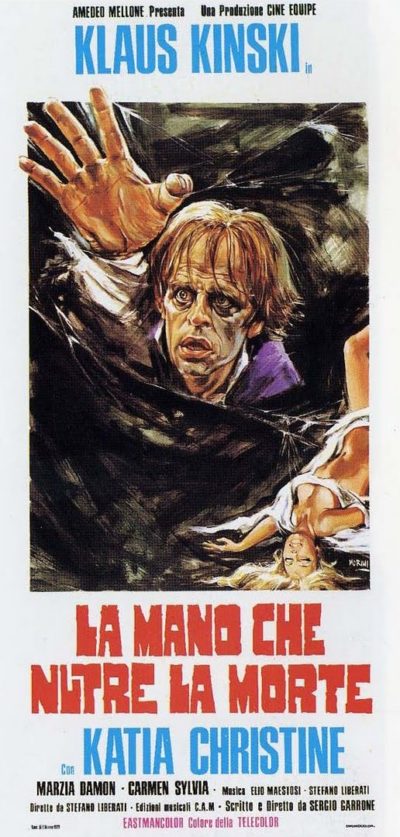

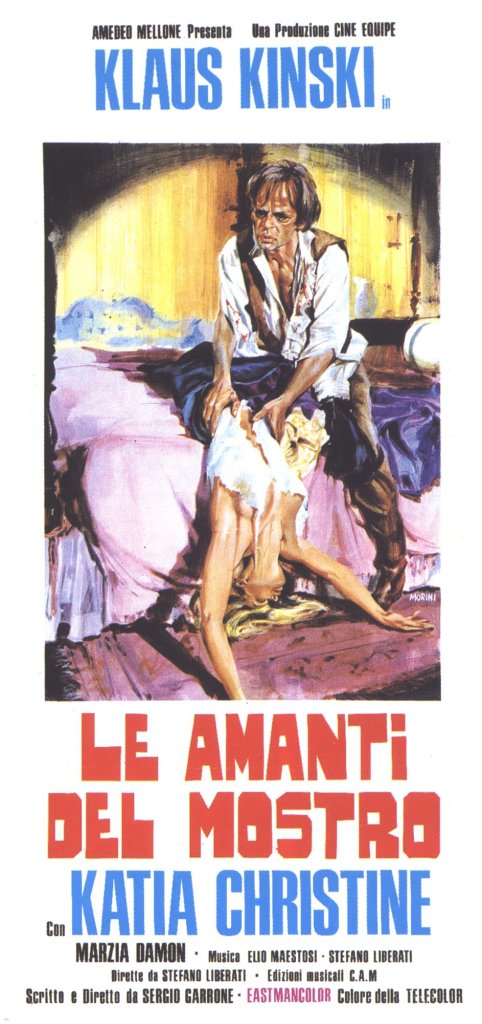

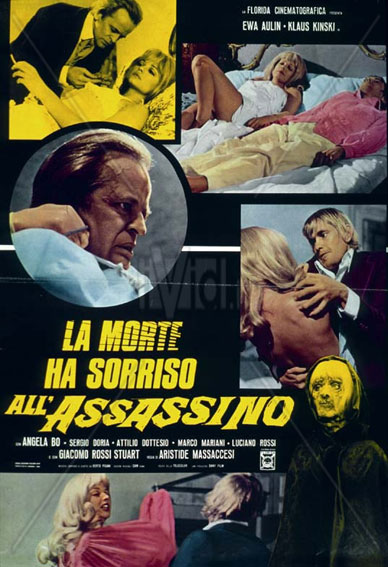

Dir: Sergio Garrone

Star: Klaus Kinski, Katia Christine, Marzia Damon, Carmen Silva

a.k.a. La mano che nutre la morte and Evil Face

According to Wikipedia, this came about after director Garrone was introduced to Turkish producer Şakir V. Sözen, who offered the use of a large villa as a location, in exchange for casting actor Ayhan Işık. Rather than making the planned single film in six weeks, Sözen suggested using it to make two films in eight. Garrone agreed, and so was born this and Lover of the Monster, with which Hand shares much of the same cast and crew – some of the footage shot turns up in both as well. Which makes sense, since the plots overlap enough to have caused confusion over the years. In both, Kinski plays mad scientist Nijinski – there, a mere Doctor, now he has been upgraded to professorial status – who lives on a remote country estate with his wife, and carries on the dubious medical experiments started by his late father-in-law, Baron Rassimov.

