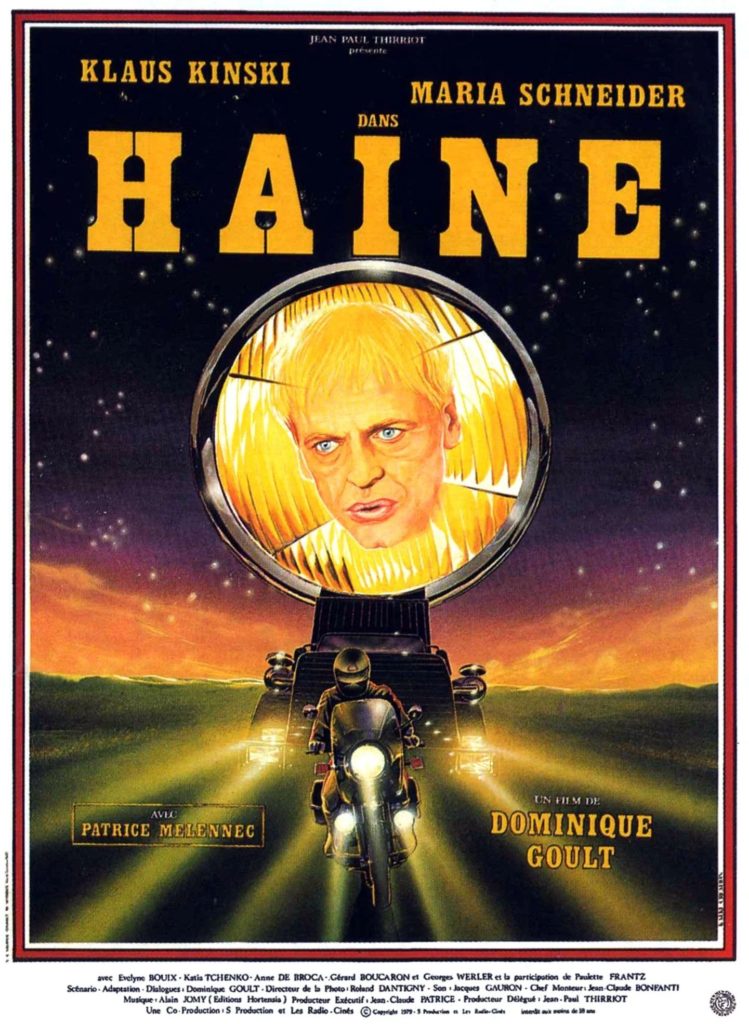

Dir: Dominique Goult

Star: Klaus Kinski, Maria Schneider, Patrice Melennec, Evelyne Bouix

a.k.a. Death Truck, Hate

Apparently, Klaus was signed to shoot a certain number of days here. When those were up, rather than negotiating an extension, he had apparently had enough, and simply left the set. Director Goult brought in a stand-in, and filmed any remaining scenes with the character wearing a motorcycle helmet. You can probably tell that certain scenes, where the wearing of a helmet would be… somewhat unusual, are likely ones involving the double. But I can’t particularly blame Klaus for his departure. The first hour of this is largely a dull and jumbled mess. Only at the end does it get the energy needed, which should have been present all along, if the plot was going to work.

