Dir: Antonio Margheriti

Star: Lewis Collins, Cristina Donadio, Manfred Lehmann, Klaus Kinski

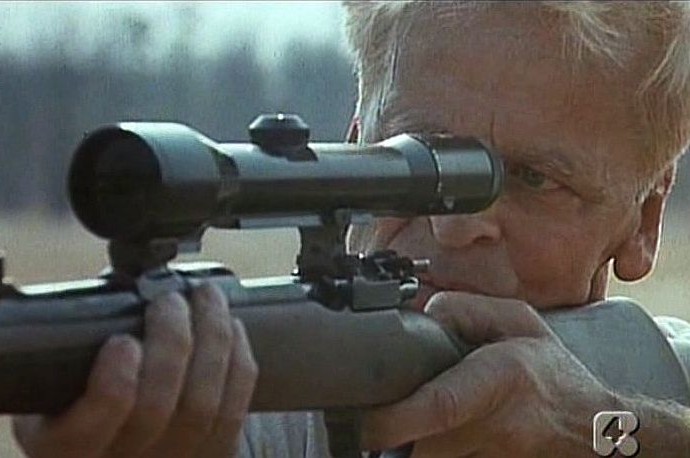

Part of my childhood growing up in the late seventies was The Professionals, a two-fisted TV series centered around Bodie and Doyle, operatives of fictional British government agency, C.I.5, and their boss Cowley. While my memories are vague, I recall a lot of whizzing around, in what Wikipedia helpfully tells me was a Ford Capri, with a lot of shootouts and punch-ups. Like most 12-year-old boys at the time, I wanted to be Bodie. Or Doyle. I forget which. I mention this, because Bodie was played by Collins, and watching him running around the Philippino jungles, pretending it’s somewhere in “Latin America” was an immediate throwback to watching him running around the streets of North London.

This was the second of three movies he made with Margheriti, following Code Name: Wild Geese (an unofficial sequel to The Wild Geese) the previous year, which also had Kinski in a supporting role. It begins with a tense attack by Enrique Carrasco (Collins – yeah, not exactly an obvious Hispanic) and his allies on a dam, seeking to disrupt the fuel distribution network of President Homoza, the man who rules over this unnamed Latin American country with an iron fist. When the plan succeeds, Homoza orders the head of his secret police, Silveira (Kinski), to capture the “terrorists” responsible – or failing that, render the local population into such a state of fear, that Carrasco will be unable to rely on them for support.

Thus begins a game of cat and mouse between Silveira and Carrasco, who joins forces with the typical slew of characters you get in movies like this – a foreign mercenary, a Catholic priest (Lehmann), hot local chick Maria (Donadi). Meanwhile, Silveira and his militia forces stop at nothing to paint Carrasco and crew as the bad guys, including gunning down refugees, shooting up a hospital, and even blowing up a plane full of 185 kids and blaming it on the rebels. Damn: even by the standards of psychopathy we’ve come to expect from our #1 German lunatic, that’s cold. Needless to say, this doesn’t stop the revolutionaries from their mission, and the tide begins to turn as they blow up a freight train – and the oil refinery through which it is going at the time. Inevitably, in ends with Silveria making the fatal mistake of entering the field himself, a decision which leads to him being Qadaffi’d by the locals before Carrasco can intervene.

Thus begins a game of cat and mouse between Silveira and Carrasco, who joins forces with the typical slew of characters you get in movies like this – a foreign mercenary, a Catholic priest (Lehmann), hot local chick Maria (Donadi). Meanwhile, Silveira and his militia forces stop at nothing to paint Carrasco and crew as the bad guys, including gunning down refugees, shooting up a hospital, and even blowing up a plane full of 185 kids and blaming it on the rebels. Damn: even by the standards of psychopathy we’ve come to expect from our #1 German lunatic, that’s cold. Needless to say, this doesn’t stop the revolutionaries from their mission, and the tide begins to turn as they blow up a freight train – and the oil refinery through which it is going at the time. Inevitably, in ends with Silveria making the fatal mistake of entering the field himself, a decision which leads to him being Qadaffi’d by the locals before Carrasco can intervene.

There’s more than a slight degree of irony in producer Erwin C. Dietrich opting to use the Philippines as a stand-in for a despotic banana republic – because the country was, at the time, hardly any different, being in its third decade of control by President Ferdinand Marcos, hardly a model leader. This was made not very long after opposition leader Benigno Aquino had been gunned down at Manila Airport, getting off the plane bringing him back from exile. And barely four months after Kommando opened in Germany, Marcos and his wife Imelda were booted from office and bailed out on the country entirely, famously leaving behind her collection of 2,700 pairs of shoes. So, safe to say, knowledge of the contemporary and future political climate adds a certain resonance to things.

That said, there’s good reason the country was a hotbed of B-movie film production around this time: you certainly got lots of value for your money (I vaguely recall reading that, if you got on Marcos’s good side, he’d loan you military hardware and troops for your shoot). The budget here was reportedly about 15 million Swiss francs – the most expensive Swiss-financed production to that point – which translates to about $16.5 million in today’s money, so this wasn’t a bargain basement piece of work. About half of that went on effects, and it’s all up on the screen, with some pretty impressive model work being blown up, in particular the opening dam and the oil refinery. Though perhaps the coolest things ever, for any wannabe evil overlord, are the helicopter gunships with flamethrowers mounted in their noses. There’s one shot of it letting rip, right into the camera lens, which had me wondering if this was shot in 3D.

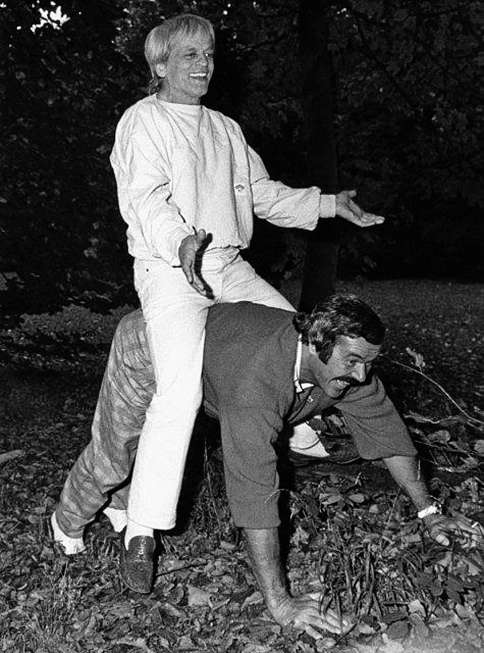

During the early stages, which have Collins roaming the jungle, while Kinski sits comfortably in the President’s palace, I wondered if this had been part of the contract negotiations, but as mentioned, Klaus does end up getting down and dirty as well. Though going by the (low-resolution, sorry) clip below, it doesn’t appear to have done anything at all for his sunny disposition! The distance between hero and antagonist does impact things: it feels more dispassionate, almost like a chess match, watching them move their forces around the board, though Carrasco is in the trenches with his troops, to a much greater degree. It is a good role for Kinski, and he makes the most of it; however, the focus is very much on the good guys, and Collins (who once auditioned for Cubby Broccoli as a possible James Bond) doesn’t do much to stand out from the foliage.