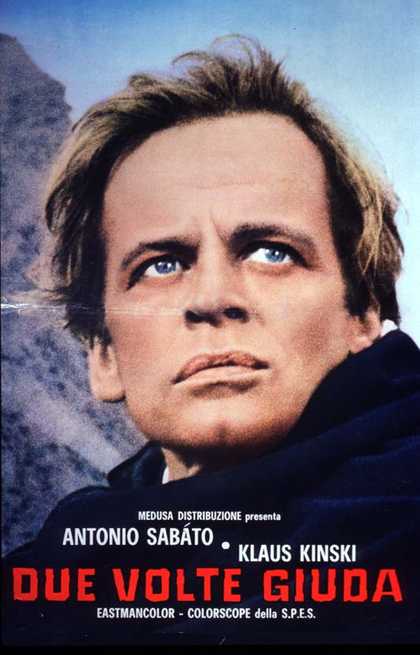

Dir: Guido Zurli

Star: George Martin, Andrea Aureli, Paolo Carlini, Klaus Kinski

a.k.a. Mister Ten Percent, Psychopath, Sigpress contro Scotland Yard

This begins with opening credits which have, in the background, a hairy George Martin bouncing, without his shirt on a trampoline. It feels a lot longer than the four minutes it lasts, and I couldn’t help thinking I’d rather have had Karin Field bouncing topless on a trampoline for four minutes. Hell, I’d probably rather have had Klaus doing the back-flips, purely for bizarreness. I guess the aim is to establish Sigpress (Martin) as an athletic type, and no sooner has he dismounted than he’s being swarmed by beach bunnies, enamored of his physique. We soon also discover his day-job is as a thief, albeit with a twist: he steals jewels, and then ransoms them back, either to their owner or to the insurance company, for a cut of their value. Hence the title of the film, which translates as Mister Ten Percent – Chicks and Big Bucks. He is being hunted by Inspector Bennett (Carlini) of Scotland Yard, whom Sigpress delights in taunting over the phone.

After an amusing opening caper, where Sigpress robs some robbers, disguised as James Bond, the main focus is on a jewel, the Eye of Allah, belonging to dubious businessman Thamistokles Nyorkos (Aureli), who is unable to come and pick it up from London due to outstanding legal issues. The gem is sent on the boat-train to Paris, under escort of Lloyds’ agents and Inspector Bennett, with Sigpress on the train too, pretending to be a journalist doing a feature on Bennett. But someone else swoops in and steals the gem from under their noses. Turns out it was actually an associate working for Nyorkos – this way, he’ll get both the gem, for his private collection, and the insurance payout. Is that going to stop Sigpress? Of course not. However, he’s not the only person with designs on the gem, as Nyorkos finds out, when he is attacked and shot on the way back from Paris.

