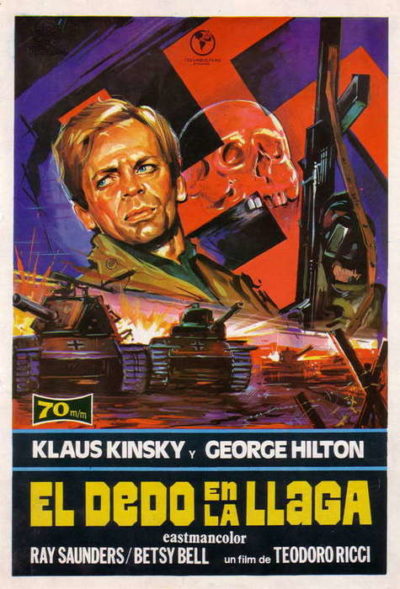

Dir: Tonino Ricci

Star: George Hilton, Klaus Kinski, Ray Saunders, Betsy Bell

a.k.a. Salt in the Wound

It’s a bit odd how the Italian film industry in the early seventies were quite the war machine, churning out film after film about WW2. After all, it was less than 30 years since they had, let’s not forget, been on the losing side, thanks to Mussolini’s alliance with Hitler. I guess enough time had passed for a movie-going generation to arise, who hadn’t been through the war, and so weren’t averse to reliving it. A bit like the sudden burst of Hollywood films in the eighties about Vietnam – a conflict that didn’t exactly end well for the US of A, Rambo notwithstanding. Though here, there’s a little historical revisionism at work: even though it firmly takes place in Italy, it’s very much America vs. Germany, with the locals simply the residents of occupied territory, who welcome the Yanks as liberators. Not sure how entirely true that was; I’ll defer to historical experts.

The other aspect that’s particularly unusual here is Kinski’s role. While neither his first nor his last war movie, it’s the only one to this point I’ve seen where he plays an American, rather than a Naxi as you’d expect. Admittedly, he’s not exactly a heroic GI. Indeed, the opening scene sees Corporal Norman Carr (Kinski) engaging in a spot of murder and looting, not exactly authorized by the articles of war. He’s captured by Allied military police, and hauled up before a military tribunal along with another soldier, Private Calvin Mallory (Saunders). Both are found guilty and sentenced to face a firing squad the next morning. In charge of the squad who’ll be executing the execution, as it were, is Lieutenant Michael Sheppard (Hilton), fresh out of West Point, and who rigorous approach to doing things by the book, is the subject of some bleak amusement for his superiors, who have first-hand experience of the gulf between that and the realities of war.

Carr and Mallory are literally up against the wall, when fate intervenes, in the shape of an ambush by German troops. The prisoners seize the chance to escape, and Sheppard, the only survivor of his squad goes with them. He’s quite open about the fact that he’s going to bring them back and make them face justice, and I have to say, Carr is remarkably chill about the prospect. [Mallory, meanwhile, is remarkably chill about virtually everything. He spent the night before his scheduled execution singing hymns, right up until his cellmate had had enough] After successfully ambushing a group of Nazi soldiers, they acquire a jeep, with the aim, expressed by Carr, of keeping as far away from actual fighting as possible. This takes them to the town of San Michele, which initially appears deserted. Except, the inhabitants have actually been in hiding. They suddenly pour out to greet what they believe to be the forces of liberation, rather than two war criminals and an officer with a stick up his ass.

Carr and Mallory are literally up against the wall, when fate intervenes, in the shape of an ambush by German troops. The prisoners seize the chance to escape, and Sheppard, the only survivor of his squad goes with them. He’s quite open about the fact that he’s going to bring them back and make them face justice, and I have to say, Carr is remarkably chill about the prospect. [Mallory, meanwhile, is remarkably chill about virtually everything. He spent the night before his scheduled execution singing hymns, right up until his cellmate had had enough] After successfully ambushing a group of Nazi soldiers, they acquire a jeep, with the aim, expressed by Carr, of keeping as far away from actual fighting as possible. This takes them to the town of San Michele, which initially appears deserted. Except, the inhabitants have actually been in hiding. They suddenly pour out to greet what they believe to be the forces of liberation, rather than two war criminals and an officer with a stick up his ass.