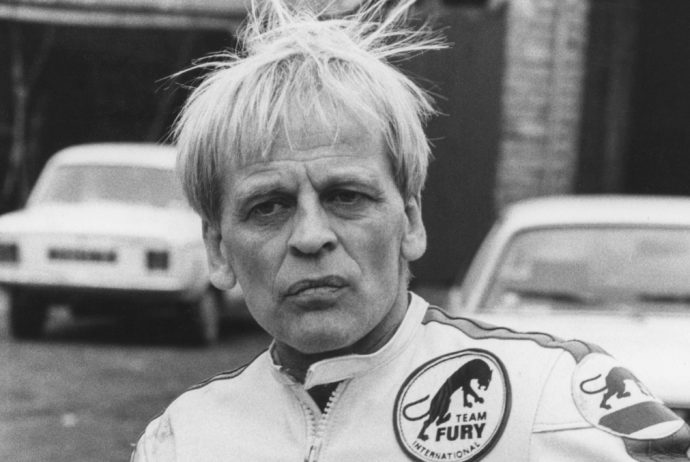

Not, in any way, to be confused with Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 urban social work, La Haine, this is very much a rural movie. Though, I suppose, it does share with La Haine the element of what happens when a community rejects those it perceives as outsiders. Yeah, I’m stretching here. In this case, it’s a small village in the country, which has been having a few issues of late with biker gangs in the area. It appears nothing apparently too bad, just the usual yobbishness and noise. However, things come to a head when a young girl in the town is killed by a unknown motorcyclist. This event coincides with the appearance of an unnamed motorcyclist (Kinski) – actually, almost everyone here is unnamed – who rides into town wearing his white leathers, immediately drawing suspicion in the girl’s death.

There seem to be two opposing forces at work: some residents want him out of town as soon as possible, while others seek to prevent him from leaving, so he can answer for his supposed crimes. While he’s in town, he strikes up a relationship with the local outcast, who does have a name: Madeleine (Schneider). She’s universally regarded as the town bike – everyone gets a ride – whose out-of-wedlock promiscuity and subsequent child has made her a pariah. But the almost trivial kindness shown by the motorcyclist strikes a chord with her. Things escalate considerably at the funeral for the accident victim, or more specifically, the “after party” held at a local bar. The biker gets into it with a local truck driver (Mellenec), after he insults Madeleine, and the brawl disrupts the supposedly solemn occasion.

From then on, the gloves are off, with the driver and his pals setting up a blockade around the town, preventing the motorcyclist from departing. And the first alternative title above does eventually make sense. While not exactly Duel, there is an extended scene where the truck pursues Kinski’s character through the countryside, both on- and off-road. This ends with the bike flying into a pond, but with the help of Madeleine, he’s able to get it out, and demands it be repaired by a local mechanic, at shotgun-point. However, word seeps out, and the trucker rounds up a posse to make the alleged child-killer pay the ultimate price. Yet, as we discover in the later scenes, things might not quite be as they seemed, with the real perpetrator perhaps closer to home than is comfortable.

There are too many unanswered questions for this to be effective. How do the villagers know it was a motor-cycle which killed the child, for a start, rather than a car or a truck? You’d think they might then start by checking out any locals that own such a bike. Apparently not. There’s there the rather odd nature of the girl herself. The film opens (after the credit sequence, including a quote from the philosopher Stendhal, which translates as “I have lived enough to see that differences breed hatred”) with her walking through the village, and there’s something off about her. She pauses outside the church where the local priest is standing reading his Bible, and just stares at him before moving on. Even her parents later admit, “There are people who feared her… because of her eyes. That look.” It made me wonder how “accidental” her death was.

We do know, from the start, that Kinski’s character is completely innocent: he wears white, while the real killer is clad in black [almost like the participants in an old-school Western!]. It’s a little odd to see him as, more or less, the victim in the film, though his problems in the early going are more annoyances, such as someone stealing a part from his bike. It’s only after the face-off at the wake that there’s any real sense of threat. Up until then, there’s just been a vague, underlying sense of light menace, exacerbated by the locals’ groundless dislike of him – in part driven by his refusal to treat Madeline with the same contempt they do. This could be due to his ignorance of her back-story; to some extent, you can see their point. He’s just a visitor, passing through, and should not be getting involved in the town’s (literal!) affairs. But there’s a certain point where – again invoking the Western motif – a man’s gotta do, what a man’s gotta do. In this case, it’s when the biker’s attempts to leave town are thwarted.

This does lead to a “high noon”-style face-off in the town square. Though without giving too many spoilers, what happens thereafter would put this more in the spaghetti Western category, rather than the traditional kind. I do wonder if there wasn’t some miscasting here. Kinski would perhaps seem better suited for the role of the truck-driver than the motor-cyclist, because of the perpetual sense of threat he would have been able to bring as the antagonist. Here, he comes over as more of a reactive character, responding to the actions of the town people rather than taking control himself. The results are rather bland, and forgettable. It’s an idea with potential, yet the execution leaves a lot to be desired.