Dir: Josh Johnson

Star: Klaus Kinski, Debora Caprioglio, Barry Hickey, Diane Salinger

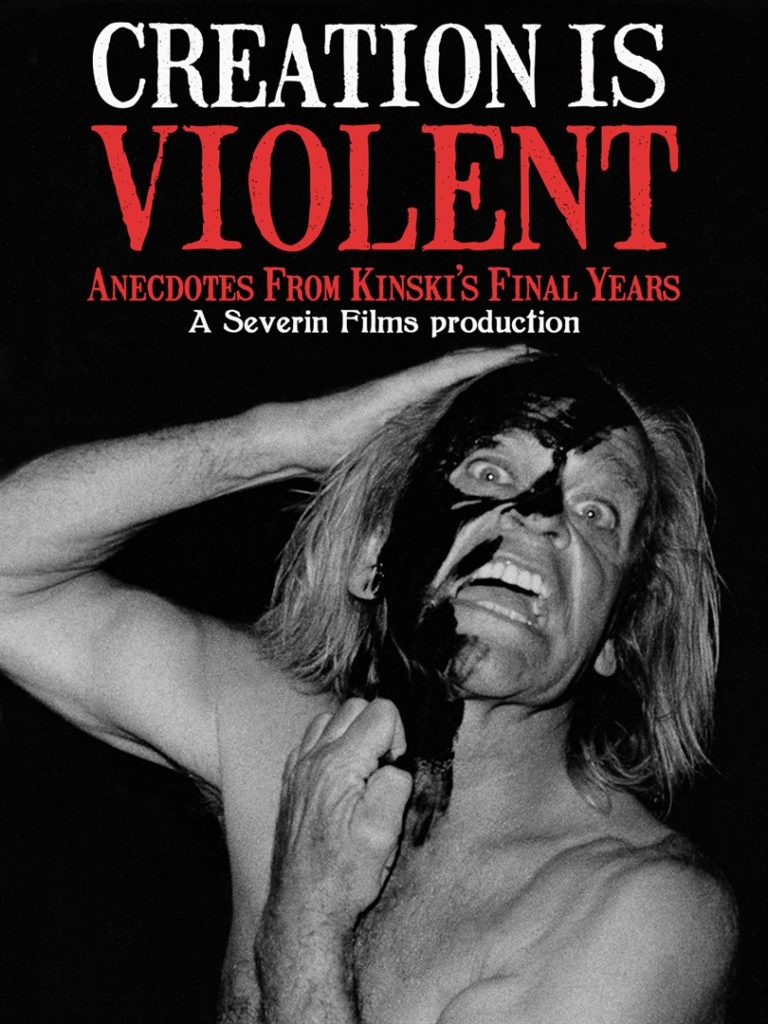

This documentary covers Kinski’s final years, roughly from 1985 through to his death in 1991, roughly in chronological order. Though it concentrates more on particular project during that time, rather than being a comprehensive overview of the period. There’s very little about the making of Cobra Verde (1987) and not even a mention of Grandi Cacciatori (1988). Instead, there is a wealth of detail about Creature (1985), Revenge of the Stolen Stars (1986), Crawlspace (1986), Vampire in Venice (1988) and Paganini (1989), as well as a final segment where they talk to those who knew Klaus when he lived at his remote mountain chalet in Lagunitas, California. The film was originally released as an extra on the BliuRay release by Severin Films of Vampire, but has now made its way onto a number of streaming services as a stand-alone title.

By the time the final credits roll, it feels refreshingly even-handed, even if there are points while it feels like it’s going to topple over into the “Kinski = madman” category for a bit. There’s no doubt that he was a difficult actor to work with, not least because of his legendary hatred for directors. [I wonder if, having experienced the role himself in Paganini, whether he might have mellowed towards them thereafter? Since it was his final film, we’ll never know] Kinski believed they were almost worthless, particularly in terms of providing instructions to him, which he felt was useless. That was only part of the problem: in every area, from costume to dialogue, he was exacting to a fault, and would brook little or no argument on the topic.

