Dir: Steff Gruber

Star: Werner Herzog, Klaus Kinski, Steff Gruber, Peter Berling

We have quite a particular situation here. In this century we’ve had perhaps two or three people of Kinski’s calibre. There’s no-one else like him. He’s a wonder of the world. And this wonder can still be seen… There’s a duty, a great duty over me, since no-one else can do it. I have to be able to take it on. I want to be a good soldier of cinema.

Werner Herzog, to Steff Gruber

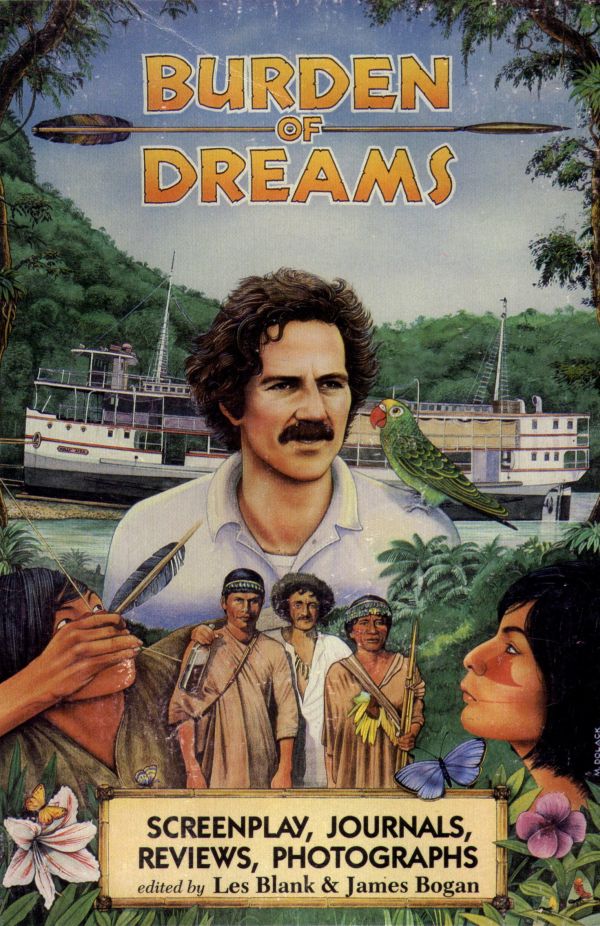

Documentaries involving Kinski are typically enthralling, simply because of the mercurial nature of the man. At any point, the volcano which is Klaus can potentially go off, delivering the kind of content which is gold to film-makers. But comparing this, about the making of Cobra Verde, to its most obvious sibling, Burden of Dreams, this certainly feels blander. While you still get the sense of how working with Kinski could be a challenge, the way it’s depicted here puts it in a different light. Rather than the sense of walking through a minefield, it is more of a grind – a test of Herzog’s stamina, rather than of his will. Klaus comes over almost as an energy vampire, someone with whom every interaction turns into a draining encounter, with minute details being questioned and every directorial decision being challenged.

From the start, it’s clear that Gruber is firmly on Herzog’s, saying of the director, “I admire his courage, which he constantly demonstrates in his films, how uncompromising he is, and his visionary power.” I guess it’s a good thing that the film admits its biases up front, though in general, I’m more a fan of documentaries that go wherever the story takes one, rather than where the makers come in with a predetermined agenda. Gruber sniffs daintily at the prospect of covering the juicier elements. While acknowledging that the arguments between director and star “dominate the shooting,” Gruber asks himself whether they should become the subject of the movie. He answers himself in the negative: “I resist the temptation. We’re not here to carry out gossip journalism.”

While he’s reluctant to do anything which might paint his hero in even a negative light, there are still scenes of the discussions – shot from a very long way away! “Why do I have to stand there?” demands Klaus, or “Why do I have a rifle?” Werner patiently explains his thinking, in the face of disparaging comments which would try the patience of most people. “I can’t shoot like this! I refuse to work with idiots!” goes Klaus, and continues to mutter darkly, even after the director has gone to take up his position. “What a load of rubbish! We shouldn’t shoot an important scene like this with two cameras!” It’s difficult to think of any other actor and director pairing which seemed to operate in such a state of perpetual tension.

Even Herzog has his breaking point. He tells Gruber, “There’s a final limit for me… When I reach it, then without hesitation, and within seconds, I’ll do things that nobody thinks are possible, and that will affect my life forever.” Though he never provides specifics, I immediately thought about the stories of him pulling a gun on Kinski. Compared to that, Cobra Verde seems to have been a cake-walk, Herzog adding, “I don’t think we’ll reach the limit here.” You do get a sense of why Herzog was prepared to tolerate it. He praises Kinski’s instincts: “He sees absolutely perfectly how physically people get frightened and run away. All at once something is there that has real life. When there’s no life in cinema you shouldn’t make it at all.”

What does come over is Herzog’s weariness of the entire process, but how he feels almost an obligation to make movies, despite the obvious pain the experience causes. “Making films isn’t a good job… You really shouldn’t do it too often.” There are moments where his frustration at the process comes through, such as when the local extras suddenly require double the previously-agreed daily rate, causing Werner to explode: “What you are demanding from me is nothing else but blackmail, and you should know that!” But he has little option except to give in to their demands. Gruber described the director as almost disassociating himself from proceedings: “Herzog acts as if he’s not involved, like a sleepwalker.”

