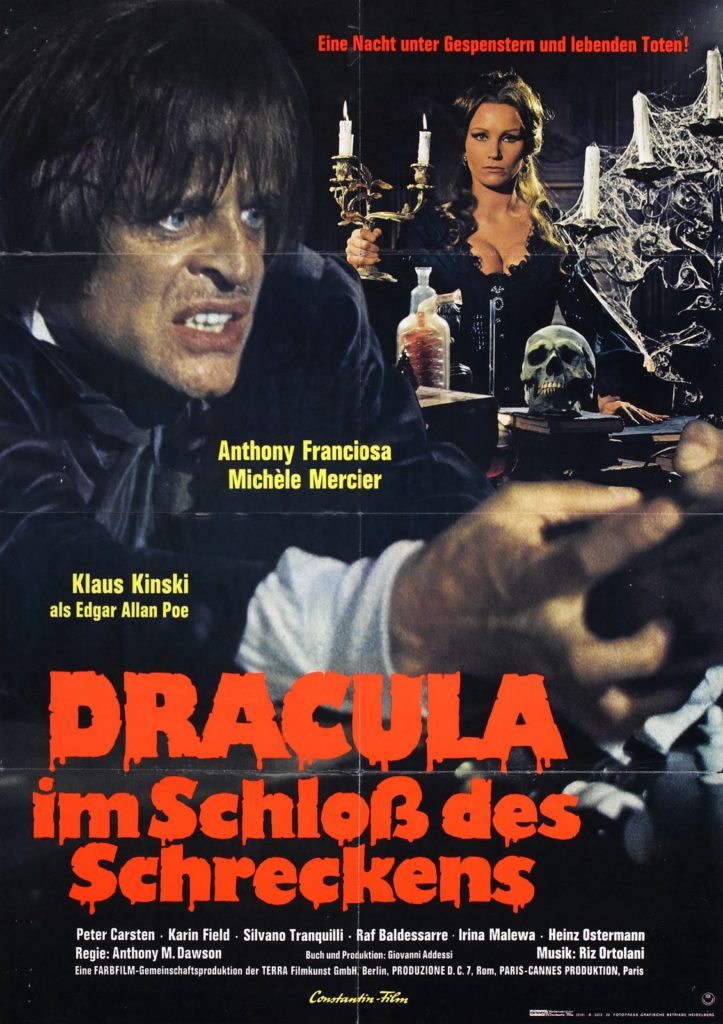

Dir: Antonio Margheriti

Star: Anthony Franciosa, Michèle Mercier, Peter Carsten, Klaus Kinski

For one of Kinski’s cameo roles – his appearances strictly book-end the film, this is actually not bad, an Italian Gothic horror set in the 1830’s. It’s a remake of an earlier film, 1964’s Castle of Blood, also directed by Margheriti (mostly – let’s not get into that here!), but which flopped at the box-office. The director believe this was due to it being in black-and-white, so decided to remake it in color. He appeared to regret this, calling the decision”stupid.” I haven’t seen the original, so can’t comment, but found this to be an effective enough tale, good enough to leave me interested in locating a decent print. For the one I watched was badly washed-out, pan-and-scanned (with a lot of scanning!), edited down by about 20 minutes, and dubbed into English with Greek subtitles. That it still retained my interest, thus says a good deal.