Naturally, our trio aren’t averse to being treated like heroes. Carr hits it off with local beauty Daniela (Bell), and Mallory befriends a local kid: fatal mistakes, as we’ll see. However, Carr hasn’t entirely reformed, and when Sheppard sees him attempting to make off with the church’s treasures, it takes a bit of two-fisted encouragement to dissuade the perp. Further discussion on the topic is rudely interrupted, with the appearance of a brigade of Germans, intent on re-capturing the town, and we’re deep into Saving Private Ryan territory the rest of the way. The first wave of Axis attacks is successfully repelled, not least because they weren’t expecting much resistance. However, this only provides a brief respite, and it’s not long before the Nazis return, in greater force and this time bringing tanks with them. Can our heroes hold out until help arrives?

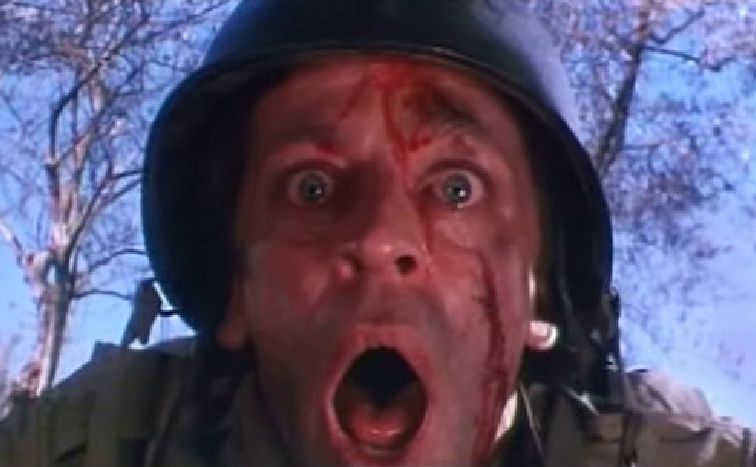

“My mother was a whore.” So begins one of Kinski’s monologues, as he explains his cynicism to Daniela. It has to be said, he makes a compelling case, for example, pointing out the Germans have “God is with us” inscribed on their belt-buckles: everyone thinks that. I don’t want to spoil anything, but let’s just say the chances for either him or Mallory making it to the end, are severely hampered by the fact that their respective pals have all the survival skills of suicidal lemmings. Daniela, for example, rushes in to cling on to Carr’s arm, shrieking “I just want to be with you!” It doesn’t end well for her. It also leads to a point-of-view shot from inside one of the German tanks, where we get to see Klaus making the face shown at the end of the review. This must rank among the ten best Kinski faces of all time, and it probably the last thing I would want to see coming at me, even if safely embedded inside a tank.

The pacing is a bit off, in that the middle contains rather more sitting around an Italian village and chatting, than I would have said is strictly necessary. However, after a tendency for the early battles to be little more than schoolyard level spraying of automatic gunfire, the final confrontation is extremely well-staged and gives as good an insight into the terror of facing armored opposition as anything I’ve seen, the tanks being depicted basically as unstoppable. When that turret starts to swivel in your direction… you’d better get out of the way. Kinski’s character here is a fascinating one too. He’s clearly no saint, and has more baggage than an entire airport terminal, yet you sense he’s a product of circumstance rather than inherent malice. Carr has clearly thought about his situation, and decided it’s untenable, leading to him behaving on the purely selfish level. As such, it represents the other end from Ryan‘s heroic altruism, and is likely all the better for it. For my money, this is the best of the Kinski war films I have seen so far.