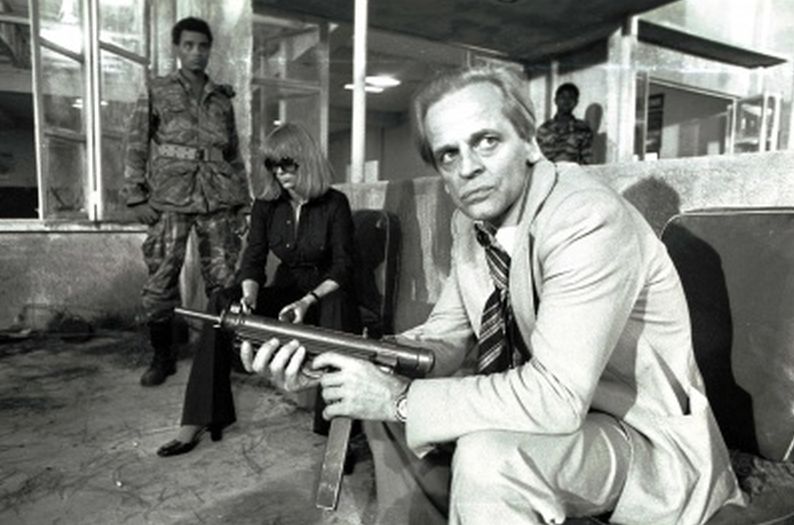

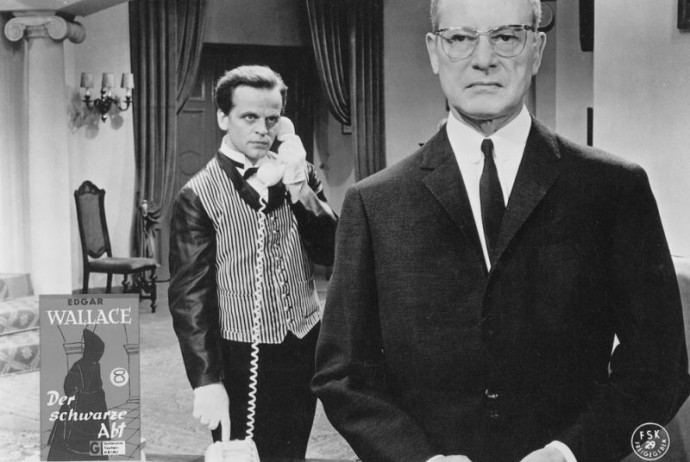

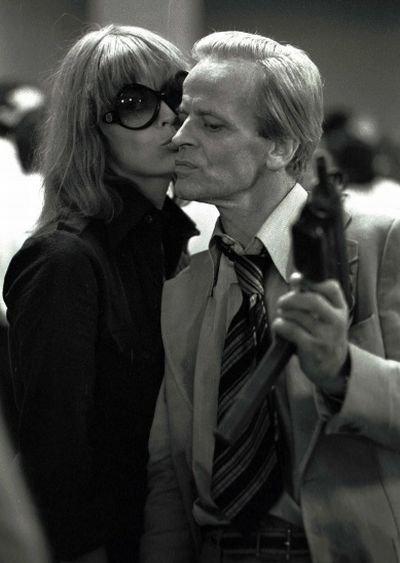

What does Klaus have to do with all these continental shenanigans, I hear you ask? Good question. He plays Periwinkle – I’m fairly sure the first and last time Kinski played a character named after a flower. Or possibly a shellfish. Or a Crayola crayon. Regardless, he’s Sigpress’s manservant, whose duties include answering the phone and, as depicted at the top of this review, bludgeoning British bobbies into unconsciousness. As this would suggest, he’s entirely aware of his boss’s clandestine activities, this mugging occurring as part of a trip to a seedy nightclub, where Sigpress hopes to gather intel on the jewel, by taking on the identity of one of the collaborators, who is knocked out and whom Periwinkle is left to guard, eventually drawing the attention of the police officer in question.

This is followed by Sigpress going for a stroll through swingin’ London, which includes another nod to everyone’s #1 secret agent [You Only Live Twice had apparently just come out], that is a decent summary of the lighthearted approach taken here. The film at its best when its playing with the conventions of the genre like this, and twisting them in an occasionally surreal fashion. For example, when in Paris, Nyorkos and his wife go out to a venue that seems to offer dinner and dancing, as well as striptease and casual prostitution. Bennett and Sigpress are both there, the former declining an offer of female companionship by deadpanning, “I’m afraid you’d be wasting your time. You don’t know me, but I strangle women, and with their own belts.” The scene ends with the nightclub customers dancing, with moderate enthusiasm, to what I swear appears to be a jazzy Ride of the Valkyries interpretation.

This is followed by Sigpress going for a stroll through swingin’ London, which includes another nod to everyone’s #1 secret agent [You Only Live Twice had apparently just come out], that is a decent summary of the lighthearted approach taken here. The film at its best when its playing with the conventions of the genre like this, and twisting them in an occasionally surreal fashion. For example, when in Paris, Nyorkos and his wife go out to a venue that seems to offer dinner and dancing, as well as striptease and casual prostitution. Bennett and Sigpress are both there, the former declining an offer of female companionship by deadpanning, “I’m afraid you’d be wasting your time. You don’t know me, but I strangle women, and with their own belts.” The scene ends with the nightclub customers dancing, with moderate enthusiasm, to what I swear appears to be a jazzy Ride of the Valkyries interpretation.

