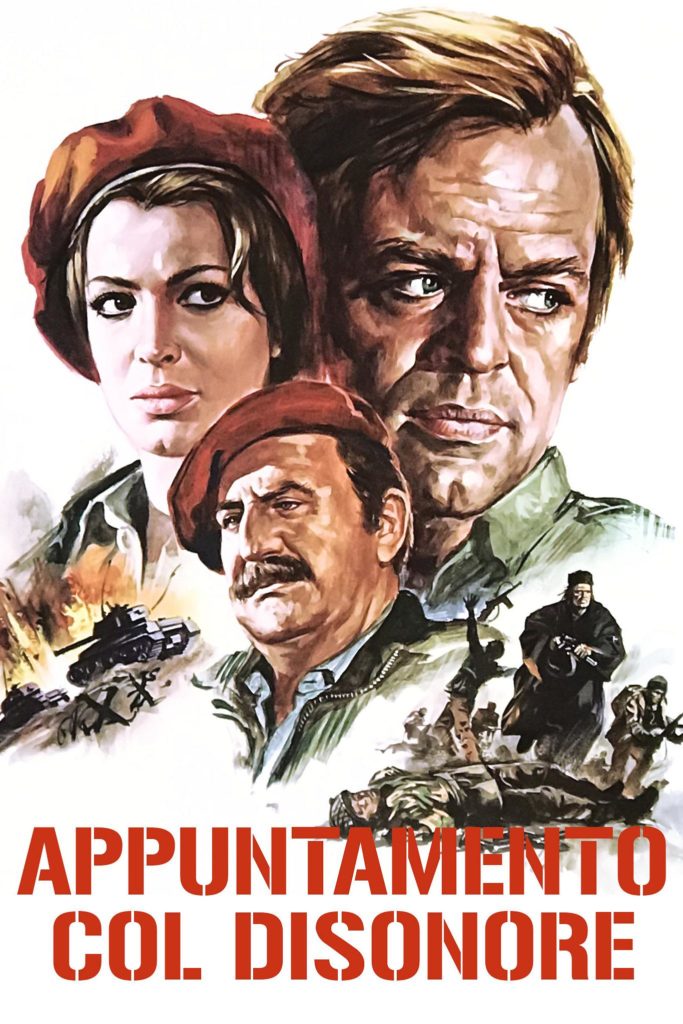

Dir: Rudolf Zehetgruber

Star: Adrian Hoven, Ann Smyrner, Peter Vogel, Klaus Kinski

a.k.a Die Schwarze Kobra

This was a real struggle to get through. As in, within about five minutes, I found myself idly staring at my phone instead of the screen. Okay, let’s rewind and start again. This time, I made it almost ten minutes in before getting bored and drifted away. Rewind. Third time’s the charm, right? Well, I did get to the end. But I would have to admit, that had I been quizzed about the film’s content, I would have been unable to answer in more than the broadest details. So, here we are, making attempt #4, with the film playing on my second monitor as I write this. Is it that “bad” a movie? No, probably not. It is, however, almost entirely unremarkable, the presence of Klaus Kinski – specifically, a “with Klaus Kinski” movie – being its sole redeeming feature.

It begins with the hijacking of a truck being driven by Peter Karner (Hoven). It’s executed b thugs operating on the instructions of the mysterious, sword-stick wielding “Mr. Green”, who believe there are narcotics hidden in its cargo. They shoot Peter’s Corsican co-driver, Martinez Manuzzo, which is unfortunate, since he’s the one who actually knows about the drugs. They’re initially unable to pry any information from the driver, and Peter is able to escape. He hides out at a road-house owned by his girlfriend, Alexa Bergmann (Smyrner), while the truck and Manuzzo’s corpse come to the attention of the cops. This means that the authorities and both sets of criminals – Green’s and Manuzzo’s – are now on his trail. The former think he was responsible for the death of Manuzzo, though newly-appointed Kriminalassessor Dr. Alois Dralle (Vogel) has his doubts; the latter still want to retrieve the drugs.

This is mostly Hoven’s movie, as his hero tries to solve the case on his own, either bravely or stupidly walking right into the club out of which Mr. Green’s gang operates. He’s rescued only thanks to the convenient arrival of Manuzzo’s wife, Paola, and her henchmen. She at least runs her criminal endeavors out of a novel cover – a recording studio. This is where we first meet Kinski’s character, a coke-addicted pianist called Charly. He overhears Paola negotiating with the Green gang, and goes behind her back to them, offers to trade Peter’s location for drugs. The resulting visit is where the titular cobra shows up, being part of a roadside zoo which sits next to Alexa’s establishment. It slithers away, only to be fought by a conveniently passing mongoose, which I did not realize was native to central Europe. Actually, it’s just an excuse for some stock footage of a mongoose/snake fight, which seems to have strayed in from a mondo movie.