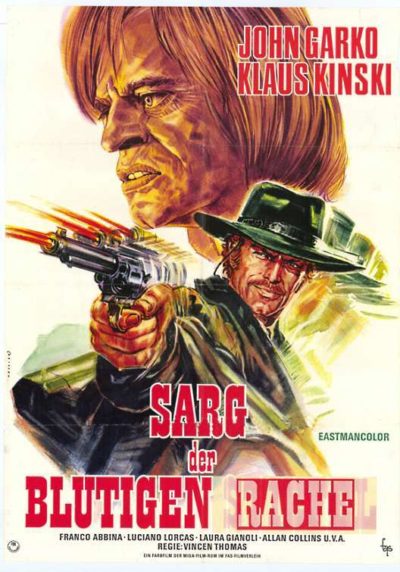

This moral ambivalence is typical of the spaghetti Western, where it’s less black hats vs. white hats, than various shades of muddy grey facing off. Here, we have not-so-good guys pretending butter wouldn’t melt in their mouth, as well as a guy who is being framed and sent to the gallows, because of anti-social tendencies – yet, as the ending shows, Chester may not be entirely innocent either. Curiously, this was the second film I’ve seen, in relatively short order, where Kinski plays a man convicted of a murder he didn’t commit, following on from June’s

This moral ambivalence is typical of the spaghetti Western, where it’s less black hats vs. white hats, than various shades of muddy grey facing off. Here, we have not-so-good guys pretending butter wouldn’t melt in their mouth, as well as a guy who is being framed and sent to the gallows, because of anti-social tendencies – yet, as the ending shows, Chester may not be entirely innocent either. Curiously, this was the second film I’ve seen, in relatively short order, where Kinski plays a man convicted of a murder he didn’t commit, following on from June’s

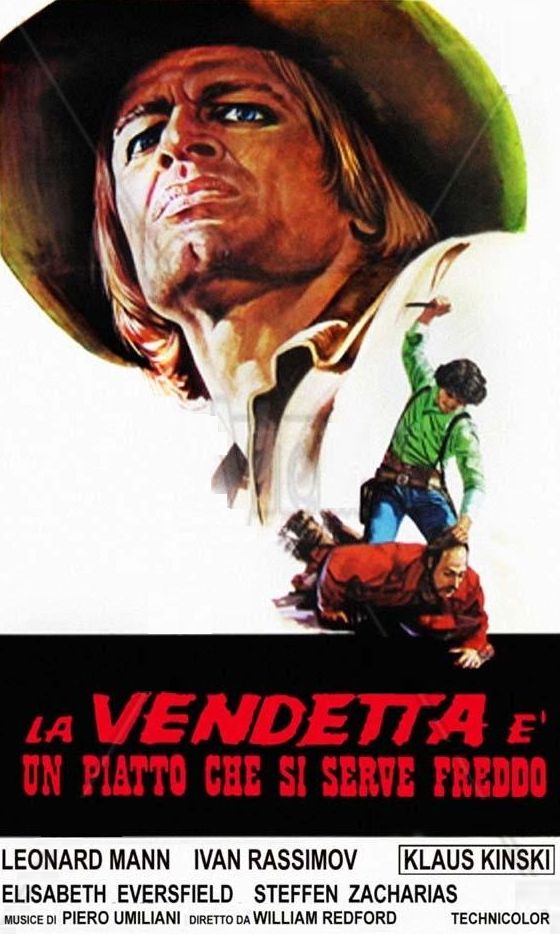

Jeremiah heads off Boone and his men on their way to carry out the attack, frees the tribesmen whose corpses are intended to be left at the scene, and heads back to infiltrate his way into Perkins inner circle. For this is where the Italian title comes into play: it translates as “Revenge is a dish best served cold.” And there I was, thinking all the time it was a Klingon proverb. Quentin Tarantino was lying to me! [And it’s not as if a film geek like QT, especially one so devoted a fan of spaghetti Westerns, would be unaware of this one, though the phrase pre-dates the movie, obviously] So, ten years on, it’s time for those who were really behind the murder of our hero’s family, to pay for their crimes.

Jeremiah heads off Boone and his men on their way to carry out the attack, frees the tribesmen whose corpses are intended to be left at the scene, and heads back to infiltrate his way into Perkins inner circle. For this is where the Italian title comes into play: it translates as “Revenge is a dish best served cold.” And there I was, thinking all the time it was a Klingon proverb. Quentin Tarantino was lying to me! [And it’s not as if a film geek like QT, especially one so devoted a fan of spaghetti Westerns, would be unaware of this one, though the phrase pre-dates the movie, obviously] So, ten years on, it’s time for those who were really behind the murder of our hero’s family, to pay for their crimes.