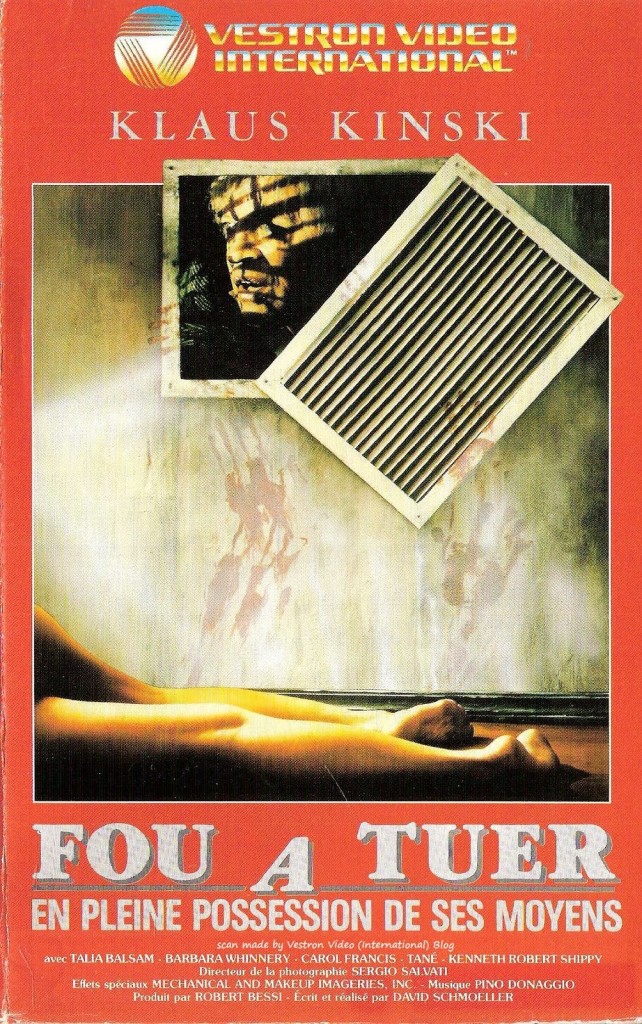

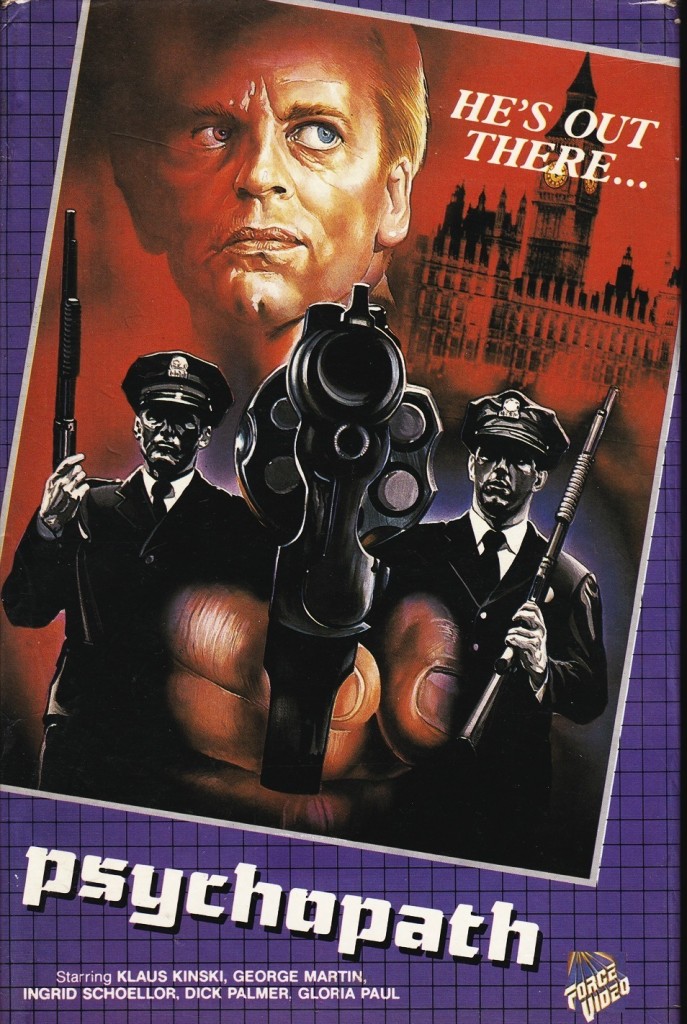

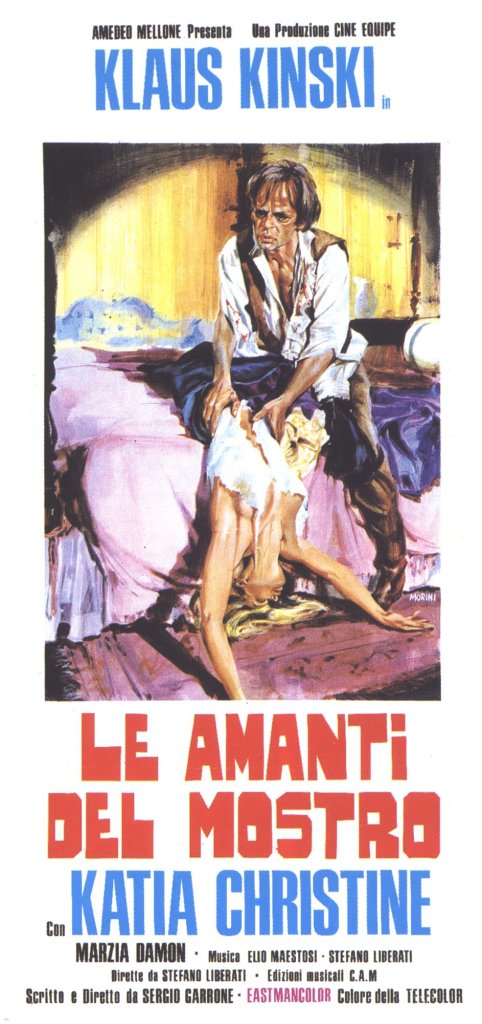

It would be preferable if there was more Kinski. Despite the wildly misleading cover, above right [wrong in just about every details, although the biggest question would be, where the hell did they get the title, Psychopath?], he is very much a supporting character. Once Sigpress goes off to France, Periwinkle is virtually out of the movie, although he does make a crucial reappearance at the end to get his boss off the hook, just when Bennett thinks he has finally got his man, That’s a shame since the pair make an entertaining double-act, with Kinski deadpanning his way through scenes in dogged support of Martin. There’s almost an element of Inspector Clouseau and Cato here, though Sigpress is a good deal more competent, obviously. It feels like they were trying to start a franchise here, but given the lack of follow-up, it appears this initial entry did not meet with sufficient success to justify it. It could still work in the modern era, and though certain elements are dated, the core idea is strong: you could see, perhaps, Jason Statham or Clive Owen taking on the lead role, though I’m at a loss to figure out who might replace Kinski [true for many of his performances!].

I enjoyed this, perhaps in part because I went in with no real expectations or foreknowledge – though heaven knows what I’d have thought had my expectations been based on that sleeve! After what feels like a fairly long sequence of films where the non-Kinski elements have been disappointing, it’s a breath of fresh air to find one whose entertainment value is not solely dependent on Klaus’s presence. He made no secret of being willing to appear in just about anything for the right price, and the results often reflect his lack of quality control. However, this isn’t one of those, providing a frothy Euro-romp that is definitely aware of its own silliness, and has withstood the test of time rather well.

There’s good reason for this, because the film had as many as six different directors at various stages of proceedings.

