procedural, nature of this could hardly be greater. Indeed, except for the fact we know who the killer is all along, this perhaps has more in common with the Edgar Wallace movies of the previous decade.

The focus is Aurelio Morelli, a writer in the twilight of his career, who is increasingly disgruntled with modern life, modern people and in particular, modern women – not least a result of the contemporary disdain for and disinterest in his work. On his birthday, he strangles a prostitute with a phone-cord, a crime which leaves the police under Inspector Canonica (Heinz Bennent) baffled. However, sleazy tabloid journalist Emilio Bossi (Kinski) has figured out Morelli’s connection to the case, and blackmails the author into writing his memoirs for Bossi’s publication, including details of the murder. In exchange, Morelli will get enough money to fund a new life in another country, which does not have an extradition treaty with Italy. Bossi, meanwhile, will get a nice, lurid scoop.

The execution turns out to be not that easy. Canonica brings the hear on Bossi, suspecting he knows more about the murder than he has told the authorities. The magazine publisher insists on his son, Francesco Vanetti (de Mejo), working with Bossi as photographer on the story, even though Francesco has an almost complete loathing for the magazine. Morelli, meanwhile, is writing the promised content, but what he delivers to the journalist includes descriptions of previous murders, suggesting that the call-girl was not the first victim of his wrath. However, the author meets and befriends Agnese (Uhlen), a young woman who both respects and admires Morelli’s work. Will that be enough to stop his apparently long, ongoing string of murders before his confessions are published?

There are a bunch of issues here, not the least being the almost creepy relationships between Morelli and a slew of young women. When this was released in 1975, Ferrer turned 58, and was approaching four decades older than Uhlen, for example, who was born in 1955. Of course, it was the seventies, where standards about such things were considerably laxer, but it’s certainly an element that has not aged well. An even bigger problem is that the story just isn’t particularly interesting. As noted, there’s no question about the “who” in this dunnit, which only really leaves the “why”. Outside of a couple of rants against modern society, one in particular suggesting Morelli is on a campaign to clean up society.(a year before Taxi Driver did a lot more with that idea), we never get any real insight into what triggers his psychotic outbursts.

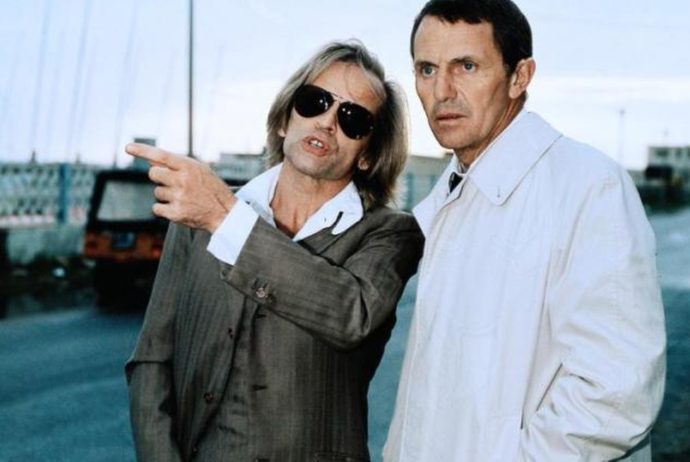

The story tries to spread itself too thinly, and never succeeds in developing any of its characters to an adequate degree. They could have focused on the murderous writer. Or the publisher’s scion, torn between his family heritage and a strong distaste for the way in which their fortune was made. Or – and this would have been my preference, for obvious reasons – on Bossi, and the way he is prepared to make almost any moral compromise, in his quest to increase the magazine’s circulation. The journalist is probably the most interesting character in the film, even prepared to let a lunatic roam free, putting potential future victims at risk, for the sake of his story. Certainly, Kinski has the best hair of anyone here, his long, flowing blonde locks at or near peak Klaus coiffure.

It is the kind of role, best described as a driven sleazebag, for which Kinski was born, and at which he was consistently good. Unfortunately, the director doesn’t seem particularly interested in exploring his character, preferring instead to follow Morelli’s angst-ridden meanderings, up and down the Italian coast. Speaking of which, outside of some gratuitous Roman ruins at the beginning, there’s not much sense of location, and they might as well have stayed in Germany. Though I was amused to discover that Italian hippie chicks apparently have a fondness for keeping their fur coats in the refrigerator. Hey, it was the seventies, who am I to judge? This is definitely one of the more obscure films in which Klaus appeared during the decade and, to be honest, it being largely forgotten seems for reason. Perhaps in other hands than Purzer’s, it might have been memorable, or at least, less bland.

Elke Sommer has a relatively small role, playing another call-girl, who was a neighor of the initial victim, and whose relationship with Bossi kicks matters off. She’s not particularly relevant to the plot beyond that, but does appear to have some not particularly nice memories of her experience working with Klaus.

In my opinion, Kinski was a nutcase, seriously. We had a scene together in the movie where he had to pull me up by my hair. That’s relatively easy to achieve… But he yanked me up so roughly, that he was tearing out tufts of my hair… I said to him, “If you dare try that again, I will beat you up!” The director joined us too and said to him, “Mind what you’re doing.” After that, he became very angry.” We were shooting at a private house which was nicely furnished, and they had a really beautiful collection of ceramic plates on a rack. He took one of his shoes and smashed them to pieces. So, you can imagine I don’t remember my dear colleague very fondly!

Elke Sommer