There’s any number of anecdotes here, recounted by those who worked with him, which go to prove the point. Gabe Bartalos, who provided special effects on Crawlspace, tells this control complex applied even to a publicity interview on the set, where Kinski refused to speak directly to the interviewer, but insisted on bringing Gabe along as they meandered around the studio, as a focus for Klaus’s answers. Yet there’s a sense of warmth to Bartalos’s comments about Kinski, acknowledging that his tantrums were born of a passion for his art, and that even his dislike of directors is not entirely without merit. In contrast is the opinion of Stefano Spadoni, the production manager on Paganini, who says bluntly, “Klaus Kinski was the worst work experience of my life. I would never do it again, even under torture.”

Some material may be familiar. Personally, a lot of the stories told by Hickey about his experience on Revenge I had heard and documented when writing about the movie. However, I definitely wish I’d seen this when covering Vampire or Paganini, for the stories go a long way to explaining why the end-product in both cases fall so far short of the work obtained from Kinski by Werner Herzog. For example, Vampire in Venice was supposed to take place during carnivale there: with Kinski unavailable until the summer, the production devoted time and money to shooting footage during the event, a body-double standing in for Klaus, complete with bald head, long fingers and cape. Except, the star rejected entirely that look when he arrived on set, rendering it useless. The reactions of co-stars Donald Pleasence and Christopher Plummer toward Kinski are also interesting: the former basically ignored the on-set chaos, while Plummer took a different approach:

At first he put a lot of effort into the movie since he’s a huge professional. His first scenes were the ones of the duel against Kinski, when Plummer shoots and puts a hole in Kinski’s stomach… When we did rehearsal for that scene, Plummer started saying his lines in front of Kinski. Kinski looked at him in an indifferent way because, as I said, he didn’t want to rehearse. Without saying anything, he took his mirror from his pocket, the one he used every day to check his make-up, took a comb, and started combing his hair while Plummer was saying his lines in front of him. And then he answered him while he was still combing his hair, with the same indifferent look. Plummer was flabbergasted and then he burst into laughter. From that moment on he treated the set like a joke. He no longer cared. One day I asked him, “How is it to act with Kinski?” He said, “Well, they’re paying me so much money that I don’t care.”

Luigi Cozzi, FX on Vampire in Venice

The complex relationship of Kinski and women does get some coverage, though none of the fair sex interviewed here could be accused of “dishing the dirt”. Salinger, his co-star in Creature, may have been making her feature debut, but had clearly been forewarned about his reputation, and describes how she dressed in the least sexy way possible for her first meeting with him – to no avail! Again though, both she and Joycelyne Lew from Revenge don’t appear to hold any particular grudge against him, or have experienced anything they felt was particularly abusive. The same cannot perhaps be said of Vampire‘s Barbara De Rossi. Sound engineer Luciano Muratori says he saw Kinski stick his fingers in her vagina during a shot, an assault which sent the young actress running in tears from the set.

On the other hand, we hear quite a lot from Kinski’s girlfriend of several years, Debora Caprioglio, whom he met on the set of Vampire.when she was 18. She speaks about what drew Klaus to the Paganini project: “Just like him, [Paganini] was genius and disorder.” She was with him through the production in which she co-starred, and beyond, including the tumultuous Cannes press conference [of which we only see a segment sadly, top] where Kinski did not respond well to criticism, shall we say. Of their relationship, she says, “He was a very generous man, very loving, very jealous, even too much. He alternated moments of extreme sweetness and calm with moments of rage… In his private life, in his relationship with me, he was very sweet because he wasn’t irascible. You would think that a man like him, with such a peculiar nature, might have been different, but he always had the greatest respect for our relationship, and he was also very protective.”

It’s this which begins to tile the film back towards balance, and leads into the film’s final section, where we hear from people who interacted with Klaus in his everyday life, such as the man who ran the local post office near his chalet. The two appear to have stuck up an unlikely friendship, Klaus sending postcards back and even inviting him to the premier of Paganini in Paris. We also hear from Sara Ellis, a local mountain biker who was the last person to see Klaus alive, going to his home to look over photographs he had taken of her in action, the night before he died of a heart attack. Their accounts ring true, depicting a complex, troubled performer, who did everything at 110%, yet could take pleasure in little things like using the ‘Return to Sender’ stamp. Don’t expect this documentary to provide any easy answers for such a multi-faceted human being. You may well leave with no better understanding than you had before, yet that’s an undeniable part of Klaus’s fascination.