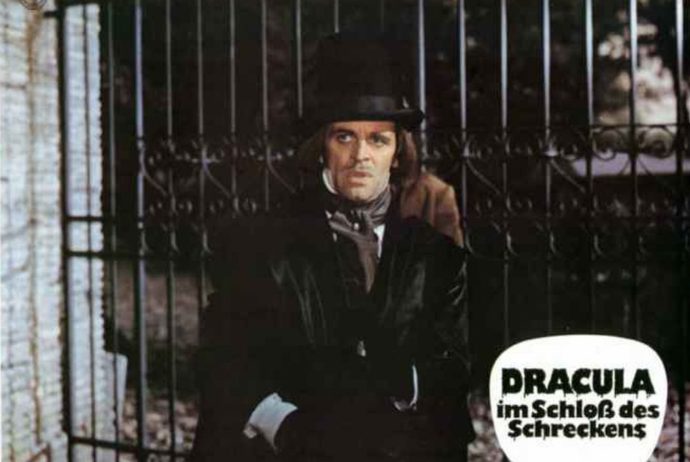

The wraparound story is a good one, and sees writer Edgar Allen Poe (Kinski) visiting England – there’s no indication, incidentally, this trip ever took place [Though Poe did spent several years in London, it was as a young boy]. It starts with Poe, Lord Blackwood and writer Alan Foster (Franciosa) drinking together in a pub, where Poe reveals that his stories aren’t works of fiction, but reports of events that actually happened, and were witnessed by him. The skeptical Foster scoffs at this, but Blackwood agrees with Poe that there are more things in heaven and earth, etc., and wagers ten pounds with Foster that he will be unable to spend an entire night in a haunted, empty castle owned by the nobleman. The writer is dropped off at the (impressively spiky) castle gates by Poe and Blackwood, and goes inside for a lengthy sequence of Foster walking the halls and rooms of the deserted manor.

Except, naturally, it turns out to be far from deserted, playing home to a wide spectrum of characters – some of whom happen to bear a strong resemblance to portraits hanging on the walls. The first of these to appear is Elisabeth Blackwood (Mercier), for whom Foster falls, and falls hard; this is used to explain his reluctance to leave, once the escalating weirdness achieves full effect. She’s followed shortly after by another, rather more sullen beauty, Julia (Karin Field), and before you know it, this supposedly vacant home is playing host to an entire ball. Turns out, as you have perhaps guessed already, that these are not living people, but spectral entities left over from previous tragic events.

Except, naturally, it turns out to be far from deserted, playing home to a wide spectrum of characters – some of whom happen to bear a strong resemblance to portraits hanging on the walls. The first of these to appear is Elisabeth Blackwood (Mercier), for whom Foster falls, and falls hard; this is used to explain his reluctance to leave, once the escalating weirdness achieves full effect. She’s followed shortly after by another, rather more sullen beauty, Julia (Karin Field), and before you know it, this supposedly vacant home is playing host to an entire ball. Turns out, as you have perhaps guessed already, that these are not living people, but spectral entities left over from previous tragic events.

This is explained to Foster by Dr. Carmus, an occult scholar who went to the castle to carry out some research, only to be trapped there himself. The same fate seems likely to befall Foster – except for the love that he and Elisabeth share, leading to her trying to help him escape the grounds before dawn, when he is doomed to join the other spirits, forever. At least, that appears to be the plot here: I was somewhat surprised to read other synopses saying things like, “Near the end of the film, the ghosts reveal their true nature: they aren’t actually ghosts but vampires with ghostly powers, and they need Foster’s blood in order to maintain their existence,” because that particular angle would appear to be part of the 20 minutes missing from the version I saw. This would at least somewhat explain the German title, Dracula im Schloß des Schreckens (“Dracula in the Castle of Secrets”), even if Dracula is notable by his complete absence.

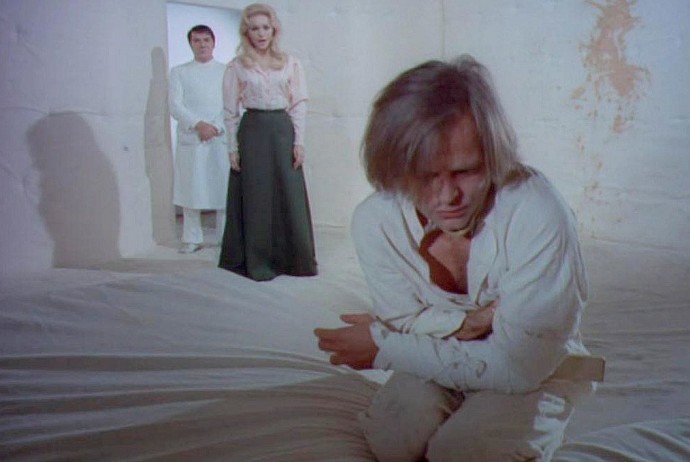

While enjoyable enough, with no shortage of atmosphere to be found, I suspect Mercier is likely a downgrade from the phenomenal Barbara Steele, who played the same role in Castle: here, she’s pretty, and not much more, hardly coming over as the sort of woman to inspire the level of devotion shown by Foster. Given its era, this also feels tame; things had moved on significantly in the horror world since the original film, and some more sex and violence probably wouldn’t have gone amiss. It is a bit of a shame the early direction isn’t sustained. I love the concept of Poe’s stories actually being journalism, and think it would have been a fantastic idea to have had an entire series of films based on that premise [H.P. Lovecraft immediately comes to mind as another author for whom this would work]. There’s a sequence which plays under the opening credits that shows where this idea could have gone: Poe stalking his way through a graveyard, all disheveled and flailing, looking for a specific grave and digging it up, before it cuts to the pub where he is telling the story to Blackwood and Foster – still, all disheveled and flailing.

