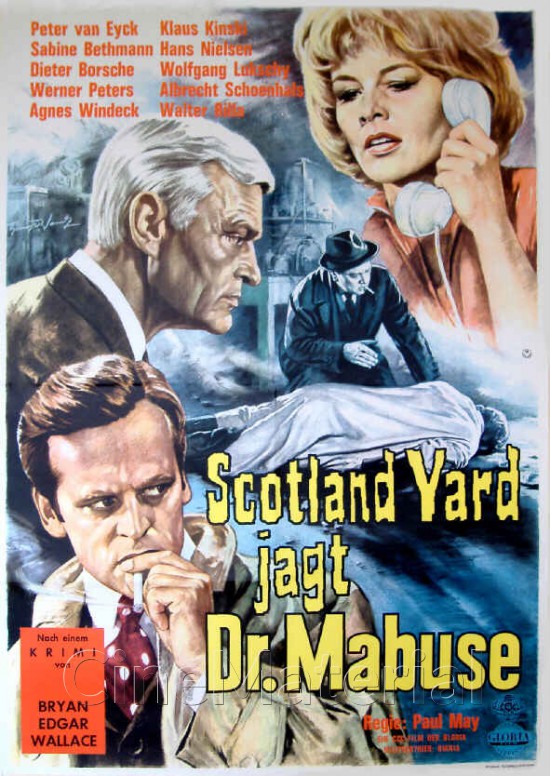

Dir: Paul May

Star: Peter van Eyck, Dieter Borsche, Werner Peters, Klaus Kinski

Dr. Mabuse is best known through the Fritz Lang movies. Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, but in the sixties, the character was revived for six films made by the Berlin company, CCC Film. Some were remakes, in particular 1962’s version of Testament, which starred Gert Fröbe of Goldfinger fame – though not as a villain! But others used the character in other settings, such as this, the fourth entry, based on a novel by Bryan Wallace, who was the son of the more famous Edgar. Here, Mabuse is actually dead, but his role has been adopted by the head of the lunatic asylum where he was confined, Professor Pohland. His plan involves liberating an electronics specialist, George Cockstone (Borsche), to work on a mind-control device which can implant suggestions in virtually anyone’s mind, that they are powerless to resist. When strange cases start to occur as a result, such as a postman murdering a man to whom he is delivered a package, they are investigated by German detective Inspector Vulpius (Peters).

However, once crimes start also to occur in England, the full force of Scotland Yard comes in to assist, led by Major Bill Tern (van Eyck), who was originally responsible for putting Cockstone away. Mabuse/Pohland continues his plan, and the move to England was for a specific purpose, since with the aid of the mind-control device, he accumulates an entire cabinet’s worth of high-ranking citizens, from the police commissioner through to royalty. As the villain expounds, “I’ve summoned you all here, for the express purpose of assisting me to halt the decay of the country, to bring back the glory of the empire and to bring new leadership.” Among those abducted are Vulpius and Inspector Joe Rank (Kinski), and they kidnap Tern with the intent of killing him, and deraoling the investigation. But it turns out that Vulpius, as well as Tern’s elderly mother, have something that renders them impervious to the mind-control device, and which holds the key to Tern defeating Mabuse’s spiritual successor and his quest for global, or at least Anglo, domination.

It’s quite an entertaining piece of hokum, even if the concept at the core is dubious; the mind control works only until the subject falls asleep, so the suggestion must be reinforced every day, which has got to become problematic as the circle of the hypnotized grows, apparently exponentially. The connection to Mabuse is tenuous at best, though this does mean you don’t have to have seen any of the previous entries to appreciate this one. On the other hand, the characters are memorable and quirky, particularly Tern’s mother, who appears to be several steps ahead of the “professional” detectives in terms of figuring out what’s going on, thanks to her encyclopedic knowledge of crimi. I also note a significant plot-point is a robbery of the Glasgow-London train. Either this was eerily prescient or turnaround on production was remarkably fast, because the real Great Train Robbery took place in August 1963, and the film came out in German cinemas the following month.

It’s quite an entertaining piece of hokum, even if the concept at the core is dubious; the mind control works only until the subject falls asleep, so the suggestion must be reinforced every day, which has got to become problematic as the circle of the hypnotized grows, apparently exponentially. The connection to Mabuse is tenuous at best, though this does mean you don’t have to have seen any of the previous entries to appreciate this one. On the other hand, the characters are memorable and quirky, particularly Tern’s mother, who appears to be several steps ahead of the “professional” detectives in terms of figuring out what’s going on, thanks to her encyclopedic knowledge of crimi. I also note a significant plot-point is a robbery of the Glasgow-London train. Either this was eerily prescient or turnaround on production was remarkably fast, because the real Great Train Robbery took place in August 1963, and the film came out in German cinemas the following month.

Kinski’s role is relatively minor – more than a cameo, yet you’d be hard pushed to call it a significant supporting role – and he’s positively restrained by the standards of even his later work in the genre. It might have been more interesting, from a casting point of view, to have Kinski play the role of Cockstone since, at least in Wallace’s original novel, published the previous year, he appears to have been the main protagonist rather than operating largely as a minion. Indeed, that version of Cockstone has something of a Mabuse-esque quality to it, and I’d like to have seen what Kinski could have done with the role of a megalomaniacal villain, rather than what is, if truth be told, a bland and colorless police officer. The film, notably, also drops the anti-socialist theme of the book, in which Cockstone offered his device and its potential to the Communist party! Hey, there was a Cold War on, y’know… If not what you’d call memorable, it does keep moving at a good pace, and succeeds in its apparent goals, even if those never seem any more ambitious than achieving an adequate degree of competence.