I guess, in 1967, this was edgy stuff. Anyway, back in the impenetrable morass which is the plot, you’d better hold on with both hands, especially in the final 10 minutes when Craig pulls the solution out, with a flourish befitting a cabaret magician finding a rabbit in his top-hat, and about as much logic. Yes, I suppose the culprit could have committed the crimes as Craig alleges; but if I was their defense attorney, I’d be filing for a motion to dismiss based on a severe lack of evidence. It could have been just about anybody. My money’s on Mangrove, mostly because I tend to be suspicious of psychiatrists whose office has a painting, behind which is a hidden snake-cage, the inhabitant of which he uses, for example, to traumatize a nurse who has found out about his nefarious schemes.

I guess, in 1967, this was edgy stuff. Anyway, back in the impenetrable morass which is the plot, you’d better hold on with both hands, especially in the final 10 minutes when Craig pulls the solution out, with a flourish befitting a cabaret magician finding a rabbit in his top-hat, and about as much logic. Yes, I suppose the culprit could have committed the crimes as Craig alleges; but if I was their defense attorney, I’d be filing for a motion to dismiss based on a severe lack of evidence. It could have been just about anybody. My money’s on Mangrove, mostly because I tend to be suspicious of psychiatrists whose office has a painting, behind which is a hidden snake-cage, the inhabitant of which he uses, for example, to traumatize a nurse who has found out about his nefarious schemes.

