Dir: Fernando Colomo

Dir: Fernando Colomo

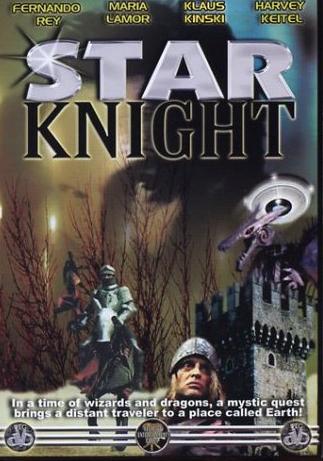

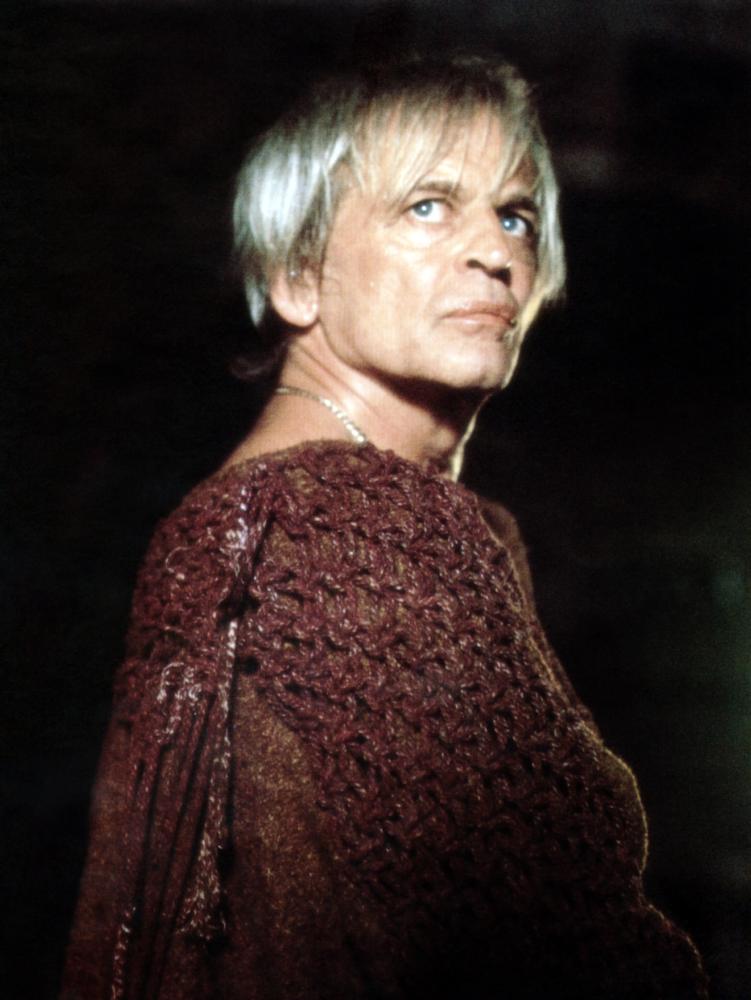

Star: Harvey Keitel, Maria Lamor, Miguel Bosé, Klaus Kinski

a.k.a. Star Knight

Well, it’s certainly different, that’s for sure. Not least in its casting. Kinski as an alchemist, I can get my brain around – it’s really just a Spanish, historical variant on the mad scientist role he has played often enough. But there was apparently once a world in which the producers thought, “We need a medieval knight. I’ll tell you who we should get: Harvey Keitel.” Admittedly, this was during the eighties, when Keitel was largely floundering in obscurity; the previous year, in Nemo, he had basically played Zorro, so I suspect he was operating in “Don’t send me the script, just send me the check” mode. Not that he’s terrible, it has to be said. Just that watching the Bad Lieutenant riding around in armor on horseback in a film which occasionally teeters into Holy Grail territory, is not what I expected. Chalk up another of the odd pleasures I’ve experienced, courtesy of Project Kinski!

This is not exactly a common genre either, that of medieval sci-fi. A “dragon” is pillaging the land, culminating in it stealing away the king’s daughter, Princess Alba (Lamor). The king’s leading knight, the presumably ironically-named Klever (Keitel), goes off to try and rescue her, having been promised her hand in marriage and half the kingdom if he succeeds. But the only person who has kinda worked out what’s going on is alchemist Boecius (Kinski). He has taken a break from his research towards an elixir of eternal life, along with his work as the king’s physician, and knows that the dragon is a UFO, piloted by a humanoid and telepathic alien, Ix (Bosé), possessing a haircut which positively screams “mid-eighties.” Ix’s armor is actually a space-suit, protecting him from earth’s atmosphere, but that hasn’t stopped him from falling in love with Alba, and vice-versa. Will this tale of inter-stellar love have a happy ending?

Arthur C. Clarke once wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” and that’s one of the concept at the heart of this film. I like the idea that people would interpret extra-terrestrial phenomena, in a way which fits their existing world view – in this case, in terms of dragons or demons. Boecius’s capacity to grasp the situation leads him to be accused of being in league with the devil, leading to his arrest – though curiously (albeit fortunately for the plot), rather than being burned at the stake for witchcraft, he is still allowed to accompany Klever as he heads off on his mission. It’s not often that Klaus gets to play a character who is easily the sharpest tool in the box, and it’s a shame that he isn’t given more to do, such as interface with Ix to a greater degree. Instead, he literally sits around with his hands tied for most of the second half.

But there is a fair bit to enjoy in the rest of proceedings, though it’s hard to be sure how seriously we are meant to take proceedings. I mentioned the Holy Grail above, and its most obvious influence is the Green (rather than Black) Knight character, who guards a bridge, refusing to let everyone pass – but in reality, is completely incompetent and incapable of stopping anybody. While I understand the aim was comic relief, he seems to have strayed in from a completely different film, and instead does a pretty good job of destroying the “magical realism” atmosphere which is otherwise being built up nicely. Helping that out is Jose Nieto’s score, which is genuinely impressive and evocative – like the Green Knight, it appears to have strayed in from another movie, only in the soundtrack’s case, it’s a much better one.

But there is a fair bit to enjoy in the rest of proceedings, though it’s hard to be sure how seriously we are meant to take proceedings. I mentioned the Holy Grail above, and its most obvious influence is the Green (rather than Black) Knight character, who guards a bridge, refusing to let everyone pass – but in reality, is completely incompetent and incapable of stopping anybody. While I understand the aim was comic relief, he seems to have strayed in from a completely different film, and instead does a pretty good job of destroying the “magical realism” atmosphere which is otherwise being built up nicely. Helping that out is Jose Nieto’s score, which is genuinely impressive and evocative – like the Green Knight, it appears to have strayed in from another movie, only in the soundtrack’s case, it’s a much better one.

To be honest, the climax of the film is implausible, even by the low standards set over the first 80 minutes. It relies on Boecius having developed an elixir which, never minding working on humans, is also capable of affecting aliens to whom our atmosphere is lethal, and presumably have a radically different physiology. But I can’t say I minded too much, being willing to cut the film some slack due to its original approach and theme. Still, it’s shaky enough that I was surprised to discover it reportedly received an American theatrical release in 1986: I guess standards have dropped significantly over the last two decades. This is fairly readily available now, having apparently fallen into the public domain, and as a result shows up on some of those big box sets, with titles like Sci-Fi Invasion 50 Movie Pack. You can even find the full thing on YouTube, albeit in a version which isn’t just dubbed, it’s also slightly out of synch. However, I can’t claim with a straight face that this impacted my enjoyment of it too much!