Kinski as Poe is an inspired bit of casting; if I can’t say how accurate the portrayal of Poe as a twitchy, sweaty laudanum addict type might be, I can’t deny how much fun it is to watch. Undeniably, it’s a vast improvement over Klaus’s other cameo as a “great author”, playing the Marquis De Sade in Justine, where he got to do very little except sit in a cell and pretend to scribble furiously. Margheriti had worked with Kinski before to great effect, in And God Said To Cain, and it’s just a shame that his screen time here is limited to a handful of scenes. While the rest is more undeniably more entertaining than some of the Kinski cameos I’ve had to endure in the course of putting this site together, the gap between Klaus and the rest of the cast is rather apparent. I’d have willingly ponied up ten quid, for everyone to just sit in the pub and listen to some more of Poe’s stories, rather than go out on a cold night to a freezing and unwelcoming pile of stones – ectoplasmic babes or no ectoplasmic babes…

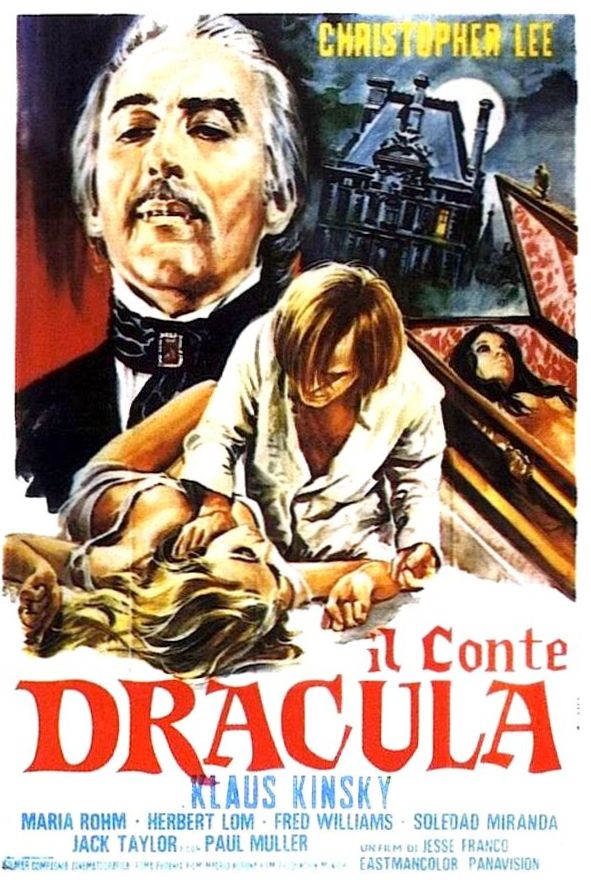

There’s good reason for this, because the film had as many as six different directors at various stages of proceedings.

There’s good reason for this, because the film had as many as six different directors at various stages of proceedings.

It is, very much, a loving homage to F.W. Murnau’s original, though the expiration of copyright allows Herzog to use the actual names of the characters, rather than, as Murnau did, make them up in a (failed) attempt to avoid a lawsuit. The make-up is almost identical, not just on the vampire, but on Lucy Harker (Adjani), who has the same pasty-pale pancake on her face and perpetually-concerned expression as Ellen Hutter in the original – see the illustration on the left. Indeed, sometimes the only way to tell her and Dracula apart is to look for the pointy teeth.

It is, very much, a loving homage to F.W. Murnau’s original, though the expiration of copyright allows Herzog to use the actual names of the characters, rather than, as Murnau did, make them up in a (failed) attempt to avoid a lawsuit. The make-up is almost identical, not just on the vampire, but on Lucy Harker (Adjani), who has the same pasty-pale pancake on her face and perpetually-concerned expression as Ellen Hutter in the original – see the illustration on the left. Indeed, sometimes the only way to tell her and Dracula apart is to look for the pointy teeth.