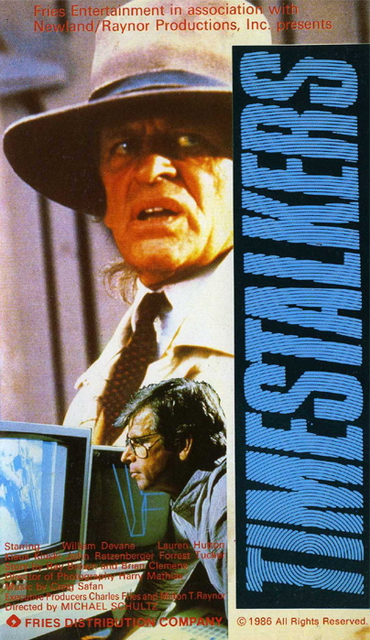

Dir: Michael Schultz

Star: William Devane, Lauren Hutton, Klaus Kinski, John Ratzenberger

This TV movie first aired on CBS in March 1987, and more or less combines two standard Kinski tropes: mad scientist and black-hearted gunslinger. Things kick off when history professor and Western enthusiast Scott McKenzie (Devane) buys an old photo, and realizes that the 1886 image contains a man wielding a .357 Magnum – a gun which dates from almost a century after the photo was taken. He writes a paper on the picture, challenging his class to come up with a solution, and is subsequently visited by Georgia Crawford (Hutton).

This TV movie first aired on CBS in March 1987, and more or less combines two standard Kinski tropes: mad scientist and black-hearted gunslinger. Things kick off when history professor and Western enthusiast Scott McKenzie (Devane) buys an old photo, and realizes that the 1886 image contains a man wielding a .357 Magnum – a gun which dates from almost a century after the photo was taken. He writes a paper on the picture, challenging his class to come up with a solution, and is subsequently visited by Georgia Crawford (Hutton).

She reveals that she is a time-traveler from 600 years into the future, and is hunting the man in the picture, Dr. Joseph Cole (Kinski). He worked with her father inventing the time-travel device, but when Crawford tried to stop him from changing history, Cole stole the device and vanished – it now appears, going back to 1886. What exactly was his purpose? Bipping back and forth in time, Scott and Georgia try to figure that out, and how to stop Cole before he can carry out his plan to alter the future by changing the past.

As with most films about time-travel, it’s best not to stare too closely at the plot, because the paradoxes that result are almost insurmountable. [Spoilers follow, as a necessary result] If Cole is going back to kill the ancestor of the man who helped invent the time-travel gizmo, doesn’t that mean it won’t be invented? If that’s the case, how could Cole then go back in time to begin with? Also, why bother going back 700 years? That’s like trying to stop Hitler by finding his ancestor in 12th-century Germany. Why not just pop back a week and poison Crawford’s coffee? And don’t even get me started on the ending, which can only by explained by a complete and willful ignorance of the works of Ray Bradbury. Let’s just say, I doubt it turns out well.

That’s a little disappointing, considering this was written by Brain Clemens, who is quite a renowned figure in genre media. He wrote the original pilot for The Avengers (younger readers: the seminal 1960’s TV series, not the PPV comic-book franchise) and also wrote and directed Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter, one of the more under-rated entries in the late Hammer horror canon. Here, he may have been limited, since he’s supposedly working from a source story – Ray Brown’s The Tintype, though I add the caveat since I’ve been unable to find out any significant information regarding it, or indeed Brown, who has no Wikipedia entry or even other IMDB credits.

This definitely appears to have been influential on a number of later, larger works: the most obvious are Timecop, with one batch of time-travellers, trying to stop another from screwing up the timeline, and Back to the Future, Part III, which also focused on time-travel to the Old West. However, those wouldn’t be released for another seven and three years respectively, so let’s give Timestalkers credit where it’s due. On the other hand, there are a few elements that are horribly dated: most obvious is a sequence where they visit another Old West collector, seeking information. He hauls a song out of his database, and plays it for them, accompanied by 16-bit graphics that may have been cutting-edge in 1987, but are now wrist-cuttingly awful.

This definitely appears to have been influential on a number of later, larger works: the most obvious are Timecop, with one batch of time-travellers, trying to stop another from screwing up the timeline, and Back to the Future, Part III, which also focused on time-travel to the Old West. However, those wouldn’t be released for another seven and three years respectively, so let’s give Timestalkers credit where it’s due. On the other hand, there are a few elements that are horribly dated: most obvious is a sequence where they visit another Old West collector, seeking information. He hauls a song out of his database, and plays it for them, accompanied by 16-bit graphics that may have been cutting-edge in 1987, but are now wrist-cuttingly awful.