The desired outcome is different, however. Where Monster was somewhere between Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, this one is a cross of Frankenstein and Les yeux sans visage. For Professor Nijinski has been experimenting in an effort to repair the damage done to his wife Tanja (Christine), who was badly burned in a fire. As a result, she has become a recluse who rarely ventures out, and only does so wearing a veil. Her husband has been predating the local countryside for subjects, with the help of his mute minion, but fortune smiles on him when a carriage accident literally drops newlywed couple Alex (Işık) and Masha (also Christine) on his doorstep. While they recover from their injuries, they stay in Nijinski’s house, alongside two other women. Katia (Damon) is supposedly writing a book about the Baron, but is actually investigating the disappearance of her sister, while Sonia (Silva) is a whore, bought onto the estate as an unwitting source of spare parts.

That both Masha and Tanja are played by the same actress, more or less tells you where the rest of the film is going to go. We’d worked out how it was going to end quite some time in advance, and the movie did not disappoint in this aspect, shall we say. There were some unexpected diversions along the way, however, not least the lesbian canoodling between Katia and Sonia – even if the post-canoodle cuddle is rudely interrupted by the minion. We were also impressed with the use of a tuning fork to manipulate said henchmen, suggesting that the Professor’s research has perhaps also gone into the area of mind-control.

That both Masha and Tanja are played by the same actress, more or less tells you where the rest of the film is going to go. We’d worked out how it was going to end quite some time in advance, and the movie did not disappoint in this aspect, shall we say. There were some unexpected diversions along the way, however, not least the lesbian canoodling between Katia and Sonia – even if the post-canoodle cuddle is rudely interrupted by the minion. We were also impressed with the use of a tuning fork to manipulate said henchmen, suggesting that the Professor’s research has perhaps also gone into the area of mind-control.

Even though it was close to four years ago that I watched Monster, the similarities are striking, and there were times where it would have been very easy to forget which movie you were watching, they share so many elements. It definitely evokes a sense of deja vu, in its purest sense. Hand is perhaps – it has been four years! – slightly more Gothic in tone. I feel like its closest cousins might be the Hammer films of the early seventies, when the British studio started adding more exploitative aspects to its traditional story elements. There’s a great deal of creeping around corridors by candlelight, with the heroines typically wearing the kind of floaty nightgown, no-one ever wears outside of period horror movies.

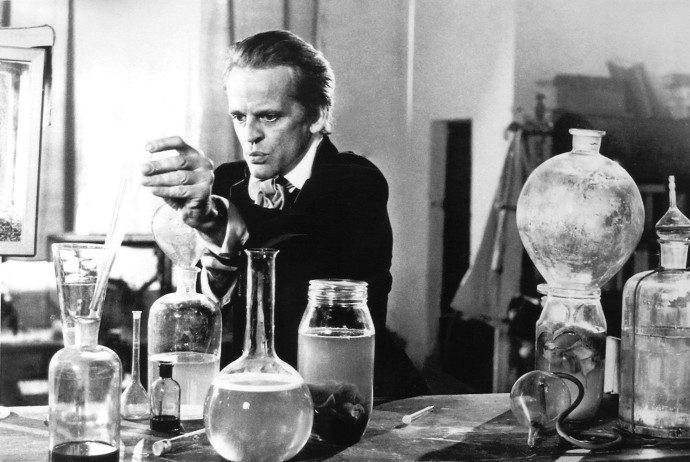

The surgical sequences are similarly lengthy (though it does appear there may have been a stand-in for Kinski during them), and surprisingly gory. The effects were by Carlo Rambaldi, who worked on the two Andy Warhol films, Blood for Dracula and Flesh For Frankenstein, the same year as this. He would take home the first of his three Academy Awards for visual effect three years later, for his work on King Kong, also winning for Alien and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Rambaldi designing the title character in the latter. Safe to say, creating that lovable alien is quite some distance from fabricating the face-flaying which provides this film’s most memorable moment.

The plot does offer some twists in the later stages, and it turns out that Prof. Nijinski perhaps isn’t such an unrepentant villain as he initially appeared. His harvesting of female skin donors from the countryside nearby is largely driven by a devotion to and love for Tanja, which is almost touching (if you squint at it from the right angle, under appropriately subdued lighting). It’s bordering on poignant when the carpet is pulled out from under his affection, with Tanja deciding instead to take advantage of the obvious opportunity presented by her new looks. However, other aspects of the script don’t work as well, such as the police investigation into Nijinski, that gets early screen time, then is all but forgotten in the second half.