There’s good reason for this, because the film had as many as six different directors at various stages of proceedings.

This may help explain why such a glossy genre piece was submitted as Israel’s entry for the ‘Best Foreign Film’ at the 50th Academy Awards, an honor not usually given to such a… Well, I could use the term “jingoistic piece of cinema,” but let’s go with “straightforward action flicks.” It actually made it as far as the final five nominations, alongside Luis Bunuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire, but both lost out to France’s now largely-forgotten Madame Rosa. [I note that among the other national entries that year were Wim Wenders’ The American Friend and Paul Verhoeven’s Soldier of Orange] There were two versions of the film made: a wholly English-language one for the international market, and the one seen here, which is told in a variety of languages, including English, German, Hebrew and Arabic. Also worth mentioning, two years later director Golan would team up with cousin Yoran Globus to buy Cannon Films, one of the most prolific production companies of the eighties.

This may help explain why such a glossy genre piece was submitted as Israel’s entry for the ‘Best Foreign Film’ at the 50th Academy Awards, an honor not usually given to such a… Well, I could use the term “jingoistic piece of cinema,” but let’s go with “straightforward action flicks.” It actually made it as far as the final five nominations, alongside Luis Bunuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire, but both lost out to France’s now largely-forgotten Madame Rosa. [I note that among the other national entries that year were Wim Wenders’ The American Friend and Paul Verhoeven’s Soldier of Orange] There were two versions of the film made: a wholly English-language one for the international market, and the one seen here, which is told in a variety of languages, including English, German, Hebrew and Arabic. Also worth mentioning, two years later director Golan would team up with cousin Yoran Globus to buy Cannon Films, one of the most prolific production companies of the eighties.