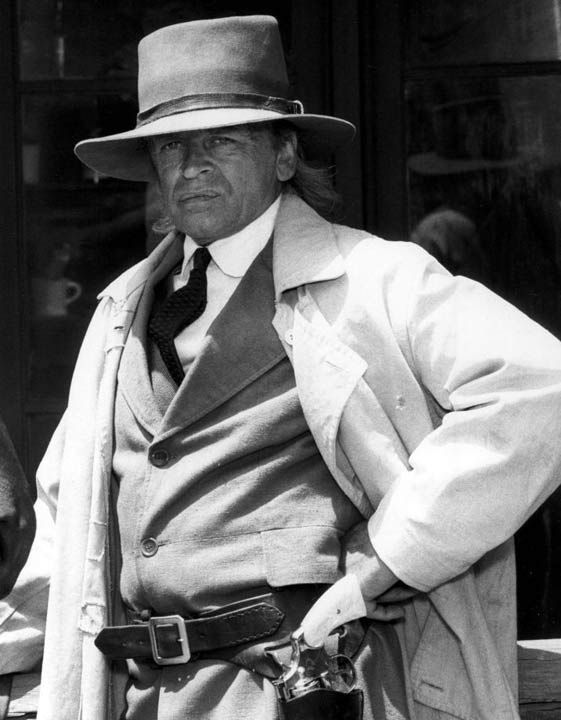

Casting Kinski in a TVM is a bit like the cops sending a battalion of tanks to handle a domestic dispute: it’s simply overkill, considering the amount of restraint required for the medium. Whether by chance or design, Kinski doesn’t actually get to interact much with the other main characters. There’s an argument with his colleague Crawford that certainly demonstrates Klaus’s fire, but for much of the rest of the time, he’s roaming the 19th century on his quest, all by himself. However, he does get to do a decentish Travis Bickle impersonation, staring into the mirror, and in story terms, I liked how he gets into an army base, by traveling back to before it was built, passing through where security will be, then coming back. I also enjoyed the scene in which Cole pulls off a carjacking that would look impressive in Grand Theft Auto V, shoving the owner out the door as it whizzes along, with a cheery “Thanks for the lift, mister.”

Actually, that quote provides a fairly appropriate summary of the film as a whole. It whizzes along, zipping from century to century in such a way that the flaws are somehat hidden, before coming to a moderately-exciting climax as the US President heads through the desert, and right into an ambush. This is where McKenzie’s Western-style training – none too subtly foreshadowed early, while the plot is ambling its way towards significance – pays off, though I do have to question his convenient, Annie Oakley-esque accuracy while on horseback, which is not addressed during the previous going. That’s the main flaw here: a script definitely in need of at least a couple more rewrites before being ready from prime-time, particularly occupying such a logically dangerous area as time-travel.

But by the low standards of made-for-television movies, I’ve seen much worse, and the performances are better than you normally get in such things. Devane sells the concepts involved with enough enthusiasm to convince the audience, if they’re prepared to squint a little bit, although former model Hutton is less than entirely convincing as A Scientist. Kinski is perfectly fine as an evil antagonist, but you certainly don’t get the sense he was taxed or challenged by anything here, although at least I could locate no reports of issues or problems during filming. The film is currently on Youtube. I can’t say how long it might last, but it has been up since February this year, and would seem to have a decent shot as surviving, so here you go…

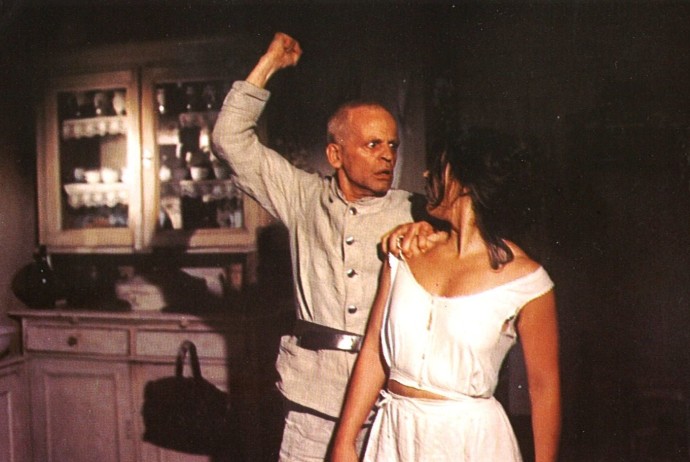

The tipping-point, however, is the realization that Marie may be having an affair with another soldier, higher in rank and – let’s be honest – physical appeal, charm and sanity, while he’s at it. This sends Woyzeck right over the edge, and he stabs her to death while they’re out on a walk. He takes refuge in a local inn, though his blood-stained appearance gives him away. The film ends with the discovery of Marie’s body, and a final caption, stating that it’s been some time since they’ve had such a good murder. I suppose this is some kind of spoiler, but it’s in such little doubt that this is where the movie is heading, that it barely counts.

The tipping-point, however, is the realization that Marie may be having an affair with another soldier, higher in rank and – let’s be honest – physical appeal, charm and sanity, while he’s at it. This sends Woyzeck right over the edge, and he stabs her to death while they’re out on a walk. He takes refuge in a local inn, though his blood-stained appearance gives him away. The film ends with the discovery of Marie’s body, and a final caption, stating that it’s been some time since they’ve had such a good murder. I suppose this is some kind of spoiler, but it’s in such little doubt that this is where the movie is heading, that it barely counts.

It is, very much, a loving homage to F.W. Murnau’s original, though the expiration of copyright allows Herzog to use the actual names of the characters, rather than, as Murnau did, make them up in a (failed) attempt to avoid a lawsuit. The make-up is almost identical, not just on the vampire, but on Lucy Harker (Adjani), who has the same pasty-pale pancake on her face and perpetually-concerned expression as Ellen Hutter in the original – see the illustration on the left. Indeed, sometimes the only way to tell her and Dracula apart is to look for the pointy teeth.

It is, very much, a loving homage to F.W. Murnau’s original, though the expiration of copyright allows Herzog to use the actual names of the characters, rather than, as Murnau did, make them up in a (failed) attempt to avoid a lawsuit. The make-up is almost identical, not just on the vampire, but on Lucy Harker (Adjani), who has the same pasty-pale pancake on her face and perpetually-concerned expression as Ellen Hutter in the original – see the illustration on the left. Indeed, sometimes the only way to tell her and Dracula apart is to look for the pointy teeth.