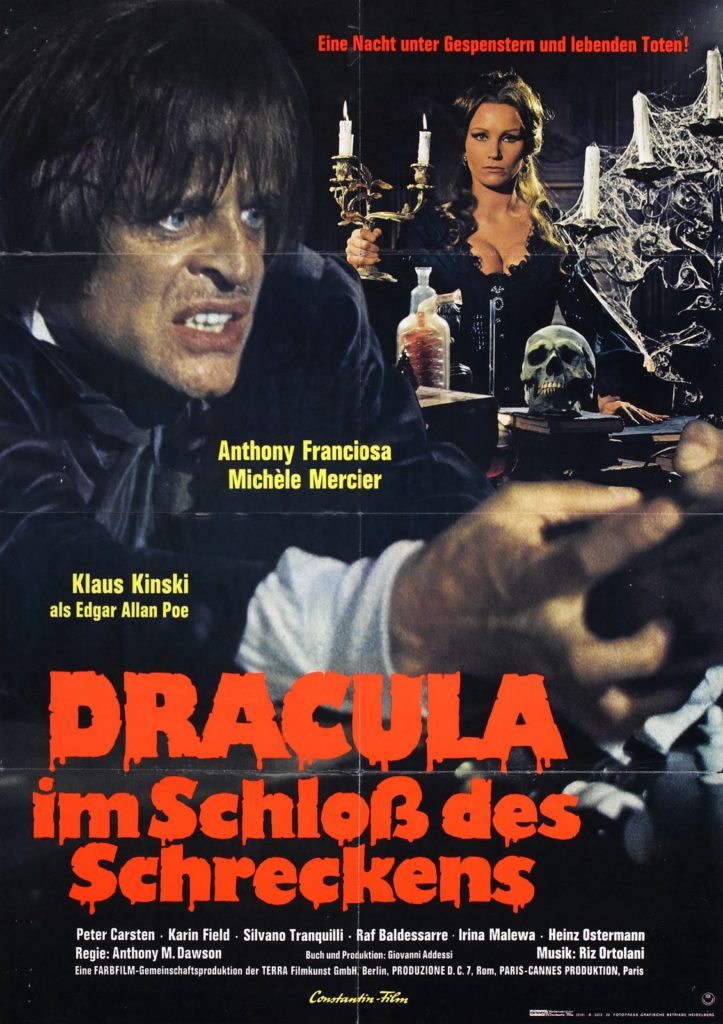

Except, naturally, it turns out to be far from deserted, playing home to a wide spectrum of characters – some of whom happen to bear a strong resemblance to portraits hanging on the walls. The first of these to appear is Elisabeth Blackwood (Mercier), for whom Foster falls, and falls hard; this is used to explain his reluctance to leave, once the escalating weirdness achieves full effect. She’s followed shortly after by another, rather more sullen beauty, Julia (Karin Field), and before you know it, this supposedly vacant home is playing host to an entire ball. Turns out, as you have perhaps guessed already, that these are not living people, but spectral entities left over from previous tragic events.

Except, naturally, it turns out to be far from deserted, playing home to a wide spectrum of characters – some of whom happen to bear a strong resemblance to portraits hanging on the walls. The first of these to appear is Elisabeth Blackwood (Mercier), for whom Foster falls, and falls hard; this is used to explain his reluctance to leave, once the escalating weirdness achieves full effect. She’s followed shortly after by another, rather more sullen beauty, Julia (Karin Field), and before you know it, this supposedly vacant home is playing host to an entire ball. Turns out, as you have perhaps guessed already, that these are not living people, but spectral entities left over from previous tragic events.

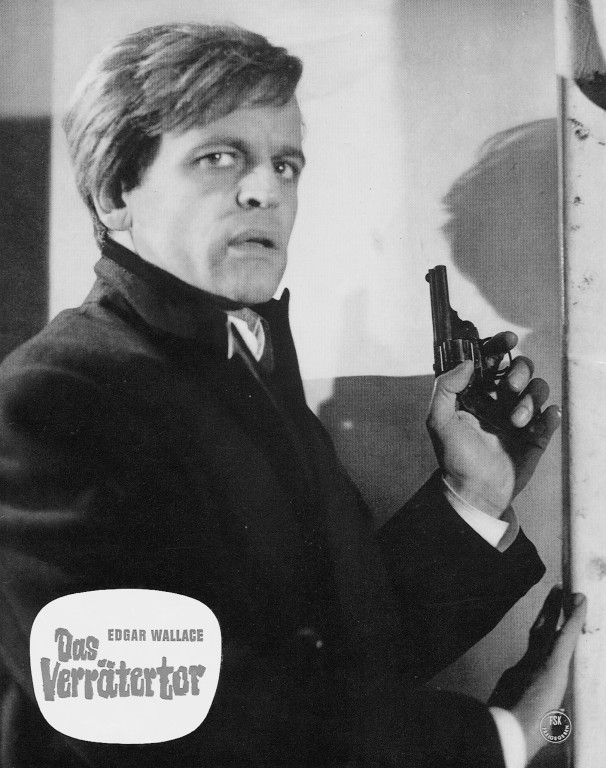

Bit of a surprise to see this is directed by Freddie Francis, an English film-maker, best known for his work as a cinematographer (winning Oscars almost three decades apart, for Sons and Lovers and Glory). As a director, in the sixties he was regularly employed by both Hammer and Amicus, helming Dracula Has Risen From the Grave, The Evil of Frankenstein and 1972’s Tales From the Crypt. Having once said, “Horror films have liked me more than I have liked horror films.” this movie is unusual, both in being German and a krimi, without any supernatural or horrific elements. The screenplay, similarly, was written by another Hammer horror veteran, Jimmy Sangster, based on Edgar Wallace’s

Bit of a surprise to see this is directed by Freddie Francis, an English film-maker, best known for his work as a cinematographer (winning Oscars almost three decades apart, for Sons and Lovers and Glory). As a director, in the sixties he was regularly employed by both Hammer and Amicus, helming Dracula Has Risen From the Grave, The Evil of Frankenstein and 1972’s Tales From the Crypt. Having once said, “Horror films have liked me more than I have liked horror films.” this movie is unusual, both in being German and a krimi, without any supernatural or horrific elements. The screenplay, similarly, was written by another Hammer horror veteran, Jimmy Sangster, based on Edgar Wallace’s