The film eventually ends up chasing its own tale (sic), in a slew of murders, betrayals and kidnapping, with Alexa being abducted by Mr. Green, in order to force Peter to show up at the club. He does, and a reasonably impressive bar-brawl breaks out, with copious property damage, as Peter and his large ally, the roadsize zoo owner Punkti (Ady Berber), rush to the rescue. Only, Alexa has already been whisked away to another location. This is where the film’s plot collapses entirely under its own weight, with four separate groups of people – two gangs, the police and Peter’s – whizzing around. It feels like you need some kind of diagram, involving a whiteboard and copious amounts of red string, to keep track of who is doing what to whom, where and why.

Punkti gets to brawl with someone even larger and uglier than himself, and it all ends at the junkyard owned by Stanislas Raskin, Green’s #2. There’s a fairly grisly, if not explicitly depicted end for someone there: although this is utterly contrived and implausible, it does lead to a rare moment of black humor before the credits roll. Once more my attention, which had already been wavering for a while, truly struggled to get across the finishing line. There aren’t many movies I have to start watching from the beginning four separate times to get to the end. To be honest, if this had not been part of Project Kinski, I sincerely doubt I would have bothered more than once.

Hoven was a long-term actor, who got into producing and directing later in his career: he’s probably best-known for the Mark of the Devil franchise, though in 1974’s Dandelions, also directed Rutger Hauer early in the Dutch actor’s career. Like Hoven, this movie is Austrian rather than German: it seems to be trying to ape the look and feel of the Rialto krimis, not least by bringing Kinski and others, such as the hulking Berber, in for guest appearances. The end result is just unsatisfying, like a wax model of a chocolate cake, compared to the real thing. It may not have helped that I wasn’t able to locate a subtitled version, and had to go with an English dubbed one. However, the voice they used for Kinski does at least seem in approximately the same timbre as the actual actor. This can’t help the script though, which never manages to rise above the pedestrian.

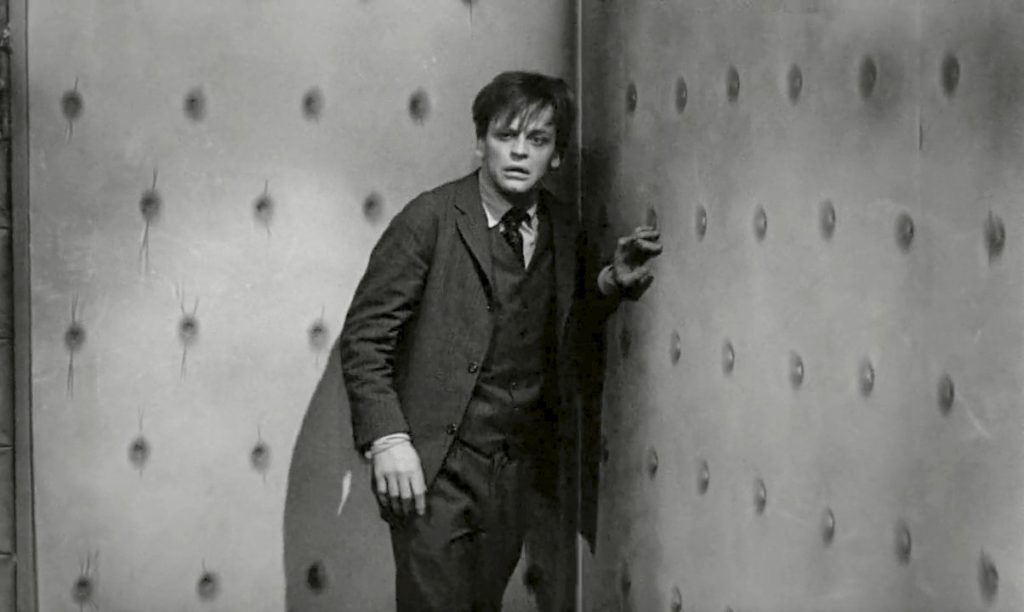

I did still like Kinski’s performance, which is as loose as Charly’s dangling necktie, at times functioning closer to a belt. It probably offers the only element in the entire film that will stick in the memory. Even by his standards, it’s a remarkably twitchy performance, with Charly alternating between slimily ingratiating (when he needs a fix) and flat-out creepy (when he’s in possession of his cocaine). His eyes never seem to look in the same direction for two consecutive shots, on occasion (as shown at the top), appearing to break the fourth wall and stare directly into the camera. This isn’t something commonly seen in mainstream sixties thrillers. Having committed one too many betrayals in the cause of his habit, Charly comes to an ignominious end, naturally, meeting the pointy end of Mr. Green’s sword-cane in a secret room at his club. My interest in the movie died alongside him, with twenty minutes still to go.