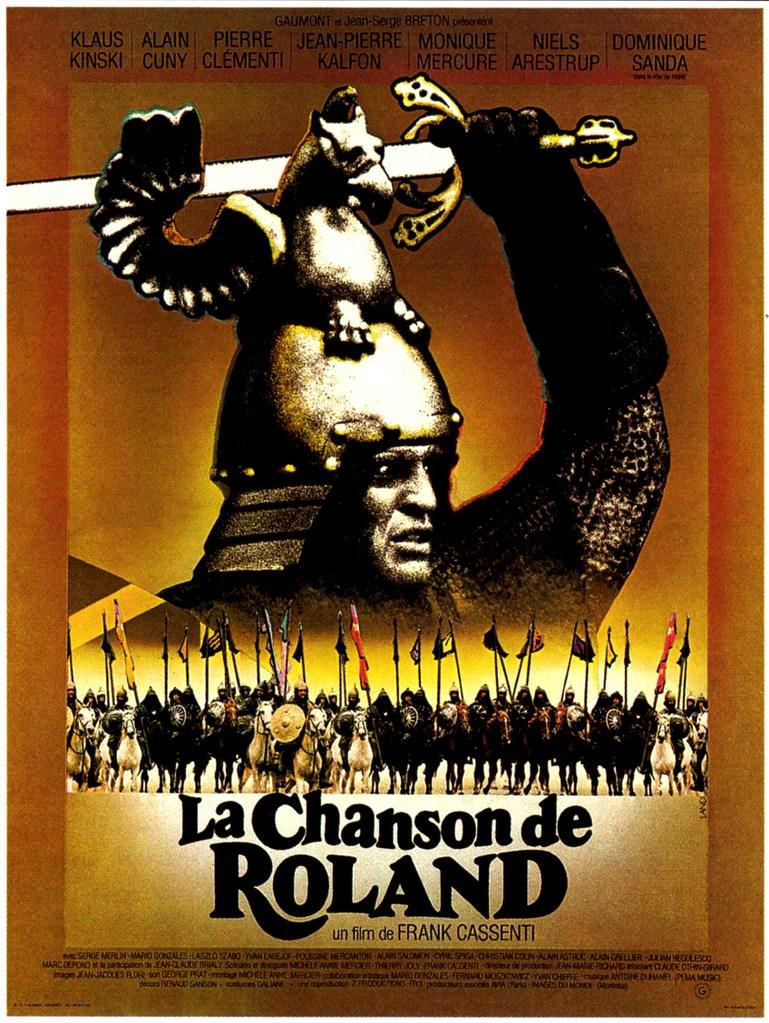

Dir: Frank Cassenti

Star: Klaus Kinski, Alain Cuny, Dominique Sanda, Pierre Clémenti

a.k.a. The Song of Roland

Kinski is not exactly the kind of person you would invite on a press tour to promote a movie in which he starred. The pattern appears to be fairly consistent, at least over the time in his career in which he was a “name” actor. Show up, do the bare minimum required by the contract, fight incessantly with the director, sexually harass any woman within reach, and bad-mouth the entire production as soon as his involvement was over. It says a lot about his performances, even in these “pieces of shit”, that Klaus still kept getting work, despite the problematic nature of his personality. Still, there are times where it’s hard to argue with him, and Roland is one such film. In a passage excised from Kinski Uncut, he described it as follows:

A miserable, painful story from the Middle Ages. The pretentious director, Cassenti, has no talent; he can win people over only with money. He is too idiotic to realize that it is they who are giving an asshole like him the chance to make a movie.

Klaus Kinski, All I Need Is Love, p.243

I’m more or less in complete agreement with him. It’s a painfully obvious and extremely preachy effort, from a director, much of whose career seems to have been based on this kind of socially conscious cinema: a French version of Ken Loach, if you will. This also tries to cram two separate stories into a film that’s ill-suited for one. Let’s begin with a quick history lesson though: what is the Song of Roland? Maybe think of it as a French equivalent to Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur. A saga, supposedly based on historical reality, but written several centuries after the fact, and intended rather more to entertain than inform. Roland was an 8th-century military leader under Emperor Charlemagne, He fought a brave rearguard defense during the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 AD, dying heroically to protect the rest of the retreating army.

The Song of Roland was an epic poem, of around 4,000 lines, written in the late 11th century, and is one of the earliest surviving works of French literature. It was a popular work for several hundred years, both in written and oral forms. It’s the latter which concerns us here. We’re now in the 13th century, and a group of pilgrims are on the Way of St. James a.k.a. El Camino de Santiago. This is a journey to the shrine of the apostle Saint James the Great, located in the North-west corner of Spain, in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. On the way, they perform the Song of Roland for the residents of the territory through which they pass, although in a variant form in which Roland is betrayed by his army allies. The film bounces back and forth between Roland’s story and that of the actors: neither has a happy ending.

More obviously, their performances help inspire a growing realization among the pilgrims about the injustices imposed on them by the strictly hierarchical nature of their society, and which are reinforced by the “official” version of Roland’s story. Many of the pilgrims are outcasts of society themselves, including whores, thieves and lepers, and they gradually become revolutionaries. Though not everyone agrees: “If these peasant revolts on the land on which God put them, then they’re made to do so by a heretical power,” goes one counter-argument. “They’re made to do it because of hunger, misery and brutality, all caused by monastical orders and lords,” is the response. This is the kind of didactic content you can expect in bulk here, right until the final line: “Violence and injustice are the masters’ weapons, but for those who rebel, even failures are victories.”

I’m sure if you were already of a fervent revolutionary Marxist bent, then you would be nodding your head in agreement at such dogmatic assertions, but it’s hard to to imagine this film changing the mind of anyone not already wholly committed to the cause. Even purely from a cinematically critical point of view, the two halves of the story never gel into a cohesive whole. Whenever one threatens to achieve clarity or momentum, bang, you’re catapulted several hundred years across time, to the same actors playing different roles, and everything collapses back to the ground. It would take a skilled director to mesh the two narratives together, and on the evidence of this, Cassenti does not have the necessary film-making chops – as Kinski eloquently put it above. His performance, both as pilgrim Klaus and the heroic Roland (below), is disinterested and forgettable.

There would probably be scope for one version or the other. Either twist the story of a historical (or, at least, semi-historical) hero to put across your intended message, or depict the awakening of a group of people in the downtrodden masses, to the realization that they are the downtrodden masses. Trying to do both seems to be have been a fatal mistake, condemning the film to be a failure as both. It’s clear where this is going to go, long before the knights descend to suppress the threat of this (very minor) rebellion – no longer the heroic figures of legends, but brutal enforcers of the current order. It’s exactly the kind of thing skewered mercilessly by Monty Python three years earlier in Holy Grail, with the scene where the peasant Dennis berates King Arthur: “Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for a system of government..”

I had been on a bit of a medieval binge-watch of late, having seen a number of versions of the Joan of Arc story for my GirlsWithGuns.org site. So I was quite looking forward to this, intrigued by the concept of the dual stories, and the setting in an era not too far away from the Maid of Orleans. The results, however, are hugely disappointing. Kinski as Roland could potentially have worked, even in a deconstruction of the hero, in a similar way to Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972). This lumpy mess can’t even succeed as a spectacle.