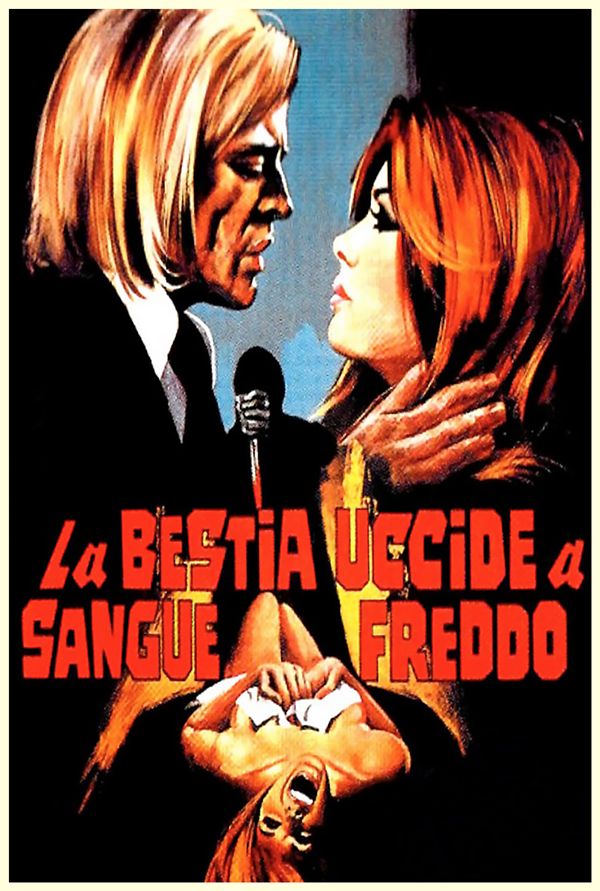

Anyone else, however, will likely find this irredeemably bad, to the point of unwatchable. I’ve seem some truly shitty examples of the giallo genre in my time, yet this one manages to scrape the bottom of the barrel, for its nonsensical plotting and feeble performances, lacking even the strong sense of visual style for which the field is generally renowned. Kinski is entirely wasted, with his doctor getting the absolute minimum of screen time, and the character could have been removed entirely without impacting the film to any significant degree. Di Leo clearly decided, “Why bother having Kinski, when you can have an apparently endless massage instead?” I suppose this choice could be considered as having some kind of artistic vision, except it’s a vision of which I want absolutely no part.

Anyone else, however, will likely find this irredeemably bad, to the point of unwatchable. I’ve seem some truly shitty examples of the giallo genre in my time, yet this one manages to scrape the bottom of the barrel, for its nonsensical plotting and feeble performances, lacking even the strong sense of visual style for which the field is generally renowned. Kinski is entirely wasted, with his doctor getting the absolute minimum of screen time, and the character could have been removed entirely without impacting the film to any significant degree. Di Leo clearly decided, “Why bother having Kinski, when you can have an apparently endless massage instead?” I suppose this choice could be considered as having some kind of artistic vision, except it’s a vision of which I want absolutely no part.