Kinski is solid, effective, and by his standards, very restrained: the film still entertains almost in direct proportion to the amount of Klaus present. Which as a rule of thumb, means the second half is likely superior, as the movie settles down on him and Tanja. The first half seems to suffer from a lack of focus: at various times, it feels like the heroes are going to be Alex and Masha, then Katia and her boyfriend. To be honest, they’re nowhere near as interesting characters as the Professor and his veiled spouse. The writer should have concentrated on their story, and kept the others more firmly in the supporting roles they deserve.

The rest of the technical elements are as solid as they were in Monster, with good use being made of the countryside locations. I think I preferred this one to its partner. Both Kinski and Christine deliver better performances, and there’s something almost Shakespearean about the tragic way this ends. The pacing during the first half could certainly do with some tightening up, yet this one eventually proved able to sustain even my wife’s interest – and she is usually a good bellwether that a Kinski movie is decent quality!

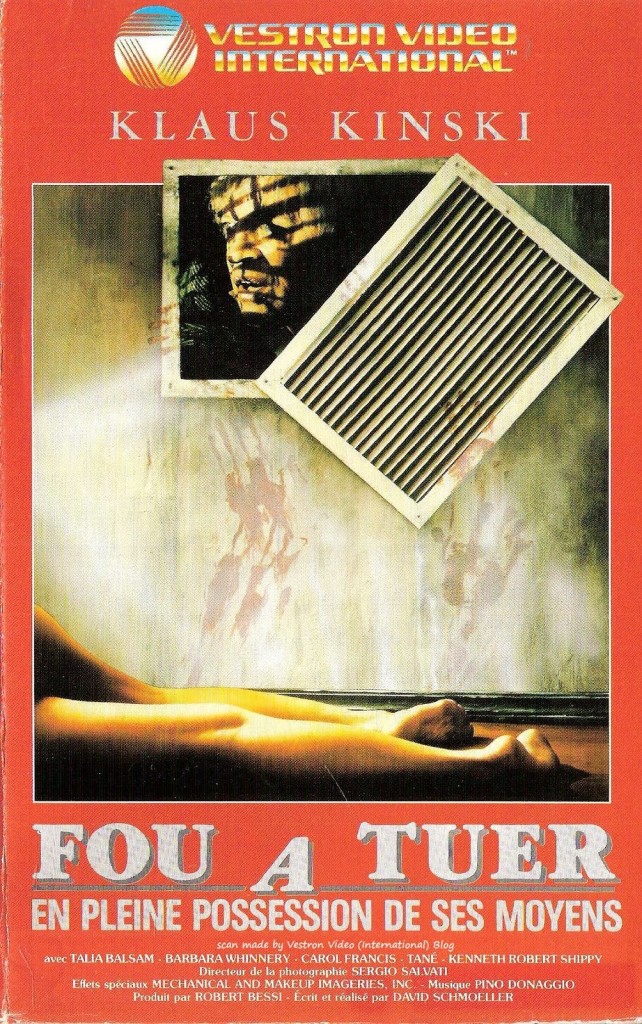

You’ll notice that Klaus’s character only receives a passing mention. That’s because, despite his co-star billing with Aulin, his role is largely incidental. He has a sideline, working to discover the secret of life in a basement laboratory with his mute assistant, and a medallion worn by Greta appears to have provided a breakthrough. One imagines he sensed something was up when he was able to stab her in the eyeball with a pin, and not even receive a blink; that, along with the odd scar on the side of her neck where the IV tube of elixir went in. Anyway, he successfully revives his own test subject, only to be offed, along with his assistant, by (presumably) the same person who killed the maid. Exit Mr. Kinski, before the half-way point has been reached, though he’d return for another Massaccesi movie later in the year, Heroes in Hell.

You’ll notice that Klaus’s character only receives a passing mention. That’s because, despite his co-star billing with Aulin, his role is largely incidental. He has a sideline, working to discover the secret of life in a basement laboratory with his mute assistant, and a medallion worn by Greta appears to have provided a breakthrough. One imagines he sensed something was up when he was able to stab her in the eyeball with a pin, and not even receive a blink; that, along with the odd scar on the side of her neck where the IV tube of elixir went in. Anyway, he successfully revives his own test subject, only to be offed, along with his assistant, by (presumably) the same person who killed the maid. Exit Mr. Kinski, before the half-way point has been reached, though he’d return for another Massaccesi movie later in the year, Heroes in Hell.