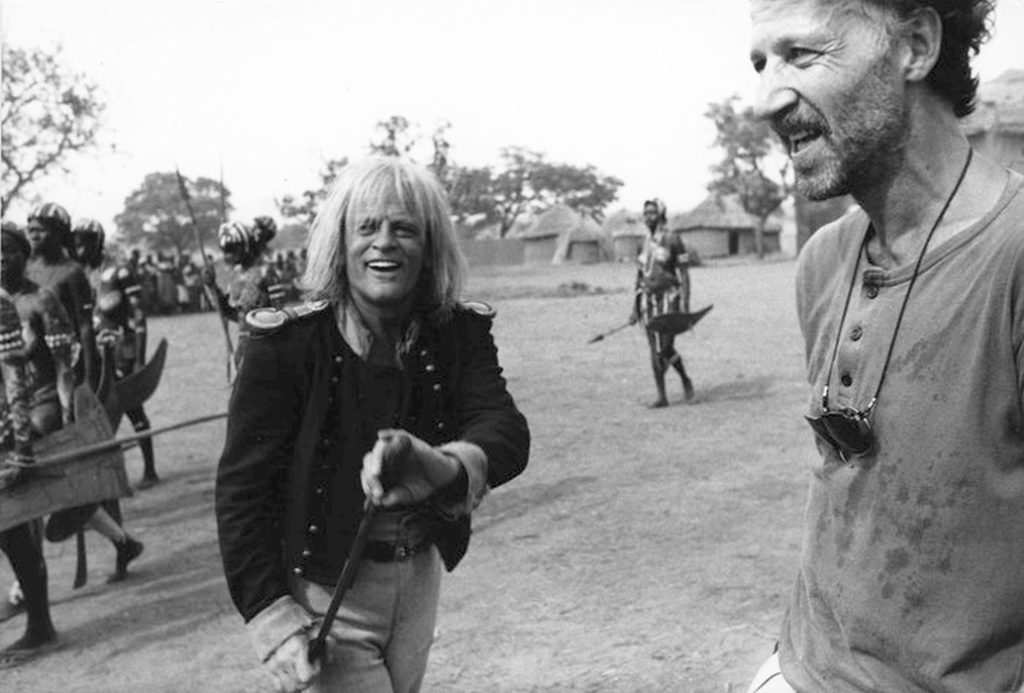

It is more about the film-making operation from the director’s perspective. Kinski, when he appears at all, is often a long way off. About the only extended scene where he’s is the focus sees him goofing off (top) with some of the extras who play his character’s Amazonian army. Though the line between goofing off and sexual harassment of these topless women is probably a complex equation involving time, place and intent. Gruber spends more time talking to the extras than Kinski (the latter being “none at all”), though this is sometimes quite interesting in its own terms. One said her boyfriend thought she was a prostitute, for showing her breasts to white men, and demanded she choose him or the film. She picked the film.

The week before watching this, I listened to the audio commentary for Apocalypse Now, which might be another example of what Gruber here calls “A sort of short-term colonialism.” There are definite parallels: an auteur director, shooting in a foreign country with a talented but problematic star, and often finding the process to be more of a chore than a pleasure. But they both also illustrate the magic of cinema, where what appears to be chaotic disorder can still result in the creator’s vision being realized, when all the elements come together. Watching this, you’ll wonder how Cobra Verde was ever finished, never mind that it provided an appropriate full-stop to the long, memorable sentence which were Herzog’s collaborations with Kinski. But this documentary feels very much like a snapshot of the movie’s creation, rather than the full picture, and so is frustrating in its incompleteness.

This is a project that was certainly cursed from the beginning, and there’s something appropriate about the film’s subject being a man attempting to do something ludicrous and borderline insane – drag a ship over a mountain – because Herzog’s persistence can only be admired. From the get-go, there were issues with the natives, and the initial location had to be abandoned, with locals burning the camp to the ground as the crew pulled out. Burden also includes footage from the original version, which started filming over a year later with new locations, and starred Jason Robards as Fitzcarraldo, with (of all people) Mick Jagger as his sidekick. After five weeks shooting, almost half the movie was already in the can, when Robards came down with amoebic dysentery and had to return to the United States, where his doctor forbade him from returning. While Herzog tried desperately to find another lead, Jagger had to return to his Rolling Stones related duties, and his character ended up being written out entirely.

This is a project that was certainly cursed from the beginning, and there’s something appropriate about the film’s subject being a man attempting to do something ludicrous and borderline insane – drag a ship over a mountain – because Herzog’s persistence can only be admired. From the get-go, there were issues with the natives, and the initial location had to be abandoned, with locals burning the camp to the ground as the crew pulled out. Burden also includes footage from the original version, which started filming over a year later with new locations, and starred Jason Robards as Fitzcarraldo, with (of all people) Mick Jagger as his sidekick. After five weeks shooting, almost half the movie was already in the can, when Robards came down with amoebic dysentery and had to return to the United States, where his doctor forbade him from returning. While Herzog tried desperately to find another lead, Jagger had to return to his Rolling Stones related duties, and his character ended up being written out entirely.