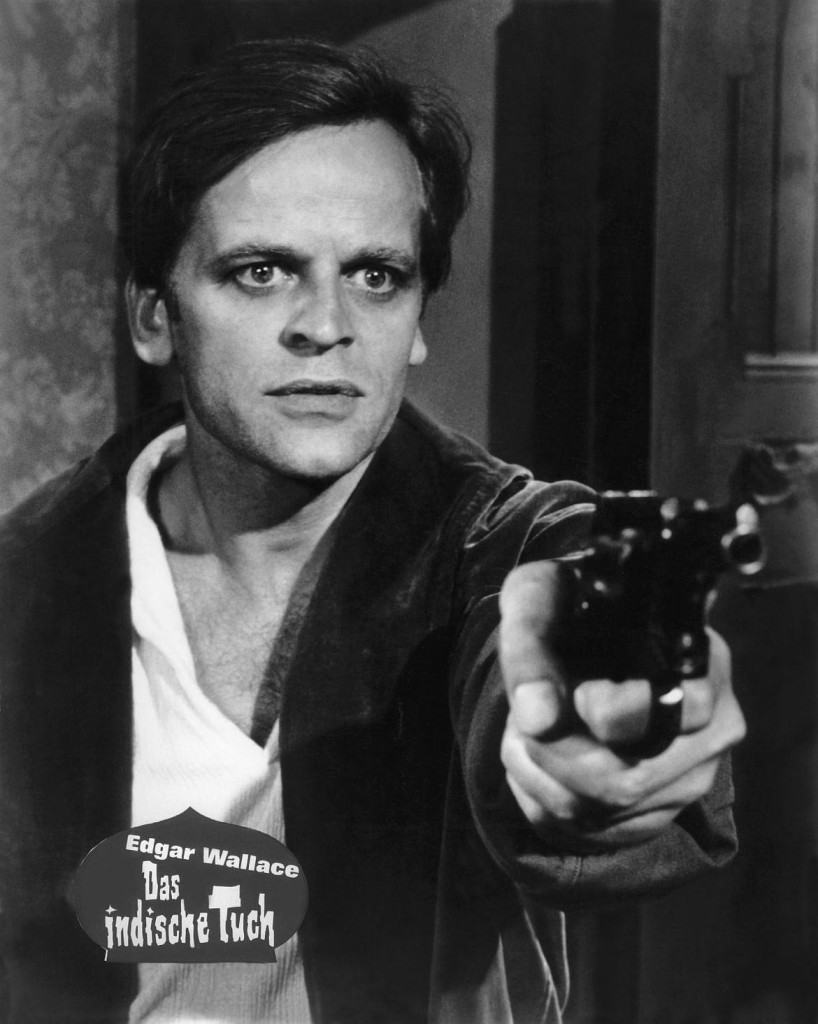

That said, I can’t say, I minded this self-aware attitude, which has probably stood the test of time better than a straight “mystery” approach would have, and largely inoculates the film against some of the more obvious criticisms that could be leveled at it. For example, it’s clearly an extremely cheap production, without a single exterior shot: the closest you get are some very obvious drawings of the manor seen from the outside, with smoke being blown across them. Taken seriously, these would be woeful indeed; instead, they set things up nicely, almost adding to the sense of meta-satire here. The characters here are similarly almost deliberately cliched, stereotypes of the field, running the gamut from the doting mother and her neurotically “gifted” son, all the way to… Klaus Kinski.

That said, I can’t say, I minded this self-aware attitude, which has probably stood the test of time better than a straight “mystery” approach would have, and largely inoculates the film against some of the more obvious criticisms that could be leveled at it. For example, it’s clearly an extremely cheap production, without a single exterior shot: the closest you get are some very obvious drawings of the manor seen from the outside, with smoke being blown across them. Taken seriously, these would be woeful indeed; instead, they set things up nicely, almost adding to the sense of meta-satire here. The characters here are similarly almost deliberately cliched, stereotypes of the field, running the gamut from the doting mother and her neurotically “gifted” son, all the way to… Klaus Kinski.

Thus begins a game of cat and mouse between Silveira and Carrasco, who joins forces with the typical slew of characters you get in movies like this – a foreign mercenary, a Catholic priest (Lehmann), hot local chick Maria (Donadi). Meanwhile, Silveira and his militia forces stop at nothing to paint Carrasco and crew as the bad guys, including gunning down refugees, shooting up a hospital, and even blowing up a plane full of 185 kids and blaming it on the rebels. Damn: even by the standards of psychopathy we’ve come to expect from our #1 German lunatic, that’s cold. Needless to say, this doesn’t stop the revolutionaries from their mission, and the tide begins to turn as they blow up a freight train – and the oil refinery through which it is going at the time. Inevitably, in ends with Silveria making the fatal mistake of entering the field himself, a decision which leads to him being Qadaffi’d by the locals before Carrasco can intervene.

Thus begins a game of cat and mouse between Silveira and Carrasco, who joins forces with the typical slew of characters you get in movies like this – a foreign mercenary, a Catholic priest (Lehmann), hot local chick Maria (Donadi). Meanwhile, Silveira and his militia forces stop at nothing to paint Carrasco and crew as the bad guys, including gunning down refugees, shooting up a hospital, and even blowing up a plane full of 185 kids and blaming it on the rebels. Damn: even by the standards of psychopathy we’ve come to expect from our #1 German lunatic, that’s cold. Needless to say, this doesn’t stop the revolutionaries from their mission, and the tide begins to turn as they blow up a freight train – and the oil refinery through which it is going at the time. Inevitably, in ends with Silveria making the fatal mistake of entering the field himself, a decision which leads to him being Qadaffi’d by the locals before Carrasco can intervene.

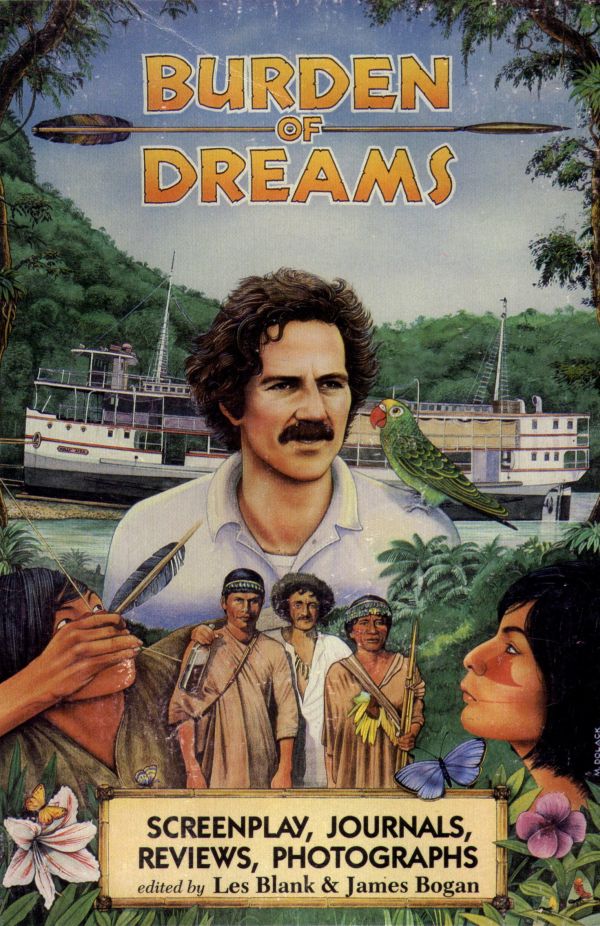

This is a project that was certainly cursed from the beginning, and there’s something appropriate about the film’s subject being a man attempting to do something ludicrous and borderline insane – drag a ship over a mountain – because Herzog’s persistence can only be admired. From the get-go, there were issues with the natives, and the initial location had to be abandoned, with locals burning the camp to the ground as the crew pulled out. Burden also includes footage from the original version, which started filming over a year later with new locations, and starred Jason Robards as Fitzcarraldo, with (of all people) Mick Jagger as his sidekick. After five weeks shooting, almost half the movie was already in the can, when Robards came down with amoebic dysentery and had to return to the United States, where his doctor forbade him from returning. While Herzog tried desperately to find another lead, Jagger had to return to his Rolling Stones related duties, and his character ended up being written out entirely.

This is a project that was certainly cursed from the beginning, and there’s something appropriate about the film’s subject being a man attempting to do something ludicrous and borderline insane – drag a ship over a mountain – because Herzog’s persistence can only be admired. From the get-go, there were issues with the natives, and the initial location had to be abandoned, with locals burning the camp to the ground as the crew pulled out. Burden also includes footage from the original version, which started filming over a year later with new locations, and starred Jason Robards as Fitzcarraldo, with (of all people) Mick Jagger as his sidekick. After five weeks shooting, almost half the movie was already in the can, when Robards came down with amoebic dysentery and had to return to the United States, where his doctor forbade him from returning. While Herzog tried desperately to find another lead, Jagger had to return to his Rolling Stones related duties, and his character ended up being written out entirely.